The following is the text of a talk I gave at the University of Oregon Osher Center for Lifelong Learning on Dec. 10, 2014. My thanks to the Osher Center for the invitation.

Typically when we think of Spain we think of Andalucía: bullfights, flamenco, Moorish monuments such as the Alhambra, and so forth. Maybe we think of Barcelona, the Mediterranean, and the modernist architecture of Antonio Gaudí. Today I am pleased to talk to you about another corner of Spain, one that has very little to do with these images. Asturias is in central northern Spain, tucked in between the rugged Atlantic coast and the Cantabrian mountain range. It is a part of Spain that historically has been geographically isolated from the rest of the Peninsula, and for centuries it looked culturally toward the Atlantic, Brittany, and the British Isles. Together with its neighbor Galicia to the West, with its famed pilgrimage destination Santiago de Compostela, terminus of the Camino de Santiago or Road of Santiago, Asturias is the Spain on the so-called Celtic Rim. Culturally Asturias has much in common with Ireland and Wales. The local accent is a sort of brogue. The local alcoholic beverage of choice is sidra or cider, made from apples grown in local orchards for at least two thousand years. Asturian traditional architecture is decorated with symbols common to the Celtic world such as the trisquel or triple spiral, the hexapetala or hex, most frequently seen on granaries horreos in Asturian language), and traditional Asturian songs are accompanied by drum and gaita or bagpipe. In fact, Asturias may be the only place in the world where you can play castanets as you dance to a bagpipe.

Typically when we think of Spain we think of Andalucía: bullfights, flamenco, Moorish monuments such as the Alhambra, and so forth. Maybe we think of Barcelona, the Mediterranean, and the modernist architecture of Antonio Gaudí. Today I am pleased to talk to you about another corner of Spain, one that has very little to do with these images. Asturias is in central northern Spain, tucked in between the rugged Atlantic coast and the Cantabrian mountain range. It is a part of Spain that historically has been geographically isolated from the rest of the Peninsula, and for centuries it looked culturally toward the Atlantic, Brittany, and the British Isles. Together with its neighbor Galicia to the West, with its famed pilgrimage destination Santiago de Compostela, terminus of the Camino de Santiago or Road of Santiago, Asturias is the Spain on the so-called Celtic Rim. Culturally Asturias has much in common with Ireland and Wales. The local accent is a sort of brogue. The local alcoholic beverage of choice is sidra or cider, made from apples grown in local orchards for at least two thousand years. Asturian traditional architecture is decorated with symbols common to the Celtic world such as the trisquel or triple spiral, the hexapetala or hex, most frequently seen on granaries horreos in Asturian language), and traditional Asturian songs are accompanied by drum and gaita or bagpipe. In fact, Asturias may be the only place in the world where you can play castanets as you dance to a bagpipe.

yep

A very interesting aspect of this shared Celtic culture is the popular mythology. Some of the traditional supernatural beings in Asturian popular traditions are familiar to us from their insular counterparts we know from Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and Cornwall, in popularizing versions in school texts, films, and illustration traditions. The dragons, fairies, and satyrs of Celtic tradition are all here, as are the domestic tricksters (leprechauns), known as trasgus in Asturian, and the lord of the storms or ñuberu. These beings lived in the popular verbal arts of storytelling and song, and are rooted in specific communities and geographic locations, as we will discuss further on.

Asturias has the distinction within Spain of having the most robust popular mythological traditions in the country. By this I mean that there were and are more Asturians who were active participants in local folk traditions, more regional pride in these traditions, and regional institutions that promote the study of local mythological traditions in primary and secondary schools as well as at the university level. Other state agencies have followed suit. The Asturian tourism agency published a promotional video in 2004 that featured a friendly group of mythological beings flying around on the back of a dragon, while celebrating the birthday of the fairy, who was turning 20 that day. In this way, traditions that were more durable than their counterparts elsewhere in Europe have been repurposed in the contemporary construction of an Asturian regional identity, both internally, in schools and cultural activities, as well as externally, in tourism materials and other media directed toward national and international audiences.

Asturias, paraíso natural

Why have Asturian mythological traditions survived while their counterparts elsewhere in Spain and Portugal have not? Geography, mostly. As I mentioned before, Asturias is wedged between the Atlantic and the Cantabrian mountain range, which was all but impassable in the winter until the arrival of modern roadways. There are small fishing villages on the coast that were more easily accessed by boat than by land route, and mountain villages that were inaccessible during the winter months until the beginning of the twentieth century. This isolation prevented the intrusion of people and media from outside the region, and slowed the assimilation of Asturian language and culture to the Castilian majority culture of modern Spain. Also, the depressed economics of the region relative to other more affluent, industrialized areas of the North such as the Basque Country and Catalunya helped to shore up the survival of Asturian culture in the modern age.

intimate contact

Even within modern Asturias, folklorists report that non-industrialized populations are far more likely to have conserved local folk traditions. In particular, people whose daily life is centered on agricultural and pastoral rhythms are far more likely to be carriers of local traditions than those who work in mining or other industries. The daily intimate contact with nature, with the animal and human life cycle, and with the elements reinforces the meaning in traditional narratives that originally developed to give meaning to the relationship between humanity and nature. Noted Asturian ethnographer Alberto Álvarez Peña once commented that when we was in the field interviewing informants in the villages, typically a miner might know a handful of traditional stories, a farmer would have a more extensive repertoire, and a cowherd would have an impressive command of hundreds of traditional tales learned by memory.

