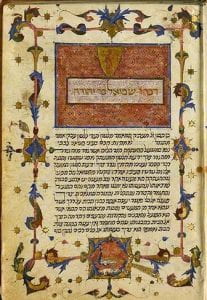

Copenhagen Maimonides f7, Introduction of translator Samuel ibn Tibbon

As a diasporic civilization, Judaism is a moveable world in itself. Heinrich Heine famously quipped that the Torah is a portable homeland, and so Jewish culture provides us with an excellent example of how texts, artifacts, and ideas travel and are transformed in different contexts.

The case of the Copenhagen Maimonides is exemplary of this condition. While the grand narrative of the movement of Aristotelian thought in Europe focuses on the Parisian Averroist controversy of the thirteenth century, the dissemination of Aristotelian thought in the Jewish communities of Spain and France provides a fascinating complement with which to nuance or enrich the story of Averroism in the Latin West.

Just as the Andalusi thinker Muhammad ibn Rushd worked to reconcile the natural philosophy of Aristotle with Islamic revelation, so too did his near-contemporary, the Andalusi Jew Musa ibn Maimun, known to European Jewry as Moshe ben Maimon and to the Latin West as Maimonides, for the Jewish world. His groundbreaking writings on the relationship between Greek philosophy and Torah ignited a centuries-long controversy in Europe’s Jewish communities that in some ways has never ended.

The Copenhagen Maimonides is textual and material witness to this culture war between Maimonideans and traditionalist Jewish scholars who vied for influence and power during the Middle Ages. The fourteenth-century Catalan manuscript of Maimonides’ Guide for the Perplexed is illuminated by the atélier of Ferrer Bassa, a fourteenth-century Catalan Christian artist, no doubt well familiar to our colleagues in Art History, whose cv includes works such as Maria of Navarre’s Book of Hours, and the Anglo Catalan Psalter. This material and aesthetic enmeshment of Jewish and Christian material culture is emblematic of the threat Maimonidean Aristotelian thought posed to more traditional approaches to Jewish revelation that sought to isolate, or protect (depending on your position) Jewish thought from the intellectual and social culture of the dominant Christian majority.

This manuscript is an emblem of the cultural moment of the Jewish elites in southern France and Spain in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, in that it brings together the questions of internal divisions within Jewish communities as well as their relationship with the dominant Christian majority and the extent to which Jews shared cultural values with their Christian neighbors.

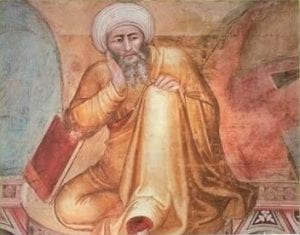

Ibn Rushd aka Averroes

Fresco of Averroes by Andrea de Bonaiuto (14th c.) (source: wikipedia.org)

Muhammad ibn Rushd lived in al-Andalus in the twelfth century, during the Almohad period. He was a judge for the Almohad Caliph and was responsible for a number of commentaries on the works of Aristotle, that had been circulating in Arabic for some two hundred years by his time. His major achievement was to reconcile Aristotle’s natural philosophy with Islamic doctrine. He argued that philosophy was not only permissible within the framework of Islam, but necessary to knowing God’s creation and God’s will. He drew criticism both from neoplatonists and from those opposed to the study of natural philosophy, but perhaps due to the variety of acceptable approaches to Islamic law, did not suffer persecution for his more unpopular ideas.

Ibn Rushd’s natural philosophy was very influential in the Latin West, where translated a number of his works into Latin in during the thirteenth century. Scholars of these works attracted criticism. While Rome did not consider Aristotle’s works in principle to be heretical, some of the conclusions Ibn Rushd drew, particularly those regarding the nature of the relationship between the individual and God, were condemned.

Musa ibn Maimun aka Rambam aka Maimonides

Statue of Maimonides in his hometown, Cordova (source: wikipedia.org)

The most influential interpreter of Aristotelian natural philosophy in Jewish world was Musa ibn Maimun, known in Hebrew as Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, by his Hebrew acronym RAMBAM, or as Maimonides in Latin. Maimonides was born in Cordova during the so-called Tafia period that followed the disintegration of the Andalusi Umayyad Caliphate but later fled persecution at the hands of the Almohads to North Africa where he lived for some time. Eventually he made his way to Fustat where he served as nagid or leader of the Jewish community as well as court physician to the Ayyubid Sultan, Saladin. He wrote revolutionary works in a number of fields, but is best known for his works of biblical and talmudic commentary characterized by his signature rationalist approach to interpreting Torah. His most influential works are the Kitab al-Siraj, Sefer ha-Mishnayot in Hebrew, a commentary on the Mishna; the Mishne Torah, a comprehensive codification of Jewish law, and the Dalálat al-Ha’irin, Moreh Nebukhim, or Guide for the Perplexed, his synthesis of Aristotelian natural philosophy and Jewish doctrine. It is the Royal Library’s fourteenth-century copy of the Guide that concerns us today, but a bit about Maimonides’ other influential works will help to set the stage for the scope of his influence in Jewish civilization in general.

