Catalan author Ramon Llull’s Blaquerna (late thirteenth century) is the story of a Christian monk whose path to spiritual perfection takes the shape of a knightly romance. Just as the knight errant goes from one military challenge to the next, all the while gaining in power and prestige, the hero of Blaquerna ascends the spiritual ladder from monk to papacy, all the while pursing his goal of converting the infidel and saving the souls of all Europe. It is a great example of how medieval Iberian authors put fiction to work promoting ideologies of crusade and conversion in a specifically Iberian context. Blaquerna is the novel of ideas for his theories of missionizing and conversion. In it he repeats in fictional form the ideas he first put forth in his crusader writings such as Liber de fine. In Blaquerna, Llull lays his plan for universal missionary crusade in a novel patterned after the chivalric novels of the crusader age in which he advocates for an ambitious, military-backed program of forensic crusade that would bring all of Islam, and the pagan nations as well, into the Church.

A missionary strategy for Iberian crusade

By the end of the thirteenth century it had become clear that the crusades as they had been imagined since the end of the eleventh century were not going to result in a Christian Jerusalem. Louis IX’s failed campaigns to Egypt and Tunis were from the start a compromise that had more to do with demonstrating piety and securing trade routes than actually winning Jerusalem. Crusading had become an important institution in Western Christendom whose utility went far beyond the romantic goal of a Christian Jerusalem. Correspondingly, while the idea and image of an Eastern crusade persisted in art and literature, it was no longer a military or political goal taken seriously at the highest levels. However, the relative success of the Christian conquest of al-Andalus had an important impact on the crusader imaginary of the thirteenth century. The crusades in Iberia were going far better than those in the East. This was good news for the Iberian military orders, whose participation in the conquests laid the foundation for the Iberian Christian political order.

Conversion of the infidel was not until the thirteenth century an important feature of the crusading project. From Urban’s first sermon’s preaching the First Crusade up until the middle of the twelfth century there are no voices calling for the conversion of Muslims and Jews, but rather for their annihilation, banishment, or at best, exploitation as subject minorities. This may be simply because the societies where the crusader movement emerged had no significant experience missionizing subject Jews and Muslims. However, as Christian kingdoms conquered more and more of the formerly Andalusi territories of the Iberian Peninsula, this situation began to change.

The Iberian crusader imaginary

What was this Iberian contribution to the crusader imaginary? How did the Iberian experience transform the idea of crusading from its beginnings in France? The conquest of al-Andalus resulted in Christian kings ruling over substantial Muslim and Jewish minorities, creating massive captive markets for the missionary work of the Dominican and Franciscan orders who had, over the course of the thirteenth century, become increasingly important players on the spiritual and religious stage of Christian Iberia. Once the sword had done its work, it was time for the cross to take over. It was this social reality of massive missionary ambition that produced a new strain in crusading fiction on the Peninsula: missionary crusade, a crusading ideal whose goal was not only to conquer, but to convert as well.

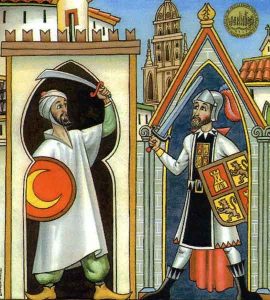

Ramon Llull’s Blaquerna is a kind of chivalric novel remade in a spiritual, missionary key. It substitutes spiritual and theological values for chivalric and courtly ones The hero excels in faith, devotion, and works. His swordsmanship is lacking. He defeats enemies by preaching to them. His goal is to convert the entire world to Christianity, to lead by example, and to draw the infidel to Christianity through reason, debate, and logic. Blaquerna’s crusade comes not only with a sword, but also with a syllogism.

Blaquerna is the fictional component of Llull’s grand ideological and intellectual program of crusade and mission. His Ars magna (Great Art) is the engine of conversion, the science that has the potential to unlock the minds and therefore the hearts of the unbelievers. The Liber de fine (Book of the End) and other crusade treatises are meant to mobilize political will and resources among the Church, the nobility, and the crown. The Llibre de l’ordre de la cavalleria (Book of the Order of Chivalry) is a training manual for the knights entrusted with enforcing Christian rule and setting the stage for the missionary to move in and close the deal. But the matador in this bullfight is the philosopher-preacher, who armed with Llull’s Ars, accomplishes with syllogisms in this new era of missionary crusade what the Templar and the Knight of St. James once accomplished with the sword: the conquest of the souls.