Iglesia de la Santa Cruz, Cangas de Onís

The traditions we are about to discuss today all developed before the arrival of Christianity to the Iberian Peninsula, and indeed before the Romanization of the Peninsula. Before the importation of Roman Gods and later of the Christian God, these traditions served a purpose similar to that of the Roman gods and Christian saints that would come to replace them. That is, they were mediators between humans and their experience with the natural world, personifications of natural forces, and allies for humans whose power was to be respected and feared. For example, the spirit of a local river or lake, known in British tradition as a water fairy or pixie, was meant to allegorize the bivalent relationship between humans and water in nature. On the one hand, the river brings water and therefore life. It waters animals that we hunt and herd. It carries fish that we eat. But it can also kill by drowning or by contamination. The xana or fairy associated with a local river was therefore a way for humans to articulate this relationship with this aspect of nature. The xana is powerful but largely benevolent. She would often give villagers gifts of gold objects or money, but could also turn violent if provoked.

Many of the supernatural beings we will discuss here are similarly bivalent in nature: they can be benevolent but also represent the violence inherent in the natural world, over which we have little to no control. They were revered by Asturians and provided a framework for articulating one’s experiences with the local natural world. They served both as reference points and as explanations for our experience of the vicissitudes of nature.

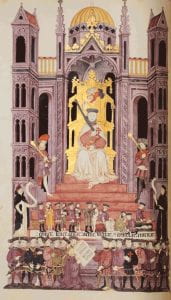

The arrival of Christianity transformed these traditions significantly. In Catholic society all spiritual authority must rest with God, Christ, Mary, the Saints, and the Church itself. The transition from Roman religion to Christianity was somewhat smoothed by the fact that Rome itself adopted Christianity. This institutional framework meant that Roman clerics would develop a transitional theology by which the Roman gods were mapped onto Christian saints, who for some time embodied both beings until such time as the identity of the Roman god merged and was assimilated to the Christian saint with whom he or she was paired. A similar process obtained in parts of the New World, when for example, Catholic saints were mapped onto the Yoruba Orixas in the Caribbean, or onto Aztec or Maya gods in Mexico and Central America. These syncretic practices are common in moments of transition or biconfessionalism in various historical moments.

However, the Asturian mythological beings did not fare well in the transition to Christianity. They were simply regarded by Catholic priests as heresies, and were pitted against the new religion. In this way, they were demonized and their positive meanings eroded. The spirits of nature that gave and took away became malevolent creatures who brought death and destruction only, and the cult of the old mythology and many other aspects of folk life were branded as heresy by the Church. As a result, a branch of narrative tradition emerges in the Christian period in which local priests are portrayed as locked in struggle with the local dragon or other being, in an allegory of the struggle between the old belief systems and Christianity. Priests and inquisitors inveighed against the old beliefs as Christian heresies, and associated mythological beings with negative figures in Christian tradition. In this way the busgosu or satyr, the spirit of the forest, becomes associated with the Christian Satan, who likewise is portrayed as having horns, the legs and hooves of an animal, and a tail.

remote geography helps

Given how relatively robust the Asturian mythological traditions are straight into the twentieth century, one has to wonder how robust Christianity itself was in the most isolated rural populations where these traditions thrived. Given that most descriptions of the spiritual life of such communities come to us from local priests, it is difficult to say to what extent they were believing Christians, and in particular what shape those beliefs may have taken. In the more remote mountain villages, mass is given only once a week by a priest who lives in the local town and rotates to the area villages. In one remote mountain village I visited, most locals were openly critical of the Church and reported that there were only two elderly women who regularly attended the weekly masses given by the local priest. This historical antipathy (or at least apathy) to the Church is certainly tied to modern politics as well. Asturias, and rural Asturias, was virulently anti-Franco, whose regime was aggressively and officially Catholic. As is well known, the Spanish Church was hardly a neutral party in the Spanish Civil War, during which the Church was hand in glove with Franco’s Fascists. This fact is not forgotten in rural Asturias, and the village in question, Sotres, in the Picos de Europa range, supported anti-Franco partisans for some twenty years after Franco took power.

Alberto Álvarez Peña

But modern politics is only partly to blame for the failure of Christianity to take root meaningfully in the lives of cowherds and other villagers in the remotest areas of Asturias. According to ethnographer Alberto Álvarez Peña, it is the rhythms of daily life, particularly of the shepherds and cowherds, that is responsible. These men and women spend long stretches of time in the heights above the villages pasturing their herds. Until the recent invention of motorized vehicles, many of them slept in the high pastures with their animals and only came down to the village in the late fall when the grass stopped growing. They were surrounded by nature, and it was the forces of nature that were the most immediate to them. They did not need an abstract, universal divinity such as Christ, or his priests, to explain to them how the world works and what their place in it was. They could observe these things every day in the changing of the seasons, which they experienced more fully than those in the village, and in the life cycles of the animals with whom they spent their days. Neither did they spend long enough in the villages or towns to be properly indoctrinated by the priests, who were in any event chronically understaffed. And due to Asturias’ very late and equally incomplete industrialization, these ways of life and the traditions they supported were able to survive well into the twentieth century, while industrialization and official national culture all but extinguished traditional mythological beliefs in the rest of the Iberian Peninsula.

What I’d like to do know is to talk about a few of the most well represented mythological traditions in Asturias. These are all local versions of beings you’ve probably heard about in other Celtic traditions. All of them have their roots in local geographies and beliefs, and all of them are metaphors for our experience living in nature.

