This entry is based on a public lecture I gave at the NYU Abu Dhabi Institute in NY on 29 October 2013 [link to video]. My thanks to Hilary Ballon, Deputy Vice Chancellor of NYU Abu Dhabi, Prof. Zvi Ben-Dor Benite of NYU Department of History, and Prof. S.J. Pearce of NYU Department of Spanish and Portuguese for the invitation and for their hospitality in NY.

This lecture is dedicated to the memories of two recently deceased teachers and colleagues, Prof. Samuel Armistead and Prof. María Rosa Menocal, both of whom paved the way. Que en Gan ‘Eden estén, may they rest in peace.

Tonight I am going to talk about the role of literature in cultural exchange in one interesting —but not unique— cultural moment in a part of the world that was at once of the cultural capitals of the Islamic world and a very important religious center of Western Christianity. Most of us think of the Iberian Peninsula as the point of embarkation of Columbus and Cortés, or as the site of a bloody civil war in the 20th century. Tonight I would like to take you back before all of this, to a time when Europe had yet to set its sights on the New World, before modern nation states and national languages and national cultures.

Like much of the world, the lands that are now Spain and Portugal were always a crossroads of different ethnic and linguistic groups. The people who are now known as the Basques migrated there during the mists of prehistory. Celts navigated their way across the Bay of Biscay and established colonies on Spain’s northern coast thousands of years ago, mixing with local Iberian tribes. Phoenicians established trading posts in southern cities such as Cadiz and Málaga well over two thousand years ago. The Romans pacified the Peninsula during the third to second centuries BCE, giving it the name Hispania, and its Romance languages, several of which are still spoken today. Visigoths came over the Pyrenees after the disintegration of Roman political power and installed themselves in Toledo, where they ruled over Hispania for over two centuries. In the eighth century CE, Muslim forces crossed the Straits of Gibraltar from Africa and in short order pacified the entire Peninsula. From 711, there would be Muslim kings parts of the Peninsula until Boabdil, King of Granada, lays his arms at the feet of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabel the Catholic in 1492. From a European perspective, this period of Muslim political dominance is what most distinguishes the history and culture of the Iberian Peninsula.

The Muslims who conquered and settled the Iberian Peninsula — overwhelmingly North African Berbers with a sprinkling of Eastern Arab élites— created a society that has no peer in Western Europe in terms of its multiconfessionality, its coexistence of the three major Abrahamic traditions.

Al-Andalus was a unique case in Western European history. Nowhere else in Western Europe was Islam the state religion and Arabic the state language for significant periods of time. Consequently, there is nowhere else in Western Europe, until very recently, where Muslims, Jews, and Christians, lived and worked together under a political system that espoused —but did not always adhere to— a doctrine of religious tolerance. I am referring to the Islamic doctrine of dhimma, the concept that the non-Islamic Abrahamic religions, Christianity and Judaism, were considered fellow Ahl al-kitab, ‘People of the Book,’ and as such are granted religious freedom and protections from persecution. This is a unique fact in the history of Western Europe. The only other case is that of Islamic Sicily, which was a far shorter time period and which left a very interesting, but ultimately shallower historical footprint.

I want to be very clear that I am not talking about a Golden Age of Tolerance here. Laws are one thing and people are another. We do not always respect doctrine. There was sectarian violence in al-Andalus, and the protections granted to Christian and Jewish religious minorities were a far cry from what we would expect in a modern democracy. They were not considered the equals of their Muslim counterparts. They paid a poll tax and were barred from occupying certain positions in government. However, they enjoyed the right to practice their religions, to organize and govern their own affairs autonomously, provided they did not offend Islam or Muslims in doing so.

This legacy of tolerance, while no utopia, was a significant historical fact and that made the examples I am about to discuss possible, at a time when religious minorities elsewhere in Western Europe fared considerably worse on the whole. What’s more, the material culture of al-Andalus far surpassed that of the rest of Christian Europe.

