In the last post about the Aljamiado manuscript of Paris and Viana (Aragon, ca. 1560) we saw an example of a cross-cultural romance of two Christians read by a Muslim audience, in which the protagonist ‘passes’ for Arab in his travels in the Eastern Mediterranean. In this case, it is the protagonists themselves who cross cultures. Flores is the son of the Muslim king of Almería (al-Andalus) and Blancaflor is the daughter of a captive French Christian Countess. The two are raised together in the court of Almería:

In the last post about the Aljamiado manuscript of Paris and Viana (Aragon, ca. 1560) we saw an example of a cross-cultural romance of two Christians read by a Muslim audience, in which the protagonist ‘passes’ for Arab in his travels in the Eastern Mediterranean. In this case, it is the protagonists themselves who cross cultures. Flores is the son of the Muslim king of Almería (al-Andalus) and Blancaflor is the daughter of a captive French Christian Countess. The two are raised together in the court of Almería:

en vno los criaran, e mamauan vna leche, e en vno comien e beuien, e en vn lecho se echavan. E porque fazien vna vida queriense bien ademas (57) (‘they were raised together, and nursed the same milk, and ate and drank together, and slept in the same bed. And because they led one life they also loved one another very much’).

Naturally they fall in love, which is a problem because Flores is Muslim and Blancaflor is Christian. In order to separate them, King Fines sends his son Flores to Seville, sells Blancaflor into slavery, and fakes her death. He cannot countenance a Christian daughter-in-law, and contrives to make Flores

amar a otra que le pertenezca para casamiento e que sea pagana de nuestra ley. Ca desaguisada cosa me semeja que nuestro fijo sea casado con fija de cristiano. (58) (‘love another women who is fitting for him to marry, and who be a pagan of our law. For is seems to me untoward that our son be married to the daughter of a Christian.’)

Eventually he tells Flores the truth, and Flores then embarks on a pan-Mediterranean adventure to save his beloved. There is a happy ending in which the lovers are reunited, Flores converts to Christianity, and brings the kingdom of Almería into Christendom: Vivieron felices y comieron perdices (‘They lived happily and ate quail’).

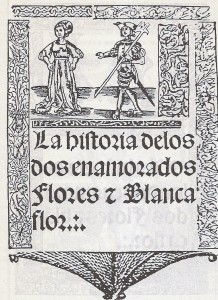

This is the version of the French Floire et Blancheflor (Crónica de Flores y Blancaflor, ca. 1300 to its modern editors) we find woven into the Castilian chronicle known as Estoria de España. The Estoria was the section of the massive historical project begun by Alfonso X of Castile-León (r. 1252-1284), the Primera crónica general, meant to record all of human history from creation to the current regime. In the twelfth-century French version, the story of Floire and Blancheflor was about emphasizing the Carolingian legacy of the current regime in a time when France was once again entangled with Islam in the Crusades (Baranda).The French Floire and Blancheflor validated the crusades as the continuation of Charlemagne’s struggle with Islam in Spain. However, when in the following century the romance is adapted by a Castilian historiographer for purposes of validating domestic crusade, the adventures of the star-crossed young lovers finding each other against all odds becomes the story of Castilian political power and Christian proselytizing in al-Andalus.

King Fruela I of Asturias – Flores asks him to intercede on his behalf in Rome to estblish a Bishopric at Córdoba, and later teams up with him to reduce Toledo and Zaragoza to tributary states.

Source: Wikipedia

The romance of Flores and Blancaflor is tightly interwoven, in alternating chapters, with the history of the kings of Asturias in Northern Spain during the 8th-10th centuries and their struggles with the Muslim kings of al-Andalus to their south. The story of this Asturian ‘resistance’ to the Muslim domination of the Iberian Peninsula was already in the thirteenth century used to justify further conquests in al-Andalus and North Africa, part of an ideology and trajectory of conquest that would come to bring all of al-Andalus and eventually a great part of the known world under the flags of Castile-León and Aragon. Thus this love story between Christian and Muslim is textually fused with the foundational narrative of Christian Spain.

As in the case of the Spanish adaptation of the French romance Paris et Vienne, conquest, conversion, and crusade mean something different in Castile than they do in France. For French audiences, tales of Saracen queens who convert to Christianity were free to fantasize what for France by the eleventh century was the stuff of distant legend in the context of a far-away imperialist project (Kinoshita). For Spain, however, conversion and domestic crusade was the story of daily life. The metaphors of mixed marriage and conversion for the drama of Andalusi and Castilian history were part of both local history, and to a significant extent, daily reality. Just as French royals often intermarried with the royal houses of neighboring kingdoms, Christian Iberian royals had long intermarried with the sons and daughters of Andalusi rulers. In the thirteenth century, daily coexistence with Muslims in Christian kingdoms as well as political conflict with the Kingdom of Granada was not something that took place, as in the French version, “long long ago” and “far far away.”