La xana

image: Alberto Álvarez Peña

Perhaps the most well known being is the la xana (plural les xanes) or water fairy, who is associated with caves, grottos, rivers, and lakes. The xana is an almost entirely benevolent creature, human in appearance, who takes the shape of a very beautiful young woman with long hair dressed in traditional Asturian dress. The xana guards her treasures at the bottom of the lake, or in a cave, and is known to give humans gifts, usually skeins of golden yarn. In the center of Asturias she is represented as a Christian, probably by dint of her appearance, but in the East she is thought to be a Muslim, a spirit of the wives of the Muslim forces stationed in Asturias in the eighth century, abandoned by her husband when the Christians captured Asturias. Alternatively, depending on our understanding of the Asturian word moro, or Moor. It can mean either “Muslim,” as in the Muslim forces of the Umayyad Caliphate in Cordoba who occupied Asturias during the first half of the eighth century, or “pagan”, by distinction from “Christian.” This sense give the xana a more ancient origin, placing her at least in pre-Christian Roman times. In any event, like all these beings the xana is thought to be of ancient or pre-historic origin, or at the very least not subject to time as are ordinary humans. Some believe the xana to be a distant memory of a local pre-Christian goddess, which is true of most of the more powerful mythological beings we will discuss. They were once local gods, each of whom represented a different aspect of nature just as the Romans and Greeks had their gods of fertility, of the sea, of the hunt, and so forth. As local pagan institutions were replaced by Roman and then Christian cults, these traditions were unmoored from their traditional frameworks and set loose in the popular imagination. That is, without a class of priests, druids, or shamans to actively shape and interpret the cults of local gods, the locals who carried the traditions were freer to reinterpret and transform them as they liked. We see this tendency, one might call it a de-institutionalization of myth, in the development of many of these traditions.

el cuélebre

image: Alberto Álvarez Peña

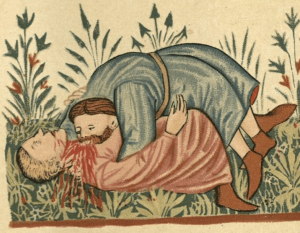

After the xana, el cuélebre, (male snake, in Spanish culebre) or dragon is probably the best-known member of the Asturian pantheon. This creature, similar to the dragons of Anglo-Celtic tradition, lives on the outskirts of a settled area in a cave, and is an enormous serpent with wings and legs. The cuélebre comes out of its lair to wreak havoc on the daily workings of the villagers, destroying farming or fishing equipment, poisoning wells and springs, and demanding the sacrifice of herd animals and eventually of human virgins this is where the image of the knight rescuing the dragon comes from. In pre-Christian times the dragon would have been a nature deity whose violent nature would have been placated by the sacrifice of herd animals, much like the Biblical Hebrew God who demanded the sacrifice of lambs and cows on certain days of the year in order to guarantee the balance between the interests of humans and of nature. In Christian times, the sacrifice of Christ made all others irrelevant and therefore heretical, and in order to demonize the old deity, Christians began turning the traditional sacrifices of animals into human sacrifices, which could more easily be denounced as a perversion of Christian doctrine and therefore a heresy. Christianization also brought innovations in the local traditions of cuélebres in which villagers, tired of the dragons’ destructive habits and taste for livestock or young girls, called in a local priest or in some cases a hermit to put an end to the creature or at least put the fear of god into him so he would no longer venture from his cave. One of the ways the cuélebre would terrorize villagers would be to block the local water source with his body and demand a ransom of herd animals or young virgins in order to unblock the source. This suggests its origins as a god of nature, similar to those South Pacific gods of volcanoes who require sacrifices in order to guarantee the volcano will not erupt. The cuélebre, like the volcano god, is a metaphor for the relationship between humans and nature.

Such gods or beings before Christianity were often benevolent. Another function of the cuélebre is also to guard treasure, and in pre-Christian times the cuélebre would also, like the xana, give presents to humans who sought him out in his lair, usually located in a cave in a mountain outside of a settled area. With Christianization, the cuélebre also became demonized and its generous aspect was suppressed, probably through its association with the Edenic serpent in Christian tradition. Curiously, in local traditions the cuélebre is always located in a cave into whose opening the sun shines on the day of the Summer solstice, meaning that the cuélebre is associated with the thinning of the veil between this world and the next. Other supernatural creatures traditionally appear on the Summer solstice, such as the xana, who appears in popular ballads on St. John’s night, combing herself with a golden comb.

pucker up

In one tradition, the xana enchants herself to become a cuélebre, and a human man must kiss her three times on the lips in order to turn her back into a xana, after which she rewards the human by marrying him and making him the head of a prestigious lineage. There are noble houses throughout Europe that tell such legends about their origins. These tales have their analogues in Greek legends about kings and heroes who are descended from the gods, and are a way to justify the feudal social order. That is, if one should ask why a given family deserves to rule over all the others, the answer is simple: we are descended from gods, and you are not! There is a vestigial version of this tradition in the tale of the princess and the frog, in which the princess must kiss a frog in order to break the enchantment and change the frog back into a prince. The movie franchise Shrek turned this tradition on its head by having the princess’ true nature be monstrous, while the enchantment turned her into a beautiful young human woman.