The Andalusi capital, Cordoba, in the tenth century boasted lit streets, public baths, and vast libraries when Germany and France were in the depths of what we like to call the Dark Ages. European visitors to the Caliph’s court in Cordova were flabbergasted by the luxury and cultural refinement they encountered there. To be sure, this was not the daily reality of all Andalusis, but when we talk about al-Andalus we should think of fifteenth-century Florence in terms of wealth and cultural refinement. To this day “al-Andalus” in the Arab world means ‘wealth, opulence, and artistic refinement and is used heavily in branding things like shopping malls and hotels.

Today as I’ve said I’d like to show you how this period of cultural wealth and relative tolerance found expression in literature, in a series of five examples that span as many centuries, some from a context of Muslim government and some from Christian kingdoms.

The city of Cordova in the tenth century was home to the court of the Umayyad Caliphs and the most populous, most technologically advanced, and wealthiest city in Western Europe. It was also a city where Classical Arabic was the official language of government and of state religion, of the literary establishment and of high culture. But it was not the only language spoken or written by Andalusis. Christians, Muslims and Jews spoke colloquial Andalusi Arabic and a dialect of Latin we’ll call Andalusi Romance. Jews prayed and wrote in Hebrew in addition to Classical Arabic. So the linguistic reality in al-Andalus at this time is one of widespread bilingualism both in spoken and in written language.

Andalusi poet singing, from Bayad wa-Riyad, 13th century, one of three surviving illustrated manuscripts from al-Andalus

Our first example is drawn the poetry of the court, and represents a striking innovation in the kind of songs that Andalusi poets recited and sang. We should remember that poetry, and “fancy” poetry of the type one might hear at court served a very different purpose in the tenth century than it does for us in the US in the twenty first. Poetry was political propaganda, it was a means to celebrate or revile public figures, it was a way to celebrate a victory or commemorate an important event. Poets created political and social capital in the images and catchy but authoritative phrases they coined. People repeated and recited the most memorable lines in daily discussion and in public and private gatherings. More than just a rarefied art form that one studied in school or that a select group of elite read quietly to themselves, poetry was more like a high-profile medium that traveled from mouth to mouth rather than from smartphone to smartphone.

Until the tenth century, when a poet performed a composition at court he recited it in a singsong voice, in metered monorrhyme lines; that is, every line in the poem ended in the same syllable. There may have been some musical accompaniment but poems were not sung to a melody, they were declaimed, recited.

According to tradition, in the middle of the tenth century, a blind poet named Muqaddam from the town of Cabra near Cordova, made a simple yet radical innovation in Classical Arabic poetry: he wrote poems that were meant to be sung, even danced to. In place of the traditionally metered monorrhyming verses, his songs, written in the same Classical Arabic as the Qur’an itself, were sung to popular tunes, had the variable rhyme scheme and stanza/refrain structure that is still so well known to us from today’s popular music. This was nothing short of revolutionary, a shocking innovation in Arabic poetic tradition.

Even more shocking was the fact that this Muqaddam included bits of these popular tunes in his compositions, tunes sung in not in the exalted language of the Qur’an but rather in the colloquial language of the street, the fields, and the marketplace. The listener would hear the orchestra’s introduction, and soon beneath the classical instrumentation and arrangements would hear the oddly familiar tune of a popular love song, over which the poet would sing in the language of the Qur’an, in formal metaphors and images drawn from classical tradition. And then, at the poem’s end, almost as an afterthought, the last lines became that popular tune itself. The effect was something like hearing a Shakespeare sonnet sung to the tune of a Shakira tune, and then hearing a verse from the Shakira tune at the end, at which point you realize that the sonnet has not just the same tune, but the same theme, and rhymes with the popular song.

I’d like to play you an example of this kind of poem or song by Ibn Zuhr, who was born in Seville in the eleventh century. His song ma li-l-muwallah is a festive bachanal set to popular music. This recording is a modern reconstruction by the Altramar Medieval Music Ensemble from their album titled Iberian Garden.