The Missionary Knight Crusader

Llull expounds this vision of the spiritual role of the knight in his Llibre de la orden de la cavalleria, in which he describes the knight as a kind of armed religious, a fitting ideology for the crusading age (Fallows 2). Following the doctrine of crusader as pilgrim that goes back at least to the sermons of Urban IX preaching the first crusade, the crusader knights, “cross the sea to the Holy Land on pilgrimage and take up arms against the enemies of the Cross.” (Van los cavalers en la Sancta Terra d’Oltramar en peregrinació, e fan d’armes contra los enamics de la creu) (Llull, Order 71; Llull, Cavalleria 208, 6.4). Just as the clergy upholds the faith with words, so does the knight with the sword. Here the sword (itself conveniently shaped like a cross) substitutes the cleric’s cross as instrument of Christ’s will on earth:

Just as our Lord Jesus Christ vanquished on the Cross the death into which we had fallen because of the sin of our father Adam, so the knight must vanquish and destroy the enemies of the Cross with the sword.

Enaxí con nostro senyor Jesucrist vensé en la creu la mort en la qual érem caüts per lo peccat de nostro pare Adam, enaxí cavayler deu venscre e destruir los enamics de la creu ab l’espaa (Llull, Order 66; Llull, Cavalleria 201, 5.2).

Blaquerna transforms the knightly ideal of epic and Arthurian Romance under the twin influences of thirteenth-century crusading and of Llull’s specific vision of the role of the knight in the later age of crusade after the fall of Jersualem. This missionary chivalry, based as it is on the weapon of disputation and on learning, displays a sophisticated understanding of Islamic doctrine, which is hardly surprising coming from Llull, who in his autobiography relates having spent years learning Arabic for this very purpose.

Benedicta tu in mulieribus. Pere Serra, Altarpiece, Monastery de Sant Cugat, ca. 1390. (Source: Wikipedia)

The Knight of Mary against the Saracens

Llull demonstrates this knowledge in an episode in which Blaquerna converts a knight itinerant he encounters to the cause of the Virgin, inducting him into the chivalric order Benedicta Tu, a reference to the Angel Gabriel greeting Mary in Luke 1:28: Benedicta tu in mulieribus (Blessed art thou among women).

In imitation of Arthurian knights who challenge all comers in defense of their lady’s nobility, the knight travels to the court of a Saracen king, intending to convert him and his subjects to Christianity. He challenges the King and any knight of his court to single combat. The king refuses, citing his belief (correct according to Islamic doctrine) that

Our Lady was [not] Mother of God, but that he believed indeed that she was a holy woman and a virgin and the mother of a man that was a prophet.

Nostra Dona [no] fos mare de Deu, mas be crehia que fos dona santa e verge, mare de home profeta (Llull, Blaquerna 253–254; Llull, Romanç 294, II.64.14)

The king refuses to meet the knight in combat and suggests instead that they dispute the matter. Nonetheless, the missionary knight of the order of Benedicta Tu demands single combat because he lacks the education necessary to engage in formal debate with the Saracen king, who eventually agrees to have his champion fight the Christian. The Christian knight fights the Saracen to a standstill, and they continue the next day, at which point the Saracen finally converts, provoking the rage of the Saracen king, who has both knights executed:

So they became martyrs for Our Lady, who honoured them with the glory of her Son, because for her sake they had suffered martyrdom. Even so she is ready to honour all those who in like manner will do her honour.

Aquells foren martirs per Nostra Dona, qui los honrá en la Gloria de son Fill per ço cor per ella a honrar havien pres martiri; e está aparellada de honrar tots aquells qui per semblant manera la vullen honrar” (Llull, Blaquerna 255; Llull, Romanç 295, II.64.16)

Here Llull again deploys a well-known trope from the chivalric literature of the day: the knightly challenge to his opponent to admit the supremacy of his lady or face single combat. Instead of championing his damsel, he champions the virgin, and just as the vanquished knight of a chivalric romance must on his honor concede to the supremacy of the victor’s beloved above all other women, here he must pledge fealty to the Virgin. This challenge (of course) proves irresistible, and the Saracen, defeated in single combat, submits to the supremacy of the Christian knight’s lady by converting to Christianity.

The conversion of this Saracen knight vividly puts into practice Llull’s brand of spiritualized and intellectualized chivalry by which he places the chivalric ideal of service to one’s lady squarely in service to the Church, substituting the Virgin for the knight’s earthly beloved.

Works Cited

- Fallows, Noel. “Introduction.” The Book of the Order of Chivalry. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: The Boydell Press, 2013. 1–33. Print.

- Llull, Ramon. Blanquerna: A Thirteenth Century Romance. Trans. E. Allison Peers. London: Jarrolds, 1926. Print.

- —. Llibre de l’orde de cavalleria. Ed. Albert Soler i Llopart. Barcelona: Editorial Barcino, 1988. Print. Els Nostres clàssics. Col·lecció A volum 127.

- —. Romanç d’Evast e Blaquerna. Ed. Joan Santanach and Albert Soler. Palma de Mallorca: Patronat Ramon Llull, 2009. Print.

- —. The Book of the Order of Chivalry. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: The Boydell Press, 2013. Print.

This blog post is part of a larger, book length project on Iberian crusade literature tentatively titled Spanish Crusade Fiction.