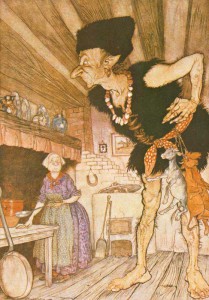

Oviedo resident dressed as a busgosu, Antroxu (Carnaval) 2013

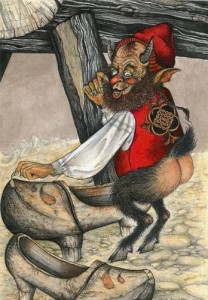

Another creature that lives in the forest and is known to wreak havoc on the lives of nearby villagers is el busgosu or satyr. The busgosu is the half-man, half-goat Lord of the forest, whose job is to protect the interests of the forest and regulate the relationship of humans with natural forces within it. He is an Asturian version of the Greek god Pan, who is also represented as half-goat and half-man, with horns, cloven hooves, and a tail. Legends of the busgosu represent him as alternatively malevolent and benevolent. At times he helps shepherds who are lost in the wood and offers to repair their huts in bad weather. At other times he is more of a boogeyman who harasses or kills villagers lost in the wood. It is noteworthy here to point out the key difference in these two versions. In the former, positive version is told among shepherds, who spend the majority of their time away from town and are the least catechized population (and therefore the most likely to experience these beings as forces of nature rather than of evil). In Christian times, the busgosu became demonized, and it is no accident that modern representations of the Devil show us a half-man, half-goat, with horns and a tail. Again, there is no room in the Christian cosmovision for competing gods, and so these gods must be demoted to demons or in the case of the busgosu, the Devil himself. We see vestiges of the idea of the busgosu and related beings as gods in Asturian traditions about the Devil or Demons giving humans important technologies. In one tradition the Devil gives humans the saw, which enables them to cut down trees and build homes. In another the Devil builds humans bridges over local rivers. These traditions are confused by the traditional beings’ more recent identity as devilish. It doesn’t make sense for the Devil to be building bridges and donating new technologies. But it does make sense for a nature god, who is sometimes dangerous but not benevolent per se to donate technologies to his obedient followers. The metaphor is clear: you may proceed with the business of developing your civilization only to the extent that you are respectful of nature. Under Christianity this metaphor is broken, and what is left is a strange idea that very basic technologies such as the saw and the bridge for some reason come from the devil. There are a number of such traditions that attribute supernatural origins to ancient ruins and artifacts whose human origins have been lost to local memory. Ruins of ancient dolmens and other Neolithic structures are said to have been built by a race of demigods or titans known as moros, or Moors, not because they were Muslim but because they were not Christian. Roman nails and other iron or stone implements that surface in fields are likewise attributed to activities of dragons or lightning strikes caused by an angry weather god, the ñuberu.

El ñuberu

image: Alberto Álvarez Peña

This last nature-related being, the ñuberu or ‘master of the clouds,’ from the Asturian word for cloud ‘ñube,’ is most clearly related to forces of nature, and it may be that it has survived as such because it rains so darn much in Asturias. The first time we were there we arrived in January 2013 and left in June 2013. I am not exaggerating when I say it rained for about 170 of those 180 days. They tell me it was uncharacteristic, but as I have yet to spend another winter season in Asturias I have no basis for comparison. Therefore it is not surprising that the traditions about the ñuberu have been so faithfully transmitted. The ñuberu is represented as an older man, bearded, wearing a wide-brimmed hat, dressed in animal skins and rags. He keeps to the heights where he can survey his works, or rides around the skies on winds and clouds. He is thought to be the latter-day descendent of the Celtic god of rain and lightning, Taranis, whose lends his name to several toponyms in Asturias and Galicia, such as the towns Tarañes, Táranu, Taraña, and the tautological Tarañosdiós.

I smell a ‘cristanuzu’

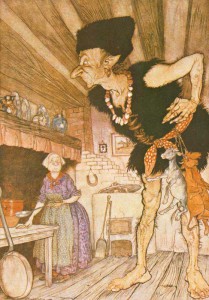

Illustration by Arthur Rackham, 1918, in English Fairy Tales by Flora Annie Steel (source: Wikipedia)

Occasionally he falls to earth taking on the name Xuan Cabrita literally ‘John Little Goat’ but with the sense of ‘Jack Frost.’ In one tradition from the town of Artidiellu, they say that one day a lightning bolt struck and killed a cow, and a ñuberu fell to earth with the lightning. He was a short, ugly, hairy man. He ran into two shepherd boys who took him in and shared their food with him. In the morning he asked them to make a fire using green wood. As the fire grew and gave off thick smoke, he climbed the smoke up to the sky. Before he left, he said to the shepherds: “If you go to the city of Brita ask for Juan Cabrita.” Years later one of the shepherds, now grown, was traveling on a boat and was shipwrecked. He clung to a piece of wood and eventually washed ashore in a strange land. He wandered for a time, living on the charity of strangers until he eventually came to a town named Brita. Then he remembered what the Nuberu had said years ago and asked to see the house of Xuan Cabrita. He knocked on the door, and Xuan Cabrita’s wife answered him, telling him that her husband was out on a trip and would be back later. She asked him to come in and hid him in a dark room filled with smoke. When her husband the Nuberu came home later that night, she said that he smelled a ‘cristianuzu’ — a Christian (probably meaning ‘human’)— but his wife told him it was a man from Lligüeria whom he had met in Canga Xuangayu. Then Xuan Cabrita said: “Cor! That man is a friend of mine! Don’t kill him!”He sat down with the young man to have dinner with him and they spent the evening talking. When Xuan Cabrita asked him where he was from, Xuan said that he happened to be coming from Lligüeria de drop a hail cloud and there he had heard that the wife of the young man, due to his prolonged absence, thought him was dead and was planning to remarry. The young man was very worried because he could not stop the wedding from happening, being so far away from home, but Xuan Cabrita put his mind at ease: he promised to fly him there on the winds. He gave him a sharp stick and said he should spur him on with it, saying “arre demoniu, arre demoniu” (giddiyup, demon), but that he should not call out to either God or the Saints because then Xuan Cabrita would let him fall to earth. Flying through the air they quickly came to Lligüeria. It was already morning, and they had arrived just in time to get to the church to stop the wedding. In that moment the young man exclaimed: “Oh God, I can see my town!” In that instant the Nuberu gave such a shudder that the young man fell to earth. He was lucky: he landed and caught on a tree branch next to the church and suffered only some scratches, and managed to stop the wedding in time.