Muqaddam’s style of poetry became known as the muwashshah, or girdle poem because the individual stanzas were linked together by the refrain as if in a chain or woven belt. Singers in the Arab world still sing muwashshahat in Classical Arabic, most notably the iconic Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum. The classical Andalusi musical style still has large audiences in the cities of North Africa, many of which have their own Andalusi orchestras such as this one pictured in Tangiers, Morocco.

Nonetheless, the Andalusi muwashshah was an innovation built on cultural exchange, on crossing boundaries. By brining colloquial Arabic and Andalusi Romance language and popular melodies into the arts of the court, the poets of al-Andalus transformed both the popular lyrics they used as the basis for their learned compositions as well as the idea of what it meant to perform poetry at court.

Nonetheless, the Andalusi muwashshah was an innovation built on cultural exchange, on crossing boundaries. By brining colloquial Arabic and Andalusi Romance language and popular melodies into the arts of the court, the poets of al-Andalus transformed both the popular lyrics they used as the basis for their learned compositions as well as the idea of what it meant to perform poetry at court.

Jewish Andalusi poets carried this exchange a step further by adapting the new poetry into Hebrew. This, too represented a bold innovation in Hebrew poetic tradition on more than one count. First, it opened up Hebrew poetry to a vast range of ideas, imagery, thematic material, and technique that were previously the province of Arabic. They wrote Hebrew poetry using the language of the Hebrew Bible describing the themes and images of the Classical Arabic poetic tradition. The beloveds described in terms of gazelles or fawns, the lush descriptions of gardens, the metaphors drawn from desert life of the pre-Islamic Arabic poets all of this they recast in biblical Hebrew, sometimes in entire phrases lifted directly from the prophets, the psalms, the narratives of genesis and kings, and especially the Song of Songs or Song of Solomon.

These were also set to Andalusi classical arrangements, and to this day there are artists such as Rabbi Haim Louk who continue to interpret the Andalusi Sephardic tradition. Here is a short clip from his recent arrangement of a piyyut or devotional poem by the eleventh century poet Solomon ibn Gabirol. Rabbi Louk has set the poem to the tune of a very popular qasidamade popular by the Moroccan singer Abdesedek Chekara, who lived in the twentieth century.

Soon after the time of the poets Moses ibn Ezra and Ibn Zuhr, the balance of power on the Iberian Peninsula began to tilt in the direction of the Christian states in the north.

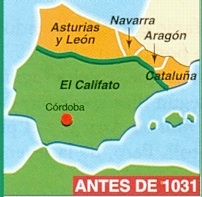

Asturian Christians from north of Cantabrian mountains began to push Muslim armies back onto the plains in the ninth century, during the days of the Umayyad Caliphate, and by the middle of the tenth century they had conquered large sections of the central plains, where they established their capital in León. Some fifty years later the Caliphate disintegrated, leaving in its wake a collection of petty Muslim kingdoms that competed with each other and with the Christian states to the north for dominance. The Christian kings of Leon and Castile pressed their advantage and by 1076 they had conquered Toledo, the former capital of the Visigothic kingdom. However, it would be another century and a half before the tide turned decisively in favor of the Christians. Historians view battle of Navas de Tolosa in 1212 the key date after which (at least retroactively) the writing was on the wall for al-Andalus.

Not coincidentally it was around this same time that Christians in Western Europe began to compose serious literary works in the various Romance languages they spoke, carving out space once occupied by their classical language, Latin. This was happening in neighboring countries as well, where increased commerce and the proliferation of universities spurred literary innovations that eventually gave Western Europe its Chaucers and Dantes. In Spain, however, Christian authors worked in the shadow of the considerable intellectual legacy of al-Andalus long after the balance of power on the Peninsula had turned in their favor. What this meant is that literary prestige in Christian Iberia was determined not only by imitation of Latin and French models but by the appropriation and translation of the massive corpus of Arabic-language learning that was produced in al-Andalus by the Christian kings’ Muslim predecessors.