The Maimonidean Controversy

The work of Maimonides had been very influential in Jewish thought on the Iberian Peninsula since his lifetime. His works were at the center of the curriculum for Jewish elites in Castile and Aragon. French Jews who were at a further distance from Maimonidean thought and who had not adopted a rationalist approach to the study of Jewish revelation found his works and interpretations of his works more problematic. At the core of the debate is a struggle between philosophy and theosophy. Rationalists under the banner of Maimonides argued that philosophy, and the exercise of God-given human reason was the best way to know God, by observing his creation and arriving at logical conclusions regarding the nature of the divine and of the relationship between the human and the divine. Traditionalists rejected philosophical approaches to revelation as heretical in favor of a theosophical approach by which all knowledge is a product of divine revelation, and that everything that is permissible can be learned by study of the Torah and its commentaries. This debate will seem familiar to many; it is the great-great-grandparent of current debates regarding creation, and the role of revelation in the organization of society.

Banned in Montpellier

source: wikipedia.org

It’s important to remember that the backlash against some of the interpreters of Maimonides was directed not against the work or person of Maimonides himself, but rather against later interpretations of the Guide that were understood to threaten traditional doctrine in Maimonides’ name. Even the most ardent opponents of Maimonideanism did not object to Maimonides as an authority, or even to many of his propositions that were certainly provocative to more conservative interpreters of Jewish tradition. Eventually these concerns gave rise to two groups of Rabbis spread across Provence, Aragon, and Castile, who advocated for or against these later interpretations of Maimonides’ natural philosophy.

In the first quarter of the thirteenth century, Rabbi Solomon ben Avraham of Montpellier and his students were concerned that interpreters of Maimonides were abrogating Jewish law for their own purposes, all the while hiding behind Maimonides’ authority (Silver 150–51). In 1232 he promulgated a ban on Maimonides’ Guide. In so doing he ignited a controversy. Another group of Maimonists formed not far away in Lunel, enlisting influential rabbis in Castile and Aragon for support. In the same year, they issued a ban on anyone interfering with the teaching of philosophy. Jewish communities in Aragon signed on to it, and a line was drawn in the sand (Silver 151). Each side enlisted the greatest minds of their generations to support their cause. The Catalan Rabbi Nahmanides, who would later debate the Dominican Friar Paul before King Jaume I himself, tried to reconicle the two sides, but was not successful (Silver 165).

In Aragon in particular, the Controversy mapped onto tension between religious and secular leadership (Silver 166), with the Mamonists coming down on the side of secular leadership and the anti-maimonists on the side of the rabbinate. As the controversy developed, the nexus between religious and temporal issues remained at its center.

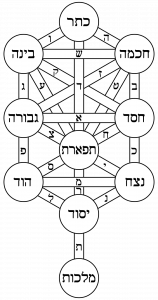

Diagram of kabbalistic sefirot (divine emanations) (source: wikipedia.org)

The Maimoideans eventually prevailed, while the traditionalists dedicated themselves to the study of Kabablah or Jewish mystical theosophy, developing important centers of its study in Provence, Aragon, and Castile. Traditionalists continued to agitate against philosophy, especially in Provence., where Rabbi Solomon Ibn Adret wrote a ban against Provençal Maimonists in 1305 on the grounds that their allegorical interpretation of the Bible violated Jewish tradition (Forcano 94).

The Copenhagen Maimonides in its cultural context

Fourteenth-century Castile and Aragon saw a good deal of cultural commonality between Jewish and Christian élites. Jews spoke the same languages as their Christian neighbors, and Jewish élites, dependent as they were on good graces of their king, were avid consumers and producers of many of the cultural practices of the court. Typically, the closer individual Jews were to court, the more assimilated they were to the culture of the dominant majority in matters other than religion.

An iconic cosmopolitanism

source: wikipedia.org

However, despite the very real philosophical and doctrinal debates that surrounded interpretations of the Guide, the book itself became iconic of Jewish cosmopolitanism and a willingness to engage with the non-Jewish world. Just as their detractors painted Maimonists as free-thinkers and assimilationists who favored secular leadership over the rabbinate, so too did cosmopolitan Jewish elites look to the Guide not only as an important source of information, but also as a symbol of their role as mediators between temporal power and the Jewish communities. For them, it was natural that the Rabbi who brought together Greek science and Torah should be an icon of their own cultural position between the Christian court and the Jewish community. It is in this light that we must understand the Copenhagen Guide. It signaled cosmopolitanism and sophistication. As a tangible artifact illuminated by a Christian artisan, it was an emblem of the Jewish notable’s role in the political economy of the times.