make it to the church on time

Iglesia San Esteban (Aramil)

source: turismoasturias.es

As in other traditions that allegorize the ups and downs of humans’ relationship with nature, Xuan Cabrita here repays a favor to the man, whose respect for the spirit of the winds pays off down the road. Like his counterparts the xana and the cuélebre who give humans golden treasures, or other creatures who grant technology such as bridges and saws, the Nuberu giveth and the Nuberu taketh away.

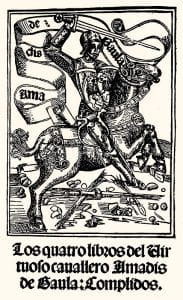

He is known by other names throughout Asturias. He is said to live in different cities: Tudela (in Navarra), Brita, Oritu, el Grito or Exitu (Asturian for Egypt). This last case is curious: why would a local nature spirit in Asturias come from Egypt? As it turns out, in the nineteenth century when many of these tales were collected was the golden age of European orientalism. Collections of Eastern tales, fables, and traditions were widely available, and as a result some local traditions began to borrow Eastern settings in order to appeal to current literary tastes. We often think of folk traditions as being somehow hermetically sealed off from printed literary tradition. We exoticize the rural informants as being quaintly pre-industrial and perhaps pre-literate. While it is true that general literacy rates in rural Asturias were quite low even by European standards until relatively recently, there is a high degree of interpenetration between written and oral traditions that goes back centuries, at least to the early age of print in the sixteenth century and possibly before this time, as written traditions were disseminated to audiences in public readings of manuscripts and later printed books, once a common form of popular entertainment.

el trasgu

image: Alberto Álvarez Peña

The trasgu or trasno is the Asturian equivalent of the leprechaun, a mischievous domestic creature who causes minor annoyance and disorder but who ultimately is relatively harmless. In Asturian tradition he is described as wearing a red cap, and curiously, as having a hole through his left hand. The trasgu disrupts the rhythms of household and work life by stealing small objects such as keys, moving furniture during the night, and generally making a nuisance of himself. In some places it is told that the trasgu can be domesticated, after which he will perform chores around the house until he is released from servitude. This aspect of the Celtic tradition has survived in J.K. Rowling’s house elves, who are bound to serve the households of wizards until they are presented with an item of clothing to wear. Anyone who remembers Dobby the house elf from the Harry Potter books or movies will be familiar with this variant tradition. The trasgu, like the Gremlin from Anglo tradition, is a metaphor for the normal disorder that invades our lives, a reminder that despite our best efforts, some things will never be completely organized or regularized. They are margin of error incarnate. Appropriately, when young children create mischief their elders scold them calling them pequeñus tragsus. This comparison makes a lot of sense when we take into account the trasgu‘s behavior. He is annoying to the point of enraging, but ultimately benevolent, and even lovable. In one tradition, a local family is so fed up with the shenanigans of their house’s trasgu that they pack up and leave. Once their cart is packed up and ready to pull away, the trasgu pops his head from under the bundles and says: ya que vais tous, de casa mudada, tamién múdome you, cula mióu gorra culurada, or in English since you’re all moving away from this house, I’m moving too, with my little red hat!

In another version of this scenario, the family is all packed and realizes they left a bundle of corn in the house. They send the youngest son back in to fetch it, who runs into the trasgu at the door, who is coming out carrying the corn, and says: tranquilos, que llévola yo, ‘don’t worry, I’m bringing it,’ then hops onto the cart to follow the family to their next house. The moral of the story: a certain amount of domestic chaos and disorder is inevitable, and like the forces of nature needs to be respected in order that you carry on with your life.

el diañu burllón

image: Alberto Álvarez Peña

Other manifestations of the trasgu are more malevolent and come to be associated with the devil or his minions. The diañu or diañu burllón is a Christian concept, and grafts onto the domestic trasgu the horns and goat-legs used to represent Devils and Demons in Christian tradition. Some of these versions are able to take the shape of goats and other animals, and their mischievous exploits turn violent and are not limited to the domestic sphere. The Christianization of the trasgu and other related traditions turns them all into minor demons, blurring their pre-Christian characteristics and painting them all with the same demonic brush.

Nonetheless, the trasgu is one of the most beloved mythological figures in modern day Asturias. Restaurants and other business use him in their names and signage. trasgu fartu Around the corner from our apartment in Oviedo there was a sidrería, a restaurant that serves the local natural cider and traditional foods from the region, called El Trasgu Tartu or the Sated Trasgu. trasgu cerrajeros Around the corner from this there was a locksmith named trasgu, in honor of the propensity of those creatures to steal one’s keys. So while the primary oral traditions collected by ethnographers have mostly died out, there is a secondary life to these traditions that is symbolic of regional culture and identity. xana restaurante Likewise the Xana is found in name of businesses and organizations throughout Asturias, such as this restaurant, a brand of local beer, and a beauty shop, vacation apartments, and others.