The most famous example of this process was the court of Alfonso X, known as ‘The Learned’, who ruled Castile and León during the second half of the thirteenth century. His father was Ferdinand the Third, the Saint Ferdinand who gave his name to the San Fernando Valley in Los Angeles. You can still see his legacy in the city seal of LA.

If you look closely, beside the Mexican eagle and serpent and under the California bear, you can see a Castle and a Lion, the arms of the Kingdom of Castile and León. However, he was even more famous for having conquered the two most important cities in the south of the Peninsula, Cordova and Seville, in the middle of the thirteenth century.

After Ferdinand completed his considerable military conquests, all that was left of the great al-Andalus was the small Kingdom of Granada in the south, which was reduced to the status of client state to Castile and Leon, and remained a harassed tributary state until its eventual defeat in 1492 by the Catholic Monarchs Isabel the Catholic and Fernando of Aragon.

Such was the political landscape when Ferdinand’s son Alfonso X took the throne in 1252. Unlike his father, Alfonso was not a successful military leader and did not continue to expand his father’s territory. However, Alfonso’s contributions in the areas of science and letters equaled the accomplishments of his father in the military and political arena. Alfonso was the architect of a massive literary project that accomplished two important goals. The first was to establish and exalt Castilian as a literary language, displacing Latin as the most prestigious, most important language of learning at court. He commissioned an impressive corpus of works on law, science, official history, and philosophy, and statecraft that, in the space of a single generation, established Castilian as a prestigious literary language when Italian and French were just getting off the ground as such.

One of the ways Alfonso accomplished this was through translations of Arabic works directly into Castilian. Alfonso employed a team of scholars who translated scores of crucial works of science, philosophy, and wisdom literature into Castilian from Arabic. Just as his father Ferdinand claimed the great cities of al-Andalus for Christian Iberia, Alfonso’s aim was to lay claim to the intellectual tradition of al-Andalus, to reproduce in Castilian the curriculum that produced the great scholars of al-Andalus.

This was only a part of the Castilian vogue for all things Andalusi. The victorious Christian court consumed Andalusi textiles, music, architecture, and material culture with an enthusiasm rivaled only by its hunger for Andalusi learning. This transfer of Andalusi intellectual culture to the Castilian court was a forerunner of the European Renaissance, a flowering of Greek science and learning delivered by the conduit of Andalusi civilization.

As a result, Alfonso’s court was arguably the most sophisticated, most technologically advanced court in Western Christendom, which, in his estimation, made him worthy of the title of Holy Roman Emperor. He never achieved this honor, but what he did do was make available in the vernacular language of the court, a massive library of high-tech and cutting edge works of mathematics, astronomy, natural sciences, philosophy, and most important for our discussion this evening, literature.

In 1251 Alfonso commissioned a translation of the classic Arabic work of gnomic narrative, Kalila wa-Dimna or ‘Kalila and Dimna.’ The book is a collection of exemplary tales, similar in structure to the 1001 Nights, told to a Lion king by two courtiers, jackals, one named Kalila and the other Dimna. This way of telling stories, these stories within stories, came to Arabic from Indian tradition and dates back to at least the first century CE. As we will see, through the Alfonso’s translations this tradition reached Europe and provided one of the inspirations for the modern novel. In Kalila wa-Dimna, The jackals told stories that provided political advice to the lion, and was a form of manual for political survival in narrative form, akin to the ‘Mirror of Princes’ genre cultivated in Western Europe in Latin. In many of the exemplary tales contained in the book, the main characters are discussing a political problem faced by the Lion king, and Kalila or Dimna offer advice in the form of a story that illustrates the way to control the situation.

This model of telling stories introduced to the nascent vernacular literature by Alfonso the tenth, became a vogue in Europe and were widely and successfully imitated. Giovanni Boccaccio borrowed the idea for his Decameron, a collection of tales told to each other not by advisors and kings but to a group of Florentine courtiers fleeing an outbreak of plague in the countryside. Geoffrey Chaucer followed suit in his Canterbury Tales, his collection of stories told by a group of pilgrims traveling from London to Canterbury. Both of these examples leave the courtly setting and political context behind but in both cases the stories are a bulwark against some danger, not the intrigue and political hijinx of the royal court but the lurking danger of plague, or the perils of the medieval English highways.