Charlemagne instructing Louis the Pious. Grandes Chroniques de France, France, Paris (BnF Français 73, fol. 128v)

Source: Wikipedia

When the French fantasy of the Muslim other is retrofitted for Iberian audiences, the result is a curious internal-Orientalist novelized encounter between Christianity and Islam in which the role of the Muslim other is transformed from crusade metaphor to national historical allegory. At the same time, Iberian monarchs are using the French sword against their counterparts across the pyrennes. That is, while the French kings used the romance to legitimize their own dynastic claims, Sancho IV appropriates the narrative for his own political ends against the French themselves, stabbing them, as it were, with their own Charlemagne.

In Iberia, however, the question of Christian and Muslim is complicated and the literary representation of the foster siblings/lovers is an allegory for a local history with real political and social implications. Conversion to Christianity is not only a historical allegory of conquest, but a daily reality as well, one given ample attention by Dominican friars and other religious who devoted their lives to bring Iberian Muslims and Jews into the flock (Hames; Tartakoff).

In Flores y Blancaflor (and, interestingly, not in the older French version), Flores is predisposed to convert to Christianity because he was nursed by a Christian woman, the French countess who is also the mother of Blancaflor. The Muslim Flores is nursed by the countess, who has “good milk.” Ostensibly this predisposes him to Christianity, ca la naturaleza de la leche de la Cristiana lo mouio a ello (“for the nature of the Christian milk moved him to that”) (53)

His eventual decision to convert is then natural, and explained in terms of the science of the day. This idea of a biological/chemical basis for religious identity predates the fifteenth-century concept of limpieza de sangre, by which religious identity (Jewish or Muslim) was understood to adhere in the blood, despite the individual’s actual religious beliefs (Edwards; Kaplan). In the fifteenth century this was a way to deny power and privilege to new converts from Judaism and Islam. In the late fourteenth, the biological determination of Flores’ authentic religious identity is a metaphor for the conquest of al-Andalus and the ideology of domestic crusade.

The idea that a renegade Muslim born of mixed Christian and Muslim parents finds frequent expression in medieval Spanish literature. In the legend of the Siete Infantes de Lara, the Muslim-turned-Christian hero Mudarra is son of Gonzalo Gustios and a Muslim courtier woman, in some (very anachronistic) versions the sister of the Hajib Almanzor (de facto Caliph of al-Andalus) himself. The narrator attributes both his outstanding moral character and physical beauty to his Christian heritage, which eventually ‘wins’ out over his Muslim heritage and makes him a Christian hero. Likewise, the Muslim Abenámar (i.e., Ibn `Ammar) protagonist of the eponymous ballad, was born of a Christian mother who told him never to lie. Like the Andalusi Flores, who took in moral excellence along with the ‘Christian milk’ of the French countess, these protagonists embody the dream of conquest and conversion that was the dominant ideology of the times. Their strength of character and authority stem not from their language or culture, but from their Christian biological heritage.

In the case of the Crónica de Flores y Blancaflor, this Christian heritage becomes a metaphor for the ideology of Christian conquest and crusade, perhaps of ‘reconquista’ avant la lettre. The tale of the two lovers serves a dual purpose: on the one hand, their union brings together the political legacies of Charlemagne and the Umayyad Caliphate in the court of Sancho IV, under whose reign the text was completed. On top of this bit of historigraphical legitimation, very much in keeping with the times, we have the historical allegorization of the conversion of al-Andalus in the person of Flores. The result is a narrative of justification that is simultaneously mimetic, allegorical, and entertaining. The strategy of alternating between the exploits of the Asturian kings and the amores of the two lovers is not just an example of subtle literary politics, it is also a good read to boot. But don’t take my word for it; thanks to the recent edition by David Arbesú, you all can judge for yourselves.

This post is a preliminary version of a paper I gave at the 2014 meeting of the Medieval Academy of America and the Medieval Association of the Pacific, at a panel on “Sites of Encounter: Iberia (2)” Thanks to the panel organizer and moderator Michelle Armstrong-Partida (U Texas, El Paso).

Bibliography

- Arbesú-Fernández, David, ed. Crónica de Flores y Blancaflor. Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studie), 2011. Print.

- Arbesú-Fernández, David. “Introduction.” Crónica de Flores y Blancaflor. Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2011. 1–47. Print.

- Baranda, Nieves. “Los problemas de la historia medieval de Flores y Blancaflor.” Dicenda 10 (1992): 21–39. Print.

- Edwards, John. “The Beginnings of a Scientific Theory of Race? Spain, 1450-1600.” From Iberia to Diaspora: Studies in Sephardic History and Culture. Leiden: Brill, 1999. 179–196. Print.

- Hames, Harvey J. The Art of Conversion : Christianity and Kabbalah in the Thirteenth Century. Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2000. The Medieval Mediterranean, v. 26.

- Kaplan, Gregory B. “The Inception of limpieza de sangre (Purity of Blood) and its impact in Medieval and Golden Age Spain.” Marginal Voices: Studies in Converso Literature of Medieval and Golden Age Spain. Ed. Gregory B. Kaplan and Amy Aronson-Friedman. Leiden: Brill, 2012. 19–42. Print.

- Kinoshita, Sharon. Medieval Boundaries: Rethinking Difference in Old French Literature. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006. Print.

- Tartakoff, Paola. Between Christian and Jew: Conversion and Inquisition in the Crown of Aragon, 1250-1391. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012. Print.