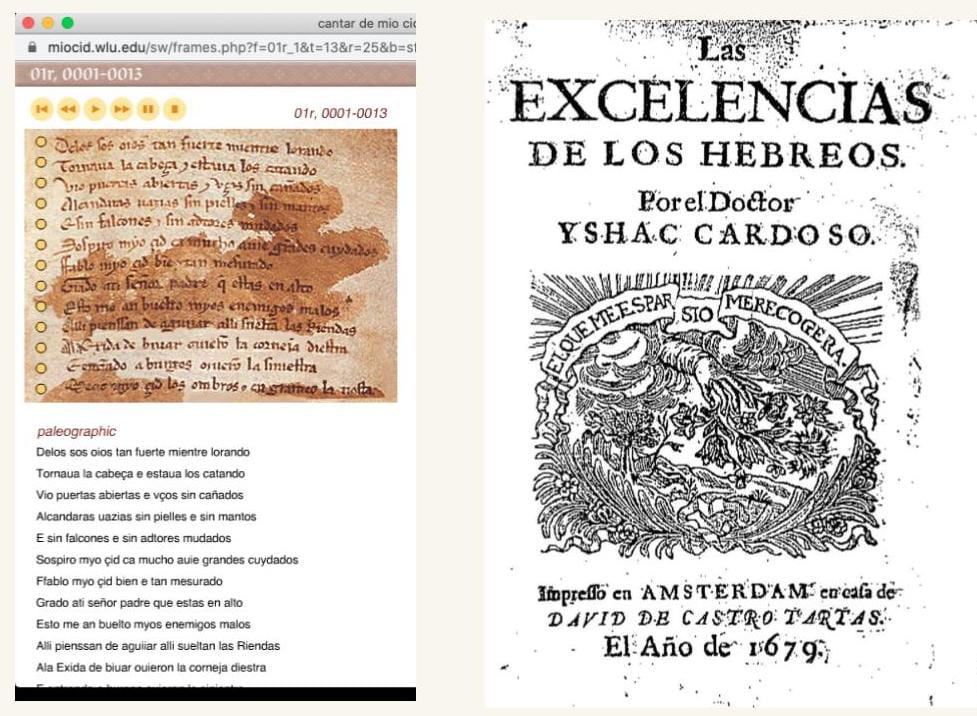

So it is clear from these contemporary examples that today’s Asturians still value these mythological traditions in some way, even if they themselves are not carriers of the traditions as repositories of knowledge and of transmitters who tell tales and stories and teach them to their children. The question is, do they —did they— believe in these creatures? This is a difficult question. When we ask if someone believes in God, we have a common reference point. We usually know what it looks like and sounds like if someone believes in God. But what does it mean to believe in a mythological creature such as a cuélebre or a xana. We can go to several sources for answers. The first is history. When these traditions emerged before Christianity, we can assume they were gods of a pagan religion and that people believed they existed in a concrete sense. In fact, according to one theory, in Neolithic times, humans actually hallucinated the voices of their idols or gods directly in their heads, so their experience was quite direct. There was no question as to belief when you saw the idol and heard the voice of the god every day. Let’s assume this was the case some five thousand years ago in Asturias. Then eventually, as human cognition and society advances, the gods stop talking to you directly and recede, in this case into the forests, caves, and rivers, where they appear sporadically, often on solstice days or other points on the agricultural cycle with which they are associated. At this point the legends and myths, which were quite unnecessary in the days when the gods spoke to you directly, begin to develop, in order to maintain a collective consciousness of their power and their value as metaphors for human experience in nature. This is where we can probably speak of belief in ways that are recognizable to us from our own experience as moderns. Then there is a long, probably very long transitional period in two parts. In the first, the local gods are in competition with Roman gods, and begin to take on aspects of Roman representations of their counterparts from Greek and Roman religion. Finally, with the advent of Christianity to the Peninsula, which we must remember proceeded from East to West and from South to North, would have arrived late to Asturias, which was home to some Roman settlements but whose geography made it possible for large rural populations to avoid Romanization and Christianization practically altogether.

So it is clear from these contemporary examples that today’s Asturians still value these mythological traditions in some way, even if they themselves are not carriers of the traditions as repositories of knowledge and of transmitters who tell tales and stories and teach them to their children. The question is, do they —did they— believe in these creatures? This is a difficult question. When we ask if someone believes in God, we have a common reference point. We usually know what it looks like and sounds like if someone believes in God. But what does it mean to believe in a mythological creature such as a cuélebre or a xana. We can go to several sources for answers. The first is history. When these traditions emerged before Christianity, we can assume they were gods of a pagan religion and that people believed they existed in a concrete sense. In fact, according to one theory, in Neolithic times, humans actually hallucinated the voices of their idols or gods directly in their heads, so their experience was quite direct. There was no question as to belief when you saw the idol and heard the voice of the god every day. Let’s assume this was the case some five thousand years ago in Asturias. Then eventually, as human cognition and society advances, the gods stop talking to you directly and recede, in this case into the forests, caves, and rivers, where they appear sporadically, often on solstice days or other points on the agricultural cycle with which they are associated. At this point the legends and myths, which were quite unnecessary in the days when the gods spoke to you directly, begin to develop, in order to maintain a collective consciousness of their power and their value as metaphors for human experience in nature. This is where we can probably speak of belief in ways that are recognizable to us from our own experience as moderns. Then there is a long, probably very long transitional period in two parts. In the first, the local gods are in competition with Roman gods, and begin to take on aspects of Roman representations of their counterparts from Greek and Roman religion. Finally, with the advent of Christianity to the Peninsula, which we must remember proceeded from East to West and from South to North, would have arrived late to Asturias, which was home to some Roman settlements but whose geography made it possible for large rural populations to avoid Romanization and Christianization practically altogether.