This tradition of appropriating Andalusi learning and material culture became the prestige model for courtly culture in Castile. For centuries, Castilian nobles were avid consumers of Andalusi textiles, architecture, ceramics, food, and music. This phenomenon was difficult to characterize. Were these Castilians simply cynically aping and appropriating the culture of the civilization they had essentially defeated and with whom they were sporadically at war for as long as they could remember? Or was Andalusi culture part of Castilian culture? Politically it was clear that Castile was a Christian kingdom, but it was one that counted many thousands of Andalusi Muslims, Jews and Christians in its population. Some cities remained essentially Andalusi in their cultural life for centuries after being conquered by Christian armies. In Toledo, for example, Arabic was used as one of the classical languages of the Mozarabic Christian community, the descendents of the Christian community of Andalusi Toledo. Though that city was, as we have mentioned, conquered by Castile in 1070 CE, Mozarabic scribes continue to file land deeds and other documents written in Arabic for over three centuries. In the Crown of Aragon, the city of Valencia, conquered by Aragon in the early thirteenth century, continued to be a center of Andalusi culture and a vibrant Arabic-speaking community for over two hundred years. Politics and religion aside, it was sometimes difficult to say where al-Andalus ended and Castile began.

This tradition of appropriating Andalusi learning and material culture became the prestige model for courtly culture in Castile. For centuries, Castilian nobles were avid consumers of Andalusi textiles, architecture, ceramics, food, and music. This phenomenon was difficult to characterize. Were these Castilians simply cynically aping and appropriating the culture of the civilization they had essentially defeated and with whom they were sporadically at war for as long as they could remember? Or was Andalusi culture part of Castilian culture? Politically it was clear that Castile was a Christian kingdom, but it was one that counted many thousands of Andalusi Muslims, Jews and Christians in its population. Some cities remained essentially Andalusi in their cultural life for centuries after being conquered by Christian armies. In Toledo, for example, Arabic was used as one of the classical languages of the Mozarabic Christian community, the descendents of the Christian community of Andalusi Toledo. Though that city was, as we have mentioned, conquered by Castile in 1070 CE, Mozarabic scribes continue to file land deeds and other documents written in Arabic for over three centuries. In the Crown of Aragon, the city of Valencia, conquered by Aragon in the early thirteenth century, continued to be a center of Andalusi culture and a vibrant Arabic-speaking community for over two hundred years. Politics and religion aside, it was sometimes difficult to say where al-Andalus ended and Castile began.

Nowhere is this confusion more evident that in the work of Alfonso’s nephew, the powerful nobleman Don Juan Manuel, author of the collection of tales known as El Conde Lucanor, the tales of Count Lucanor. Juan Manuel was, after the king, the most powerful man in Castile. He was governor of the border state of Murcia, and had extensive diplomatic experience dealing with the kingdom of Granada. Like his uncle Alfonso, though perhaps not quite so prodigiously, he wrote a series of works of noble interest, ranging from his treatise on politics El Libro de los Estados, the ‘Book of the Estates’ to works on hunting and chivalry, to his most famous book, the Conde Lucanor. The structure of this collection of tales tells us the story of the continuing assimilation of Andalusi learning in the court of Castile and what intellectual and cultural fruits this process bore. Like Alfonso’s Kalila wa-Dimna, Conde Lucanor begins with a story about a ruler in need of advice. In Juan Manuel’s book this ruler is a member of the high nobility, but not a king, like Juan Manuel himself. His advisor Patronio responds to specific questions about real-life political predicaments posed to him by the Count. Don Juan Manuel takes the structure of Kalila wa-Dimna as a starting point, but transforms the animal fables and out-of-time-and-place anecdotes of the Arabic work into relatively realistic stories set in places like Cordova and Toledo. He gives his characters Castilian or Andalusi names and sometimes includes tales about historical figures from the region. He weaves together material drawn from folklore, from official histories, historical anecdotes, Latin manuals of materials for sermons written by Dominican friars, and tales from local oral tradition. Many of the stories in Conde Lucanor are also found elsewhere in other Latin or Arabic versions. In one famous case, he includes the tale of a wise magician and a foolish Churchman that is found in only one other source: a Hebrew book written in Castile in during the time of Alfonso X.

