Translate this. [photo: Bible Leaf. Vulgate Bible. France. Circa 1150. source: Graduate Theologial Union]

The translation of Biblical texts into the European vernaculars was one important laboratory for medieval fiction. Alfonso’s translations of biblical narratives drew on Jewish biblical commentaries that sought to bring Biblical language (and the reality it represented) in line with local, contemporary life of Jewish communities. As such, it was a model for literary fiction in that it strove to take material, ideas, and worlds described in classical language, and make them relevant to contemporary culture and daily life.

Bible as history paves the way for fiction

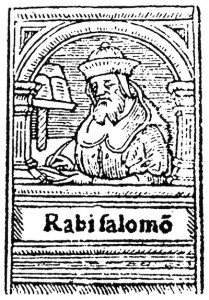

Readers of medieval history did not expect histories to be empirically correct representations of historical events. Rather, they looked to them to provide stories of great deeds of the past told in an entertaining and convincing fashion. In this way, their function was closer to that of the modern historical novel than the modern history book. For us, medieval history writing is a Renoir: moving, inspiring, beautiful, but hardly photographic; we might say the same of Biblical narrative, which only the most fundamentalist regard as accurate in the same way they would expect from a history book. For this reason, it was far less problematic in the thirteenth century to include biblical texts in works of historiography than it would be today. In order to make this biblical history come alive in the vernacular, Alfonso’s translators brought to bear the tools and methods of Jewish exegesis, in ways that would have implications for the development of vernacular prose fiction.It seems counterintuitive that a Christian king should resort to Jewish biblical commentaries in order to render the Bible into Spanish. It was not as if there were a shortage of Christian scholars who were capable of translating the Latin Vulgate into Spanish. Why bring Rabbis into the picture? Alfonso had long demonstrated a keen interest in scriptural and exegetical traditions of his subject religious minorities. His nephew Don Juan Manuel, himself an important voice in early Castilian literature, relates the following:

He ordered translations of the Muslim scriptures…. also he ordered translations of the Jewish scriptures and even their Talmud and another discipline that the Jews keep hidden that they call Kabbalah. He also translated into Castilian all laws Ecclesiastical and Secular. What more can I tell you? No man can say how much good this noble king has done to grow and illuminate knowledge (Juan Manuel 2: 510–520; Alvar 49).

Alfonso ordered translations of the major sacred texts of Islam and Judaism. He did so not in order to convert his subject Jews and Muslims, but to satisfy his curiosity about the world and its history. His court was a major center of translation of Arabic science into Castilian, and he employed Christian, Muslim, and Jewish scholars in these projects. After his death he enjoyed far greater renown for his patronage of science and arts than he ever did as a statesman.

By Alfonso’s time, Castile had long been an important center for Biblical translation, and Jewish translators often worked alongside their Christian counterparts to produce these translations. There are numerous episodes, motifs, and methodological earmarks of the work of Jewish exegetes in the biblical material in the General estoria (Peña Fernández). Alfonso’s translators explain aspects of the material world of the bible in contemporary terms, a tactic prevalent in the work of important medieval Jewish exegetes such as Rashi of Troyes and Abraham ibn Ezra of Navarre, both of whom brought examples from the contemporary cultural life of the community in order to give new relevance and meaning to the biblical storyworld. In my previous post on the General Estoria, I mentioned a few examples from the Song of Songs that you can read here.

The contribution of Jewish biblical commentary to the development of fictional worlds

It’s in there [Guillaume de Paris, Postillae maiores totius anni cum glossis et quaestionibus (Lyon, 1539) . souce: wikipedia]

Jewish exegesis is also in large part concerned with making scripture and earlier commentaries more relevant to the lives and realities of contemporary Jewish communities. To this end they often employ the vernacular to explain an object, animal, or other realia whose meaning is unclear in the Hebrew or Aramaic. The twelfth century exegete Rashi of Troyes in particular, is well-known for his use of medieval French to explain difficult etymons and concepts, and it is perhaps no accident that he was working at the dawn of vernacular literary composition in France, when Troubadours began to sing and authors of Romances began to write in French and not Latin.

Like translations, exegetical texts are doing the work of bringing the text over, closer to the lived realities of the audience. Just as a translator is concerned with rendering a source text into a target language, an exegete is concerned with rendering the world of the text into the target vernacular culture, the bridge between classical traditions.

Translation is a form of interpretation, and just as biblical commentary expands the meaning of scripture and aligns the text with the reality of new generations of readers, the translation of scripture into the vernacular itself a form of biblical commentary, one that reflects the values and practices of the current generation.

![True, but not Real [Lancelot and Guinevere, north-eastern France or Flanders (St Omer or Tournai), 1316, Additional 10293, f. 199. source: British Library, Medieval Manuscripts blog]](https://davidwacks.uoregon.edu/files/2016/07/prose-lancelot-28mujtc-233x300.jpg)

True, but not Real

[Lancelot and Guinevere, north-eastern France or Flanders (St Omer or Tournai), 1316, Additional 10293, f. 199. source: British Library, Medieval Manuscripts blog]

Vernacular fictional worlds

Writing in the vernacular catalyzes the make-believe function of fiction, because the familiar sounds of everyday speech (even if not one’s native language) make the alternate reality of the fictional world more plausible, more believable, and more easily provoke the suspension of disbelief key to the audience’s participation in the covenant of fiction. This vernacularization enhances the ‘as-if’ nature of fiction, establishing more vivid points of reference between the fictional and ‘real’ words. Medieval Jewish exegetes knew this, and took pains to map the Biblical and ancient rabbinical worlds onto contemporary vernacular culture, making frequent use of the vernacular languages they spoke in order to do so. This was also the case in the arts: medieval biblical illuminations of stories set in the ancient fertile crescent feature characters dressed in contemporary costume. Alfonso’s translators took a page from their book in striving to make biblical texts relevant to the concerns and sensibilities of Alfonso’s court, a court that strove to elevate the vernacular of its subjects to the level of a classical tradition. In so doing, I believe they sowed seeds of what would later become modern fictionality’s attention to realistic detail and empirical plausibility in creating new worlds for new readers.

![David, who's your tailor? [Photo: David loads provisions in the Maciejowski Bible, New York, Morgan Library Ms M. 638, f. 27 Source: wikimedia commons]](https://davidwacks.uoregon.edu/files/2016/07/david-29k8dnw-300x190.jpg)

David, who’s your tailor?

[Photo: David loads provisions in the Maciejowski Bible, New York, Morgan Library Ms M. 638, f. 27 Source: wikimedia commons]

Alvar, Manuel. “Didactismo e integración en la General estoriaI (estudio del Génesis).” La lengua y la literatura en tiempos de Alfonso X. Actas del Congreso internacional (Murcia, 5-10 de marzo de 1984. Murcia: Universidad de Murcia, 1985. 25–78. Print.

Juan Manuel. Obras Completas. Madrid: Gredos, 1982. Print.

Peña Fernández, Francisco. “La Relatividad de Las Cosas: Heterodoxy and Midrashim in the First Chapters of Alfonso X’s General Estoria.” eHumanista (2013): 551. Print.

This post is a version of a paper I gave at the conference “Theorizing Medieval European Literature”, Centre for Medieval Literature, (University of York/University of Southern Denmark) at York, July 2, 2016. Thanks very much for the Centre’s directors, Profs. Elizabeth Tyler, Lars Boje Mortensen, and Christian Høgel, for the invitation.

It is part of a collaborative, online digital critical edition of the Biblical material in Alfonso X’s General e grant estoria titled “Confluence of Religious Cultures in Medieval Iberian Historiography: A Digital Humanities Project” and supported by funding from Social Science and Humanities Research Council, Government of Canada

![Hardly photographic [Renoir, Chestnut Trees in Bloom (1881) Source: wikimedia commons]](https://davidwacks.uoregon.edu/files/2016/07/renoir-2hgul6l-300x235.jpg)