We have mentioned the effect of Christianity on the old gods or beings. They were demonized in Christian sources. Parish priests inveighed against the old beliefs in order to safeguard the souls of their congregants. They read a steady stream of anti-pagan treatises that condemned as heretics the practitioners of folk traditions, be they medicinal, pagan rite, or cults of local gods such as the beings we have been discussing. The communities became biconfessional. Some professed Christianity, some stayed with the old pagan beliefs, but I would say that a substantial majority practiced some combination of both. For example, an informant once told the ethnographer Alberto Álvarez Peña that in her village there were seven churches, and each church has its own Virgin Mary. The seven virgins, according to the woman, were sisters, and spoke to one another, and she went on to describe the private life of these local goddesses in detail. This can only be understood as the survival of a pagan mentality some fifteen hundred years after the Christianization of Spain.

But what about the traditional beings themselves, the xanas and cuélebres of the old beliefs? Did people believe in them in recent times? And what do we mean by believe? This is a complex question that we cannot possibly answer in five minutes. After Christianity had gained a firm foothold in the region, modern scientific beliefs —and they are beliefs, do not be fooled— came to challenge both the old beliefs and Christianity to boot. In this phase the old gods retreated further. First they had retreated from the minds of the people to the woods. Then they had to do battle —quite literally, in some traditions— with Priests and Saints, who almost finished them off. Now they really had the rug pulled out from under them in the modern era. Humans were demonstrating their dominance over nature in ways that were unimaginable before the eighteenth century. Mines probed deeper into the earth, ships were able to move cargo further and faster and in worse conditions than ever, and the airplane took us into the sky where, if indeed he still lived there, we could look eye to eye with the nuberu himself. Now what? Some informants provide clues as to how the traditions adapt themselves to the new conditions of human consciousness. The gods retreat further, into the past, but still retain their authenticity. In recent years an informant is asked about a local cuélebre, and he replies that when his grandfather was a boy, there was a cuélebre in a cave on a local hillside that used to appear once in a while, but he doesn’t come out anymore. Note that he didn’t say, as informants often do when relaying traditions in which they do not believe in the strict sense of the word, ‘nobody believes in that dragon anymore.’ Rather, he respected the authenticity of the tradition, authorizing it for further transmission. He brought the cuélebre in line with modern, science-believing tradition by not requiring it to be tested current ideas about the relationship between nature and humanity. He puts the burden of proof on past generations, who are no longer present to speak. This a continuation of the trajectory of the old gods, who went from speaking in our heads, to receding into the forest or the sky, to disappearing altogether and existing as a tradition that no longer shapes everyday action or thought but that occupies its place in popular belief alongside Christianity and modern science.

I hope that these brief comments have been thought provoking, and that you have nuanced your understanding of Spanish culture, and European culture in general. My sources for the mythological material where two books by Alberto Álvarez Peña published in Spanish, the one is titled Mitología asturiana and the other Mitos y leyendas asturianas. The theory of Neolithic humans hallucinating the voices of their gods is from The Origin of Human Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, by Julian Jaynes.

Then COVID happened. The program was canceled, and the reader, which I’d spent so many hours preparing, was suddenly useless, at least for 2020. Hopefully I’ll use it in 2022.

Then COVID happened. The program was canceled, and the reader, which I’d spent so many hours preparing, was suddenly useless, at least for 2020. Hopefully I’ll use it in 2022.