This tale and its transformations from Castilian folktale to the Hebrew literary work of Ibn Sahula to the Conde Lucanor of Juan Manuel provides us with another example of how literary materials and traditions move between religious and linguistic groups in medieval Iberia. A further example of Castilan literary innovation that was made possible by the translation work carried out by Alfonso’s teams is found in a curious book by the title of El libro del cavallero Zifar, ‘the Book of the Knight Zifar.’

Miniature of Zifar and Grima from Libro del Caballero Zifar (15th c. manuscript) (Bibliothèque Nationale Espagnol 36)

This book tells the story of a knight errant who in some ways might have been drawn from books about Arthur and Lancelot, but in other ways is a sort of frame character himself who serves as justification for the exposition of a large corpus of proverbial sayings and maxims drawn from Alfonso’s translations and other Eastern sources of wisdom literature. Like the Conde Lucanor, the Book of the Knight Zifar is the result of the second generation of the appropriation of Andalusi learning, the incorporation of Andalusi wisdom literature into the Arthurian Chivalric Romance. As such it is more than the story of a knight’s adventures; it is the story of the Castilian Christian appropriation of Andalusi learning and what that means for the culture of the court, projected onto the familiar literary figure of the knight errant.

Zifar is an exceptional knight who bears a most inconvenient curse that causes his horse to die every ten days. He is separated from his wife and children, is shipwrecked, falls in love with various women, and finally becomes king and is reunited with his family. The saga continues with the adventures of his second son Roboán, who embarks on a career of knight errantry whose narration is studded with proverbs, sayings, and philosophical musings, all with a very Christian moralizing yet Mediterranean cosmopolitan viewpoint. The chivalric qualities of the Zifar and Roboán are always described in terms of Christian values, and even graphic depictions of bloody combat are framed in terms of the theology of just war.

Some have argued that the book was itself translated from Arabic as part of the massive translation project of Alfonso the tenth. Many of the characters have names that may well be derived from Arabic words. Zifar himself may be loosely derived from the Arabic verb Safara, ‘to travel,’ which yields ‘safari’ in English. His wife Grima, maybe a corruption of the Arabic Karima, ‘noble, precious.’ Many of the place names are suggestive of place names drawn from medieval Arabic works of geography. The land that Zifar’s son eventually comes to rule, Tigrida, is located between the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers, in what we know call Iraq.

What is interesting about the “Eastern” features of the Book of the Knight Zifar is that they are largely window dressing. The conceit of translation from Arabic is an allegory for the transmission of learning from al-Andalus to Castile, a confirmation of the prestige of the Andalusi intellectual legacy, but not an actual exploitation of it. Here the exchange of learning from al-Andalus to Castile is framed not in terms of a manual of political dominance but in a fantasy of Christian morality and knightly excellence, with a sprinkling of statecraft similar to that found in Kalila wa-Dimna and Conde Lucanor. It is an allegory of the development of Castilian courtly culture in the wake of the Christian conquest of al-Andalus.

Thus we see that in the thirteenth century as in the twenty-first, novels and politically flavored fiction have as much to do with current events as they do with art and storytelling. In the cases of Don Juan Manuel’s Conde Lucanor and the anonymous Libro del cavllero Zifar, the authors tell their versions of the story of the the new, Christian-ruled al-Andalus. The winners tell story of what the intellectual culture of the Castilian court becomes, after enjoying the intellectual spoils of war, the Andalusi legacy of learning and science.

My last two examples this evening come to us from the minority cultures of Christian Iberia, and demonstrate a different type of literary cultural exchange. They are not about how the triumphant majority exploits and incorporates the learning of the vanquished, but rather how a minority culture makes use of the literary languages and building blocks of the dominant culture. I wish to demonstrate how the Muslim and Jewish subjects of these Christian monarchs made sense of the world in which they found themselves living, one in which they were not guaranteed the same institutional protections afforded to religious minorities in al-Andalus. While some Christian Iberian monarchs practiced certain forms of religious tolerance at certain times, there was no Catholic doctrine of tolerance to serve as a guide for political action. Consequently the fortunes of Castile’s Muslim and Jewish populations were dependent upon the whims of the monarch and upon the mood of the church, the nobility, and of the mob.

After the Christian conquest of al-Andalus, the fortunes of the Muslim populations of areas like Valencia and Murcia took a sharp turn for the worse. Rather than live under Christian rule as a religious minority, the ruling elites fled to Granada or North Africa, and the great majority of Muslims living under Christian rule were either tenant farmers or artisans. While most communities enjoyed the right to continue practicing Islam into the sixteenth century, there was a severe brain drain that cut the legs out from underneath institutional Islamic life in Christian Iberia, and began a long process of cultural deprivation that would become extreme in the years following the conquest of Granada.

The Capitulation of Granada, by Francisco Pradilla y Ortiz: Boabdil confronts Ferdinand and Isabella. 1882

1492, as you all know, was an important year for a number of reasons. We all know about the first voyage of Columbus, but it was also the year of the defeat of Granada, when the triumphant Catholic Monarchs Isabella the Catholic of Castile and Leon and Ferdinand of Aragon took possession of the Alhambra, thus ending the existence of Islamic political power in Western Europe. This military defeat by no means signaled the end of Islamic life in Christian Iberia. In fact, according to the Capitulaciones de Granada, the surrender treaty offered to Granada’s Muslim population by Ferdinand and Isabella, Granadan Muslims enjoyed very explicit protection of their religious freedoms, including the right to practice Islam, to organize the affairs of the Muslim community according to shari’a law, to educate their children in madrassat, and to enjoy representation at court, all in perpetuity:

Their highnesses and their successors will allow [all the people of Granada] great or small, to live in their own religion, and not permit that their mosques be taken from them, nor their minarets nor their muezzins. . . nor will they disturb the uses and customs which they observe. (Constable 345)

However, a decade after the fall of Granada the pious and severe Isabel had a change of heart, and reneged on the terms set out in the Capitulations. Under the influence of her confessor, the ambitious and zealous priest Fray Franciso Jiménez de Cisneros, the Catholic Monarchs prohibited the practice of Islam in 1502, and required all Muslims to convert to Christianity or quit the kingdom. These hastily converted and poorly catechized Muslims became known derogatorily as ‘Moriscos,’ little Muslim-ish new Christians, neither properly Muslim nor properly Christian.

This disastrous moment did not in any way, however, mark the end of Islam in Spain. Rather, it marked the beginning of a new phase of clandestine or crypto-Islam, a transformation of traditional Islamic life to the new straitened circumstances. The brain drain that resulted from the near total exile of Islamic elites from the peninsula meant that it became very difficult to receive formal instruction in Islamic religion, law, and even in the classical Arabic language. Although some crypto-Muslims in places such as Granada and Valencia continued to speak colloquial Andalusi Arabic, the new prohibitions eventually ensured that almost none had any real proficiency in Classical Arabic, and even fewer were able to compose original texts in the language. Once Philip the Second prohibited the Arabic language itself in 1567, it became extremely dangerous to have any book written in Arabic in one’s possession. This applied equally to works of poetry, law, history, or fiction as it did to the Qur’an and its commentaries. By the middle of the sixteenth century, just as the struggles between Catholics and Protestants were reaching a fever pitch on the European continent, Islam went underground in Spain.

