Gomes Eanes de Azurara, Crónica dos feitos da Guiné (BNF Port 41 f. 1r)

Modern capitalism has its origins in the institution of chattel slavery, in particular the enslavement of Black Africans. As we know, all institutions require complicated symbolic systems to legitimate them and reinforce their power in society. Enslavers attempt to justify and support their actions with robust symbolic systems. One of the ways in which Europeans justified the enslavement of Black Africans was the Curse of Ham, or the idea that Black Africans are descended from Ham, who was cursed among his brothers for not covering his father’s nudity, and for not abstaining from sex with his wife while sheltering on the ark for forty days. In order for this Biblical legend to justify the enslavement of Black Africans, two things have to happen. First, Ham must be identified with Black Africans, and second, actual Black Africans must be identified as slaves.

Scholars frequently cite the Chronicle of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea, by Gomes Eanes de Azurara, written in 1453, as the first documented example of these ideas coming together as a justification of Early Modern slavery. In it, Azurara identifies Black Africans living in Guinea as the descendants of Ham, whose slavery is a result of the Biblical Curse of Ham:

And here you must note that these Blacks, given that they are Muslims like the others, are in any event the slaves of the latter by ancient custom, which I believe to be because of the curse that Noah cast upon his son Ham after the flood, by which he cursed him, that his generation be made subject to all the others of the world.

E aquí haveis de notar que estes negros, posto que sejam mouros como os outros, são porém servos daqueles por antigo costume, o qual creio que seja por causa da maldição que depois do dilúvio lançou Noé sobre seu filho Cã, pela qual o maldisse, que sua geraçao fosse sujeita a todalas outras do mundo… (Zurara 85; Tinhorão 51)

Azurara links the two curses of Ham: (1) Blackness and (2) Slavery in what is considered a pivotal moment for the theory of race in Europe, one shaped by the incipient Portuguese slave trade. This ideological turn is one of the ideas that unlocks the possibility of modern chattel slavery and consequently the development of modern capitalist world systems, so it is worth drilling down a bit into the ideological landscape of race and of interpretations of the story of the sons of Noah and in particular, the curse of Ham.

What is the genealogy of this idea on the Iberian Peninsula? How do we get from the Biblical Ham to the beginnings of Biblical justifications of slavery in the Early Modern period that were shaped by and in turn reinforced the transatlantic slave trade?

We’ll begin with the text in the Hebrew Bible, then trace the development of the Curse of Ham in medieval sources, focusing on Iberian writers and artists.

The question of the geographical distribution of the sons of Noah and their relative skin tones is post-biblical. The Biblical Curse of Ham deals strictly with enslavement. As a punishment for his disrespect and disobedience, the descendants of Ham (through his son Canaan) are cursed to be slaves to the descendants of Shem and Japheth:

May God enlarge Japheth,

And let him dwell in the tents of Shem;

And let Canaan be a slave to them. (Gen 9:20-29)

It’s clear to see how this story was used in the Biblical context to justify the Israelite subjugation of the Canaanites in their conquest of the Promised Land, but less so how it came to justify the enslavement of Black Africans. For this, two things need to happen: First: Ham needs to be Black. Second, Blackness needs to be associated with slavery.

How does Ham become black?

The idea develops over time. In sources from antiquity there is no clear link between skin color and slavery. Late antique Rabbinic traditions such as those of R. Huna and R. Joseph (fourth century) in Genesis Rabbah distinguish between blackness on the one hand, and slavery on the other, but do not conflate the two (Goldenberg, Curse 168). In his study of the Curse of Ham in Jewish tradition, David Goldenberg argues that over time, as slavery in the Mediterranean began to be associated increasingly with Black Africans, Ham’s twin curses of Blackness and slavery became more common (Goldenberg, Curse 174).

Medieval Jewish and Islamic traditions attribute the blackness of Ham’s descendants as God’s punishment for his disobedience and sexual incontinence, two characteristics stereotypically attributed to Black Africans by white supremacist pseudo-science. According to these traditions, although Noah and Noah’s sons were commanded to abstain from sex with their wives during their time on the ark, Ham and his wife ignored the ban and as a punishment God turned Ham’s semen black, which would ensure that his son Canaan, and in turn all of Canaan’s children, would be born Black. This is repeated in a number of influential sources known to Iberian authors, who in turn introduce their own innovations to the legend.

The Muslim commentator Ibn Mutarrif Al-Tarafi, writing in Sevilla in the eleventh century, repeats the tradition that Ham’s semen turned black as a punishment for disobeying God on the Ark, but changes Ham’s crime from having sex with her during a period of mandated abstinence to beating her, swapping out sexual incontinence for domestic violence as supposed characteristics of Black Africans:

Qatada relates that there were only eight people on the Ark: Noah, his wife, his three sons Shem, Ham, and Japeth; Ham hit his wife on the Ark and for this reason Noah asked God to turn his seed black, and that is the origin of the Blacks (al-Tarafi 69)

Another variation of the legend found in the Talmud that circulated in the Iberian Peninsula states that there were three of the ark’s passengers who were cursed for violating the abstinence order: the dog, the crow, and Ham. The dog’s punishment was to remain attached to his partner after coitus, the crow’s was to spit during coitus, and Ham’s was for his seed and therefore his descdendants to turn Black (Goldenberg, Black and Slave 52). The first Western Latin reference is found in the 1245 Extractiones de Talmut, a Latin translation of key passages of the Talmud meant to serve as a resource for anti-Jewish polemicists. Luis Girón-Negrón observes some fifty years later, this legend makes its way into the Libro del Cavallero Zifar. Interestingly, here the author conflates the name Ham (Cam) with that of the dog (can) (Wagner 37; Girón-Negrón 284).

Noahic geographies and race

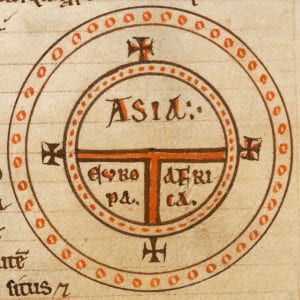

T-O Map Etymologiae 12th c. British Library, Royal 12 F. IV, f.135v

Later medieval copies of Isidore of Seville’s 7th-century Etymologies feature maps that associate the continents with the sons of Noah: Japeth with Europe, Shem with Asia, and Ham with Africa, and Medieval Arabic sources typically associate Ham with contemporary Black Africans. The influential Persian historian Al-Tabari (9th c), whose work is widely cited in al-Andalus, confirms this tradition in his History that Ham’s son Canaan is the progenitor of the “Blacks, Nubians, Fezzan, Zanj, Zaghawah, and all the peoples of the Sudan” (al-Tabari 2: 11).

Christian sources, some of which draw at least partially on Arabic geographers, likewise bring different agendas to bear on the legend. Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada, in his De Rebus Hispaniae, composed around 1250, notes that the sons of Ham occupy Africa, but reserves part of Asia, normally apportioned to Shem, to the sons of Japhet. His comment “that which the sons of Ham and Japhet possessed in Asia was by way of war.” This is a reference to Crusade, for he also details that the sons of Japhet also possessed the “mountains Amano and Toro, of Cilicia and Siria, that are in Asia, and all of Europe to Cádiz of Hercules, at the farthest reaches of Spain” (Jiménez de Rada 62). Cádiz was at the time still under Muslim rule, and would be for another decade, and the Crusader siege of Antioch was in 1098, but grew to great symbolic prominence as a model for holy war on the Peninsula.

Taurus and Nur Mountains source: Google Maps

The compilers of Alfonso X’s universal history, the General estoria, begun in the late thirteenth century and completed during the reign of Alfonso’s son Sancho IV in the early fourteenth, further develop the Noahid legacy in the context of military and political struggle between Christians and Muslims on the Iberian Peninsula:

Whereas, anyone who wishes to know from where this great and longstanding enmity between Christians and Muslims may here see the reason; for the Gentiles and Christians that are alive today come primarily from Shem and Japhet, who populated Asia and Europe. Yet still, despite the fact that some of the descendants of Ham have become Christian, either by preaching or forcefully as prisoners or slaves. And the Muslims come principally from Ham, who populated Africa, but there are some of them descended from Shem or Japhet, who by the false preaching of Muhammad become Muslims, whereby we have, according to this right and privilege that our father Noah granted to the descendants of Shem and Japheth, that wherever the Muslims may be in whichever other lands, that because they are Muslims, are all from Ham, and if we might take from them their property through combat or by any type of force, and even capture them and make them our slaves, that we commit no sin or error in so doing. And should we cease to fight them it should only be out of our better judgment or if by chance we are not prepared because of their greater numbers… (Alfonso X 1: 91)

Here the compilers of the GE build on Jiménez de Rada’s crusader geography with a bit of crusader theology, reinforcing the bulls of crusade that supported military efforts against Islam first in the Iberian Peninsula and later in the Eastern Crusades. Still, there is no reference to Blackness per se, only to the association of Muslims with Africa.