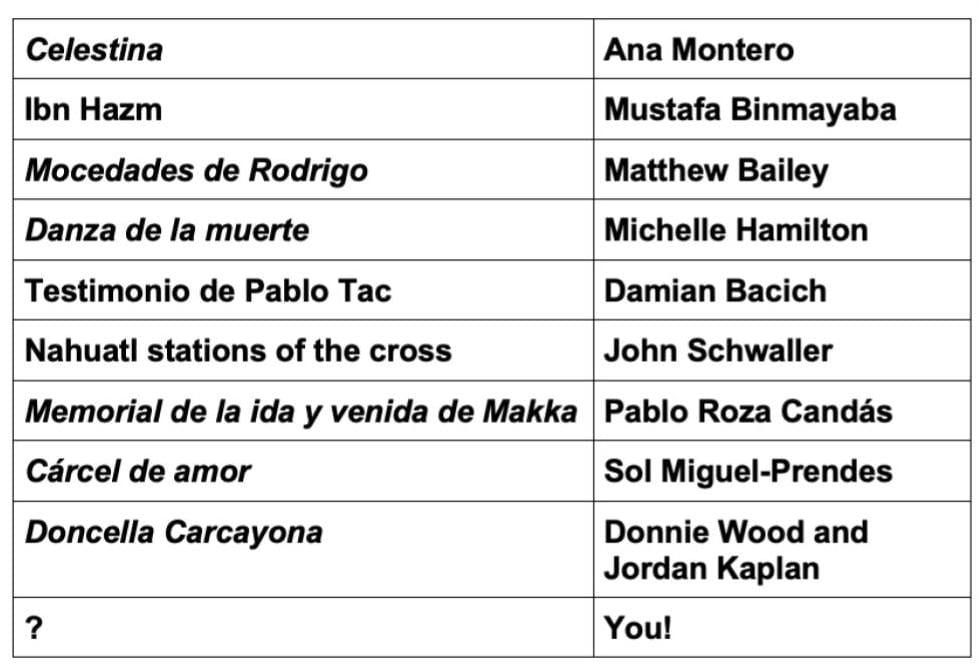

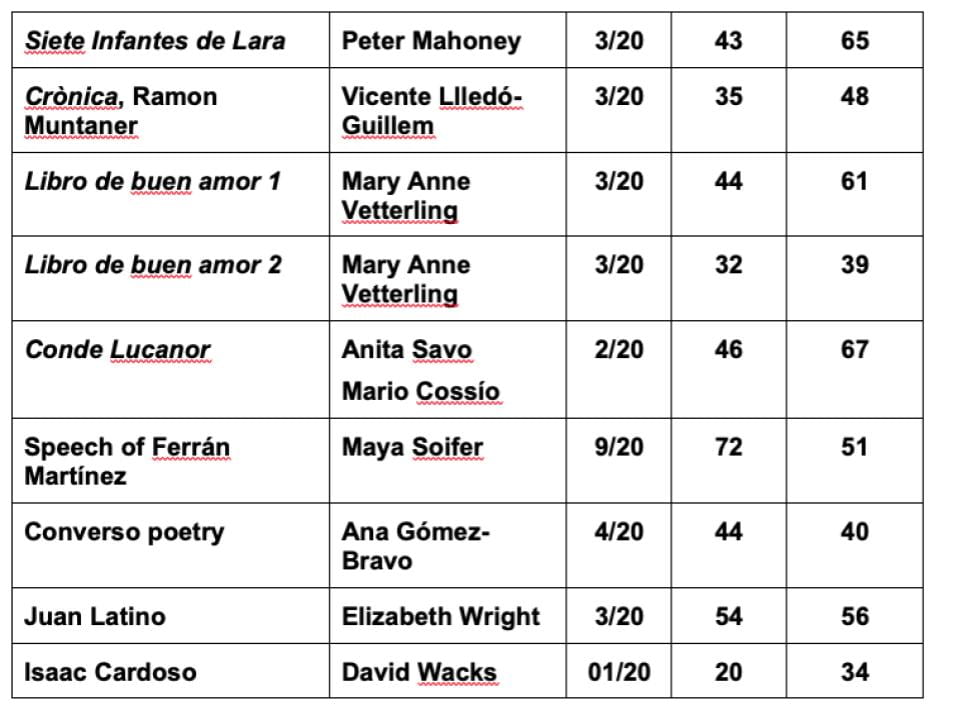

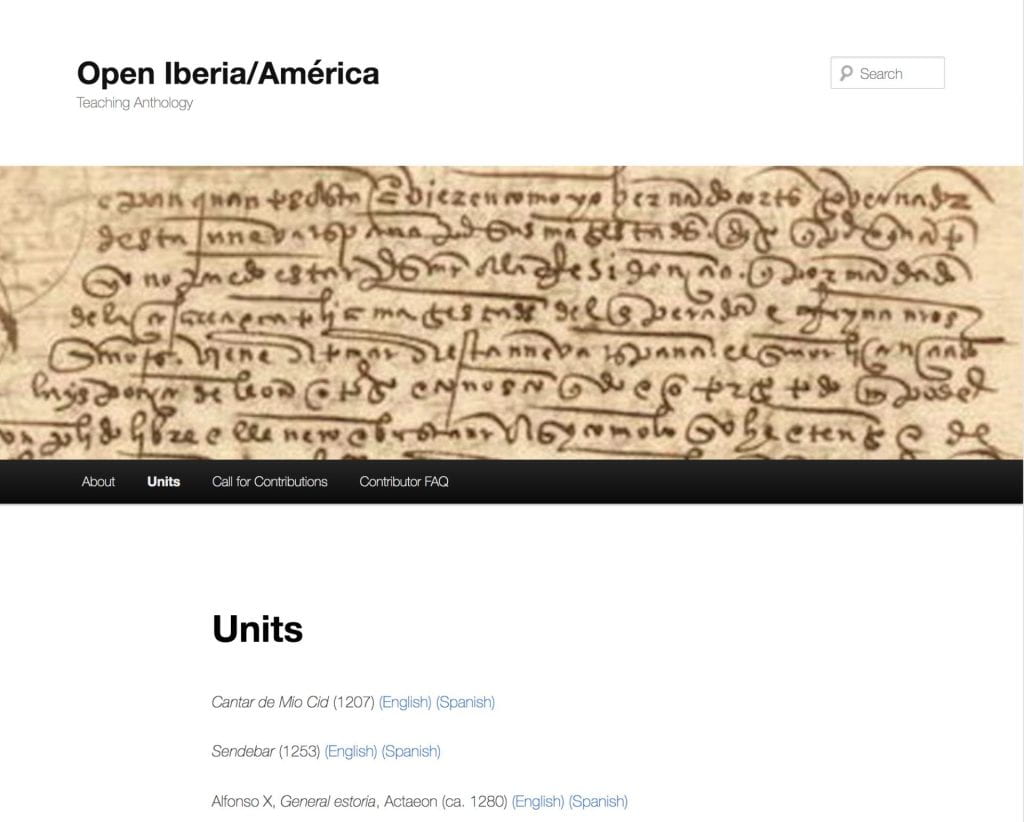

Anyone who has taught panoramic survey courses of literature knows the frustration of working with published textbooks. I’ve argued both sides of the question in my blog:

Anyone who has taught panoramic survey courses of literature knows the frustration of working with published textbooks. I’ve argued both sides of the question in my blog: