[This post includes material later revised and expanded in Double Diaspora in Sephardic Literature: Jewish Cultural Production before and after 1492 (Indiana University Press, 2015)]

The debate over the relative roles of military force and political rhetoric in governance is very, very old. And while the familiar dictum “the pen is mightier than the sword” may now be received wisdom, for hundreds of years it was a site of contention. In Spain during the 12th-14th centuries, authors wrote version after version of the literary debate between the pen and the sword in Arabic and Hebrew.

Students of European literatures are familiar with later debates on the subject of arms and letters. The Arms vs. Letters debate was well-covered territory during the Renaissance and on into Modernity. Baldassare Castiglione includes one in the first part of of The Book of the Courtier (1528), and Miguel de Cervantes has Don Quijote argue vigorously for the superiority of arms over letters in the first part of Don Quixote (ch. 38).

The relative merits of the sword and the pen were frequent subjects of Classical Arab poets during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, but it was not until the 11th century in Spain when the Pen and Sword come forward to speak for themselves as protagonists in a literary debate. Ahmad ibn Burd the Younger wrote the first such debate as part of a panegyric (a poem written in praise of an individual) dedicated to King Mujahid al-Muwaffaq of Denia around the year 1040.

The relative merits of the sword and the pen were frequent subjects of Classical Arab poets during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, but it was not until the 11th century in Spain when the Pen and Sword come forward to speak for themselves as protagonists in a literary debate. Ahmad ibn Burd the Younger wrote the first such debate as part of a panegyric (a poem written in praise of an individual) dedicated to King Mujahid al-Muwaffaq of Denia around the year 1040.

Ibn Burd, a Muslim writing for a king (who as a monarch would probably identify with the sword to some degree, even if he were a bookish kind of king), came to a safe conclusion: the Pen and the Sword are both worthy instruments, and both occupy an honored place at court. In his version, the two instruments trade barbs but eventually work out a downright Utopian love-fest of an ending in which each recognizes the value of the other’s contributions:

What a beautiful mantle we don, and what excellent sandals! How straight the path we walk and how pure the spring from which we drink! A friendship, the train of whose garment we let drag [i.e. ‘in which we luxuriate’] and a fellowship whose fruits we pick and whose wine we taste. We have left the regions of sin a wasteland and its workmanship in ruins, we have wiped out every trace of hatred and returned sleep to the eyelids!

At the end of the 12th or beginning of the 13th century, the Sephardic writer Judah al-Harizi adapted Ibn Burd’s debate in chapter 40 of Tahkemoni, a collection of rhyming prose narratives. Al-Harizi wrote in Hebrew for a Jewish patron who, unlike Ibn Burd’s patron King Mujahid, was not a military leader and whose relationship to sovereign political power was that of a minority courtier, a member of a diasporic culture. Al-Harizi is writing some 50 years before Todros Abulafia penned his troubadouresque verses at the court of Alfonso X. His prose, like that of all Hebrew authors of his time, is shot through with words, images, and set phrases lifted directly from the Hebrew bible.

Jews in 13th-century Toledo did not fight in wars. They provided financial and logistical support for wars, but they were not marching into battle. So, what does a sword mean to a writer who belongs to a community that does not wage war but that is dependent upon the monarch who does?

It should not, therefore, surprise that Al-Harizi’s debate looks a bit different from that of Ibn Burd. He is writing for an audience that typically does not bear arms themselves and who have suffered violence at the hands of the majority time after time. The massacres of Jews in Granada in 1066, in France and Germany in 1096, and the periodic violence against Jews in Christian Iberia were very real reminders that swords were not just something to write about.

Accordingly, the Pen comes up winner in al-Harizi’s version. This is not surprising – in Latin debates between clerks and knights (written by clerks), the winners were always the clerks. But before ceding the field, the sword reminds the pen:

The king reigns through my power: I shout, his enemies cower, leap, and pull down turret and tower. I am my monarch’s shield against all foes: my fear precedes him where’er he goes. His rivals I efface, their camps erase without a trace. All tremble at my blade’s command, before me who can stand?

The Pen counters the he not only provides right guidance for those in power, but is also the instrument of Divine Will and of religion:

My words bind monarch’s heads with light,

my proverbs, the heart with joy.

I cover the earth with the mantle of Law

and no evil stains that cloak;

Through me, God hewed the Tables Two

at Sinai for His folk.

Al-Harizi’s narrator is won over by the pen, who he describes with sword-like attributes:

When I had heard this well-honed story, this sharp-edged allegory, I inscribed his words on my heart with iron pen, that never they might part.

Al-Harizi here reworks Ibn Burd’s debate in a diasporic key. The Jewish community, a class of administrators, financiers, scholars, and merchants, lives by the pen, yet sometimes dies by the sword despite a (usually) privileged relationship to sovereign political power.

Jacob Ben Elazar, writing in Toledo some years after al-Harizi, takes this diasporic interpretation of the debate a step further. His debate is more than a competition for superiority, it is a moral manifesto for a time of intellectual and religious decadence. His pen not only wins the debate, it serves as the moral compass for what Ben Elazar describes as a “generation of fools.”

The debate begins like the others, with each instrument bad-mouthing the other and pointing up their respective weaknesses and faults. The sword calls the pen weak, empty, and inconsequential, while describing himself as the “glory of kings.” The pen tells the sword to “get back into your sheath and calm down,” reminding him that he is abusive and unjust, he spills innocent blood and undermines justice. He holds that he has power that far transcends the temporal powers of the sword. The pen, he explains, can form reality, teach history, morals, and law:

My mouth (i.e. the split opening of my quill where the ink flows) will cause you to know what has happened in the past, the history of princes, kings, and priests who came before us, to the point that you will feel you have been friends with every one of them. Its mouth will speak to your mouth and will inform you about their justice and loyalty, their perversity and their sins. From my mouth you will learn doctrine and wisdom and it will teach you mysteries and deep knowledge.

But then the pen changes the rules of the game. He explains that what is at issue is not whether the pen is better than the sword, but whether humans can live righteously according to God’s law. Both pen and sword are mere instruments, and that neither intelligence nor might are of lasting value. He then launches into a sort of Aristotelian sermon on the unity of God dense will allusions to Sephardic scholarship and worthy of Maimonides, the Spanish-born Rabbi and physician who changed Jewish life forever by continuing the work of Ibn Rushd (Averroes) in reconciling Jewish religion and Greek philosophy:

The principles of all the unities are Eight,

but only of he in whom there is no plurality

you may proclaim that he is truly One, and is the only true God,

who is a refuge since times gone by;

He is not found in any place, only in the thoughts

of the wise man and in the forge of Reason….

Here Ben Elazar is weighing in on a philosophical debate that was causing a serious political rift in the Jewish communities of Castile in the mid-13th century: the Maimonidean Controversy. This debate divided Jewish communities in Spain and Southern France into two camps: those who favored a Judaism that could adapt to the advances in science and philosophy made possible by the translations of Aristotle’s works into Arabic, Hebrew, and Latin (Maimonideans), and those who preferred a more traditional interpretation of Jewish law that shunned any reconciliation with Greek philosphy (Traditionalists).

In broad strokes, this is a debate that should be familiar to those of us living in the US (and other countries) in the 21st century. Many communities are simliarly torn today by debates between believers of Creationism and Evolution, and more generally between various bands of Fundamentalists and Rationalists.

Ben Elazar continues to expound on the unity of God, and his insistence in following this line makes me think that he is circling back to yet another meaning of the Pen versus the Sword, one particularly suited to a diasporic Jewish audience living under Christian rule:

The Almighty truly must be called One

you cannot divide him into pieces, nor can you join him

all of him is that is called One

is indivisible once it is united.

The One that cannot be divided remains

eternally, but the unity that is created, perishes.

Why, in the context of a debate between Pen and Sword, this insistence on God’s essential unity? It doesn’t seem to make sense for either of the interpretations we have so far discussed. The question of God’s unity seems irrelevant to the traditional interpretation by which the Pen represents letters and the Sword arms. Even when the Pen represents Maimonideans (science) and the Sword traditionalists (fundamentalism), it doesn’t add up: neither side is advocating for a plural God.

It is almost as if Ben Elazar here is suggesting a third interpretation: the Pen is the diasporic Jewish community, and the Sword Christian sovereignty, a double-edged sword (pun intended) that presents both a theological threat in the form of the Trinity (the division of God into parts), and a political threat in the form of the ever-present possibility of violence, perhaps violence in the name of same Trinity.

Bibliography

- Alba Cecilia, Amparo. “El Debate del cálamo y la espada, de Jacob ben Eleazar de Toledo.” Sefarad 68.2 (2008): 291-314. [includes debate translated into Spanish]

- —. “Espada vs. cálamo: debates medievales hispánicos.” Homenaje al Prof. J. Cantera. Madrid: Universidad Computense, 1997. 47-56. [study of debates by Ibn Burd, al-Harizi, Ben Elazar, and Shem Tov Ardutiel de Carrión]

- al-Harizi, Judah. The Book of Tahkemoni: Jewish Tales From Medieval Spain. Trans. David Simha Segal. London: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2001. [Chapter 40 containing the debate between the Sword and the Pen is found on pages 303-306]

- Ben Eleazar, Jacob. The Love Stories of Jacob Ben Eleazar (1170-1233?) [Hebrew]. Ed. Yonah David. Tel Aviv: Ramot Publishing, 1992. [Chapter 4 containing the debate between the Pen and the Sword is found on pages 32-40]

- de la Granja, Fernando. “Dos epístolas de Ahmad ibn Burd al-Asgar.” Al-Andalus 25 (1960): 383-418. [includes Spanish translation of Ibn Burd’s Risalat al-sayf wa-l-qalam on pages 399-406]

Photo credits:

- Quill: Clipart Etc. http://etc.usf.edu/clipart/19200/19248/quill_19248.htm. 23 Feb. 2011.

- Sword: Clipart Etc. http://etc.usf.edu/clipart/53200/53289/53289_sword.htm

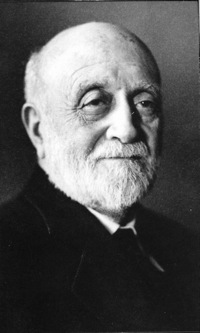

- Maimonides, Moses. Photograph. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Web. 23 Feb. 2011. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/media/75222/Moses-Maimonides-engraved-portrait-and-autograph-1190>.

- Gefilte fish emblem: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/60/Gefilte-Fish-Car-Emblem-(2220)-1-.jpg. 23 Feb. 2011.

This post was made possible with the support of the Oregon Humanities Center, where I am currently Ernest G. Moll Faculty Fellow in Literary Studies. It grows out of my current book project, Double Diaspora in Sephardic Literature 1200-1600.