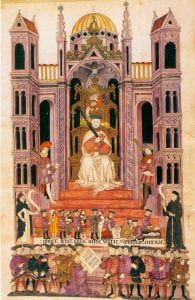

Banquet of Balthazar, Alba Bible (source: Wikipedia)

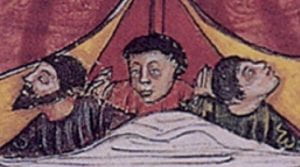

It is not until the Biblia de Alba, compiled over a century after the General estoria, but still some years before Azurara’s chronicle, where we see one of the first explicit links between Ham, Blackness, and slavery. Completed in 1433, some twenty years before Azurara’s Chronicle of Guinea, The Biblia de Alba or Biblia de Arragel was a collaboration between Rabbi Moshe Arragel and an anonymous Christian cleric or clerics and is unique in its ecumenical approach to combining Christian and Jewish commentaries on the Torah.[1] In any event, Arragel equates the offspring of Ham’s son Canaan with the Muslim Black Africans of his own day. He writes: “And Canaan was a a slave of slaves, and some say that they are the Black Muslims, who are slaves wherever they be” (“E Chanaan fue siervo de siervos. Algunos dizen que son los moros negros, que do quier que cativos son”) (Paz y Meliá f. 33r; Goldenberg, Black and Slave 108 n 7). The miniature that illustrates this passage (below) depicts Ham with stereotypically Black African features, and is the first such depiction of Ham I was able to identify.

MS Alba Bible f 33r. Courtesy Fundación Casa de Alba (Goldenberg 111)

These examples together form a fairly clear trajectory of a theory of race used to justify the enslavement of Black Africans. Just as soon as Iberians began the exploration of West Africa and began to develop what would in the space of decades become a full blown global slave trade, Iberian writers expanded on previous uses of the Curse of Ham to identify Black Africans as the descendants of Ham bearing the curse of enslavement, and to locate these Black Africans in actual time and space building on existing geographic traditions and by the time of Azurara, on actual Black bodies in real time.

Works Cited

- al-Tarafi, Abu Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Mutarrif al-Kinani. Storie dei profeti. Translated by Roberto Tottoli, Il melangolo, 1997.

- Alfonso X. General estoria. Edited by Borja Sánchez-Prieto, Fundación José Antonio de Castro, 2009.

- al-Tabari. The History of Al-Tabari: An Annotated Translation. Translated by Franz Rosenthal, vol. 1, SUNY Press, 1989.

- Carasik, Michael, editor. The Commentator’s Bible: Genesis. Translated by Michael Carasik, Jewish Publication Society, 2018.

- Girón-Negrón, Luis M. “La Maldición Del Can: La Polémica Antijudía En El Libro Del Caballero Zifar.” Bulletin of Hispanic Studies (Liverpool), vol. 78, no. 3, 2001, pp. 275–95.

- Goldenberg, David M. Black and Slave: The Origins and History of the Curse of Ham. de Gruyter, 2017.

- —. The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Jiménez de Rada, Rodrigo. Historia de los hechos de España (De Rebus Hispaniae). Translated by Juan Fernández Valverde, Alianza Editorial, 1989.

- Jordão, Levy Maria, editor. Bullarium patronatus Portugalliae regum in ecclesiis Africae, Asiae atque Oceaniae: bullas, brevia, epistolas, decreta actaque Sanctae Sedis ab Alexandro III ad hoc usque tempus amplectens. Ex Typographia nationali, 1868.

- Paz y Meliá, Antonio. Biblia de Alba. 1899.

- Phillips, William D., Jr. Slavery in Medieval and Early Modern Iberia. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

- Tinhorão, José Ramos. Os negros em Portugal: uma presença silenciosa. 3a edição., Caminho, 2019.

- Wagner, Charles Philip, editor. El libro del cavallero Zifar (El libro del Cauallero de Dios). University of Michigan, 1929.

- Williams, John. “Isidore, Orosius, and the Beatus Map.” Imago Mundi, vol. 49, 1997, pp. 7–32.

- Zurara, Gomes Eanes de. Crónica da Guiné. Edited by José Bragança, Livraria Civilização Editora, 1973.

This post is a version of a paper given at the 2021 MLA for the New Currents in Medieval Iberian Studies panel. Thanks very much to presider Simone Pinet.

Fascinating blog post, David. One question: was the 11th C Iberian theory articulated by Ibn Mutarrif Al-Tarafi accompanied by the actual enslavement of sub-Saharan black Africans in al-Andalus? Relatedly, was there any acceleration of African enslavement under the Almoravids?

Great question! I didn’t research much into slavery in al-Andalus for this paper so I cannot answer it, sadly. I’ll find out!