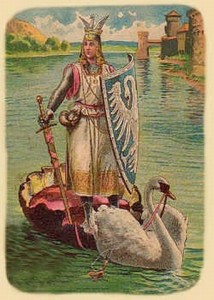

The Knight of the Swan was the legendary ancestor of French crusader Godfrey de Bouillon. Source: Wikipedia

Chivalric novels with crusading themes were extremely popular in Western Europe in the late middle ages. French authors in the twelfth century produced literary prose versions of the Arthurian cycle and other textual traditions. Their representations of historic events were heavily novelized, fleshed out with lots of concrete details representing the procedures and protocols of daily life at court. While the epic traditions of Western Europe such as The Chanson de Roland, Cantar de Mio Cid, and Beowulf celebrated excellence in arms, in the Romance authors subordinated martial prowess to abstract ideals such as love or faith. This formula, of the hero and heroine separated and the adventures that eventually bring them together, was a winning formula that, far from being a uniquely French or English innovation, emerged as a Mediterranean literary practice during the twelfth century, one with roots in Byzantine and Roman antiquity.

However, the romance in France and Iberia is only one piece of the picture. Though literary historians (especially of Western European languages) promote a narrative by which the Arthurian legends were first developed into prose romances by French writers in the twelfth centuries and imitated by other traditions in subsequent centuries, romance was really more of a Mediterranean phenomenon. Authors working in Greek, Arabic, and various Romance languages all contributed to the development of what we might call the medieval Mediterranean romance during this period (Agapitos and Mortensen; Kinoshita). Thus the tradition of chivalric romances of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries that became so popular in the early age of print in Iberia and beyond, such as Tirant lo Blanch and Amadís de Gaula, among others, were exemples of a pan-mediterranean culture of romance. In this textual tradition, the lands of the Mediterranean were the stage for the romantic and military exploits of heroes who fought in the name of their beloveds, their kings, and their god. These heroes championed the causes of Islam, Byzantium, and Latin Christendom variously. In the final analysis they championed our need to take a messy, confusing, dangerous world, and have it all make sense, with cut and dried moral values and clear winners and losers.

Such romances were very popular in Aragon and Castile during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Arthurian romances were translated into Iberian languages since the fourteenth century. The following century saw the appearance of original romances penned by authors from the Iberian Peninsula such as Tirant lo Blanc, Curiel e Güelfa, and Amadís de Gaula. The heroes of these books had wide-ranging adventures throughout the Mediterranean, and often ended up as Emperor of Constantinople, both in imitation of the events surrounding the Fourth Crusade and as a bit of wish-fulfilment following the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453.

We should remember, however, that Hispano-Arabic authors wrote romances as well. We have Ziyad ibn Amir al-Qinani, written in the twelfth century, and Qissat Bayad wa-Riyad from the end of the thirteenth. Arabic Romances written in the East, such as the Sirat Anatar and Sirat al-Zahir Baybars, found audiences in Granada, Seville, and Valencia. These Arabic and Romance-language chivalric romances intertwined both historically and literarily. Both traditions of chivalric romance share common settings, historical bases, and to a certain extent, aesthetic conventions, especially in their descriptions of courtly life.

These romances were often the stage for geopolitical drama. Authors projected the political and spiritual concerns of the day onto the pages of boy meets girl, boy loses girl stories. These heroes and heroines played out their dramas against the backdrop of the crusades, the territorial struggles between Islam and Christianity, the grand proselytic dreams of the preaching orders and the kings who supported them, the struggles between Rome and the kingdoms of Latin Christendom, between Byzantium and the West. Romances novelized these concerns, embodying them in the figures of eponymous heroes and heroines who battled, were shipwrecked, and joyfully reunited on the thrones of great empires real or imagined

In Spain this Mediterranean drama played out at home. Crusade was not something that took place “in a galaxy far, far away.” Since before the first crusade, Christian Iberian monarchs had received Papal Bulls of Holy War encouraging their efforts to eliminate Islamic political power on the Peninsula. Just as French and Catalan romances reflected the Crusades, Iberian romances reflected the Aragonese expansion into the Eastern Mediterranean, and the problem of al-Andalus. Thus the thirteenth-century Castilian Flores and Blancaflor imagines the conversion of the Muslim kingdom of Almería, and the Catalan Tirant lo Blanch imagines a successful Fifth Crusade in which the hero becomes Emperor of Constantinople.

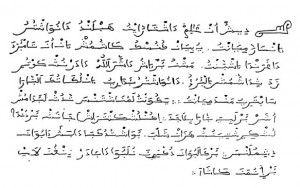

But what does a crusading novel mean for a Muslim readership in Christian Spain? The conquest of Granada in 1492 by the Catholic Monarchs Isabel and Ferdinand may have put an end to Islamic political power on the Peninsula, but it was far from the the last cry of Islamic culture and religion. Although all Spanish Muslims were forcibly baptized at the beginning of the fifteenth century, Islam continued to flourish, unofficially and in varying degrees of secrecy, until the early seventeenth century, when the so-called Moriscos, the descendents of those converted Muslims, were expelled from Spain. During the sixteenth century, Moriscos produced their own clandestine literature that circulated in manuscript alongside the emergent print culture of the mainstream. This aljamiado literature was Castilian (or Aragonese) written in Arabic letters. The term aljamiado is derived from the Arabic `ajamiyya, meaning non-Arabic language (Galmés de Fuentes, “Lengua y estilo”).

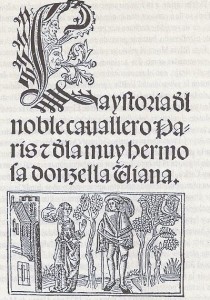

Most aljamiado texts were religious, but a few are modeled after the popular poetry and fiction of the times. Historia de los amores de Paris y Viana was a popular adaptation of the fourteenth-century French chivalric romance Paris et Vienne. It is a typical romance that takes place on a mediterranean stage and is thought by some to be a historical allegory for the French crown’s annexation of the Dauphiny of Albon (Auvergne) (Baranda). The adventures take the protagonists from France to Constantinople to Damascus to Cairo.

The aljamiado manuscript (ca. 1550) of the popular chivalric romance Historia de los amores de París y Viana (The Story of the Romance of Paris and Viana) demonstrates that Morisco readers were aficionados of popular mainstream fiction (Galmés de Fuentes, París y Viana). However, cultural, religious, and political condition makes them a problematic audience for a text with hegemonic Christian values. The mere existence of the aljamiado Paris y Viana poses a series of difficult interpretative questions: How does an audience who is persecuted for their Islamic religion read the exploits of Christian heroes who risk everything to aid the Crusaders in their struggle against Islam? How do readers who are prohibited by law to read or speak Arabic read a Christian hero who learns Arabic so he can travel undetected through the Arab world? The work’s hero, Paris, is a crusader who in one episode goes undercover in the Muslim East to rescue the Dauphin and gather intelligence for the French crusaders. What did Morisco readers make of a Christian hero who goes undercover in the Muslim East, growing out his beard and learning to ‘speak Morisco’ on a recon mission for the Fourth Crusade?

On the one hand, Paris y Viana was a very popular novel, and people like popular novels, even when the ideologies and perspectives within them do not directly reflect the interests of the reader (Hadjivassiliou). People are complicated, and our practices do not always flow directly from our professed ideologies or beliefs. On the other hand, there is no denying the irony of Morisco readers of Paris y Viana risking imprisonment or worse (by possessing an Arabic manuscript) in order to read the exploits of a hero whose goal is ostensibly to eradicate Islam from the Levant, and who disguises himself in traditional dress that directly evokes the Morisco dress outlawed in Granada in the mid-sixteenth century, as the Memorial of Francisco Núñez Muley reminds us (Núñez Muley). Yet it may have been precisely the act of disguising one’s self, of passing as Morisco, that attracted Moriscos to Paris y Viana. They were required in many cases to pass as Christians, to learn Castilian and forget Arabic, to assume a new identity in order to pass undetected by the authorities (Jaramillo). They were forced, like the Jews who had converted to Catholicism to remain in Spain after the 1492 edict of expulsion, to pass in order to survive. The difference was that the Moriscos, unlike Paris, who donned his ‘Moorish’ disguise as part of a great pan-Mediterranean adventure, had to do so in their own country, in their own towns, among their own families.

Thinkers such as W.E.B. Du Bois, Frantz Fanon, and Homi Bhabha grapple with how subaltern discourse imitates and reacts to the cultures and values of the majorities among which they live. Du Bois famously coined the term ‘double consciousness’ in his book The Souls of Black Folk. Writing of African Americans, he described (with some slight alteration indicated in brackets) a “sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness,— [ a Spaniard], a [Morisco]; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder” (Du Bois 3). Such theories, carefully retrofitted to respect the historical difference between twentieth-century US and sixteenth century Spain, may help to shed light on this example of minoritarian literary culture.

Works Cited

- Agapitos, Panagiotis A, and Lars Boje Mortensen. Medieval Narratives between History and Fiction: From the Centre to the Periphery of Europe, C. 1100-1400. Copenhagen; Lancaster: Museum Tusculanum Press ; Gazelle [distributor], 2012. Print.

- Baranda, Nieves. “Los problemas de la historia medieval de Flores y Blancaflor.” Dicenda 10 (1992): 21–39. Print.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. The Souls of Black Folk. New York: Bantam Books, 1989. Print.

- Galmés de Fuentes, Alvaro, ed. Historia de los amores de París y Viana. Madrid: Gredos, 1970. Print.

- —. “Lengua y estilo en la literatura aljamiado-morisca.” Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica 30 (1981): 420–440. Print.

- Hadjivassiliou, Sheela K. U Oregon Span 507 Spain and Islam (Winter 2014). Class discussion. 12 Mar 2014.

- Jaramillo, Jon. U Oregon Span 507 Spain and Islam (Winter 2014). Class discussion. 12 Mar 2014.

- Kinoshita, Sharon. “Medieval Mediterranean Literature.” PMLA: Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 124.2 (2009): n. pag. Print.

- Núñez Muley, Francisco. A Memorandum for the President of the Royal Audiencia and Chancery Court of the City and Kingdom of Granada. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

A preliminary version of this post was written as a position paper for the “Assimilation and Exchange” Roudtable at the Winter 2014 Symposium of the UC Mediterranean Seminar Multi-Campus Research Project, San Francisco State University, 7 March 2014. Thanks to the organizers, Profs. Fred Astren (SFSU), Sharon Kinoshita (UCSC) and Brian Catlos (Colorado and UCSC). Thanks also to my graduate students in Spanish 507: Spain and Islam (Winter 2014) some of whose insights I include here.