The Cophenhagen Maimoinides

The manuscript is richly illuminated and bound with the introduction of the translator Samuel ibn Tibbon, as well as the translator’s glossary of Aristotelian terms in Hebrew. It contains a number of marginal illuminations as well as some larger historiated illuminations, all of which are clearly identifiable as the work of the atelier of Ferrer Bassa, a Christian Catalan artist who also illuminated the Anglo-Catalan Psalter, the Book of Hours of Maria of Navarre, and the Catalan Micrography Mahzor (NLI MS Heb 8º6527), a prayer book for the Jewish high holidays. In Castile and Aragon at this time, Jewish artisans sometimes worked on Christian art and in some cases, Christian artisans produced works of Jewish art. The Copenhagen Guide is one of these examples.

A new Maimonides?

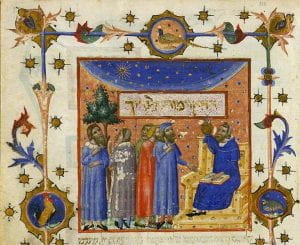

Copenhagen Maimonides, Danish Royal Library Cod Heb 37, f227v

The manuscript’s patron was Menahem Betzalel, a Jewish physician in the service of Peter IV of ‘the Ceremonious’ of Aragon. The king also patronized works by the atélier of Ferrer Bassa, and so Betzalel’s commission of the Guide reinforced his relationship to the king and the culture of the court. As a royal physician himself, Betzalel may have imagined himself a new Maimonides, and his possession of the deluxe manuscript of the Guide may have signaled this identity to members of the Jewish community of Barcelona.

Evangelist Remix

Reuse of traditional symbols of Evangelists to illustrate discussion of Ezekiel’s vision (Cod Heb 37 f. 403v)

However, it in the redeployment of Christian iconography that this manuscript is remarkable and perhaps unique among Hebrew illuminated manuscripts of the time. In the Guide, Maimonides discusses the vision of Ezekiel described in chapter 1, verses 4-28. In the Christian reading of the Hebrew Bible, the animals that form this fantastic beast are imagined as representing the four evangelists Matthew is an angel, Mark a winged lion, Luke a winged bull, and John an eagle. This allegory of the evangelists was a common image in medieval Christian iconography. In the Maimonides Guide, the illuminator uses a historiated miniature of the Christian icons to illustrate Maimonides’ discussion of the vision of Ezekiel. Chapman points out that Bassa had previously used this illumination in both the Anglo-Catalan Psalter and the Hours of Maria of Navarre, but replaced the banners featuring the names of the Christian saints traditionally associated with the animals (drawn from the Revelations) with the Hebrew word Hakdamah, or “introduction.” Its use in a Jewish manuscript demonstrates for Chapman the manuscript’s cultural ambivalence, but for me it is suggests a kind of openness or self-confidence in adapting materials across confessional groups provided they are not in direct conflict with religious doctrine. While it would be problematic for a Jewish manuscript to attribute sainthood to followers of Jesus, there’s nothing wrong with drawing a fanciful version of the vision of Ezekiel to make the ideas of the Torah more real for Jewish readers; this is simply exegesis, and midrash is full of these kinds of gestures.

In closing, the Copenhagen Maimonides tells two interrelated stories. The first is that of the Movable World, in this case, the journey of Aristotelian natural philosophy from Athens to Baghdad to Cordova to Barcelona. The second is that of the medieval Iberian Jewish communities who adapted and transformed Aristotle’s ideas through the lens of their own experience. For them, the controversy stirred by Ibn Rushd’s and Maimonides’ interpretations of Aristotelian natural philosophy were embedded in broader issues facing the communities: the brittle relationship with the Church and the preaching orders, the social implications of conflicting schools of exegesis, the balance of power between secular and rabbinic leadership within the Jewish community, and, for the elites, the challenge of living as a powerful member of a religious minority negotiating between the royal court and the kahal, or Jewish community.

Bibliography

- Brown, Stephen. “The Intellectual Context of Later Medieval Philosophy: Universities, Aristotle, Arts, Theology.” Routledge History of Philosophy Volume III: Medieval Philosophy, edited by John Marenbon, Routledge, 2003, pp. 188–203.

- Chapman, Katherine Woodson. Image and Identity : Re-Reading the Illustrations of the Copenhagen Maimonides. S.M.U, 2009.

- Forcano, Manuel. “La lletra apologètica de Jedàia ha-Peniní de Bésiers.” Anuari de filologia. Secció E. Estudis hebreus i arameus, vol. 6, 1996, pp. 93–104.

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin. Jewish Book Art Between Islam and Christianity: The Decoration of Hebrew Bibles in Medieval Spain. Brill, 2005.

- Leaman, Oliver. Averroës and His Philosophy. Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Sánchez, Tomás Jesús Urrutia. “Saber de sabios y saber de profetas: la controversia maimonideana y Sem Tob Ibn Falaquera.” Revista española de filosofía medieval, no. 16, 2009, pp. 57–68.

- Silver, Daniel Jeremy. Maimonidean Criticism and the Maimonidean Controversy, 1180-1240. EJBrill, 1965.

This post is a version of a conference paper I gave at the 2019 meeting of the Centre for Medieval Literature, “Shared Worlds,” held in Copenhagen at the David Collection and the Danish Royal Library. My thanks to the Centre for their invitation to participate.