The end of publicly organized Islamic life during the period did not mean the end of Islamic cultural practice or even of Islamic literature in Spain, however. Spanish Muslims continued to smuggle books from Granada and North Africa into Christian realms, but given the near total death of Classical Arabic studies, the distribution and consumption of Islamic texts underwent a curious transformation. Moriscos began to adapt classical texts on Islamic topics into Spanish, the only language that most Spanish Muslims were able to understand. And yet, though the Moriscos could not read Classical Arabic, they clung tenaciously to the Arabic alphabet, the letters in which the Qur’an was written, and wrote their Spanish-language religious treatises in the Arabic letters of the Qur’an.

So was born Aljamiado literature, written in Spanish using Arabic letters. It was called Aljamiado from the Arabic word `ajamiyya, the language of the `ajami, or non-Arabs. This was a term that had been applied throughout Islamic history to the vernacular languages of non-Arab Muslims, such as Farsi or Tamazigh (Berber). Like many writing systems, the Arabic alphabet had been adapted to write several languages of Muslim communities such as Farsi, Urdu, and even Uigur. Aljamiado literature was the only example of Muslims using the Arabic Alphabet to write in a Romance language.

Authors composed a wide variety of Aljamiado texts. The lion’s share are religious treatises, including basic primers and compendia of Islamic religious practice and thought. There are narrative poems and prose legends celebrating key figures from the Qur’an, devotional poetry, Qur’anic exegesis. But there is also an imaginative literature that includes exemplary tales, translations of the accounts of the epic battles of Islamic expansion, and even an Islamicized version of a popular romance novel, the Amores de Paris y Viana, the Romance of Paris and Viana. I’d like share with you briefly one remarkable example of this literature to illustrate the extent to which Islamic, Hispanic, and European traditions merge and interplay in the literature of late Spanish Islam.

Mohammad de Vera, Tratado de la creencia, de las prácticas y de la moral de los musulmanes, 17th century. (Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Espagnol 397)

The text in question is called La Doncella Carcayona, ‘The Damsel Carcassone’ and it is an Islamicized, Iberian version of a folktale that is told across Europe. There are versions recorded in French, Italian, Russian, and several other languages. It is the tale of the Maiden of the Severed Hands. The tale is a perfectly classic European folktale that contains many familiar motifs and characters known to us from the Grimm Brothers’ collection and other sources: the incestuous King, the magical talking helper animals, the gallant young prince who comes to the aid of the damsel in distress. There is even a wicked mother-in-law, here standing in for the wicked stepmother made famous by Cinderella. And yet, this at the same time a perfectly Islamic folk tale. The author has pressed the tale of the maiden of the severed hands into service as a primer for Islam. The entire point of the story is to demonstrate the powers of Islamic faith and daily prayer.

This version was written in Tunis by a Morisco who had arrived there after the expulsion from Spain in 1613. Our anonymous author wrote this text in Roman characters, a testimony to the extent to which many Moriscos had been almost completely Hispanized and were full participants in the vernacular culture shared by Christians and Muslims.

This damsel Arcayona followed the religion and idolatry of her father, and had a beautifully fashioned silver idol that she worshipped. And, one day, while this damsel was praying to her idol, she sneezed. When she invoked the name of her idol an angel appeared, in shape of a beatiful dove, on top of the head of the idol. The dove spoke to her in clear and measured speech:

¡Ya damsel! You must not continue to do that, but rather say alandulilah arabin allamin

And, just as the angel said this, the idol fell to the ground.

What in a secular European folk tale would be attributed to magic is here attributed to the power of God. The enchanted dove is in fact an angel who (elsewhere in the story) teaches Carcayona the shahada, the Muslim credo or affirmation of faith, demonstrating the power of faith to carry one through difficult times; a fitting lesson for a religious minority that suffered terrible persecution in Spain and an uncertain future in North Africa.

This remarkable literary hybrid demonstrates very clearly that coexistence and cultural sharing is not always an expression of a positive experience or of a tolerant and peaceful society, but that adversity also breeds innovation across traditions. Hopefully these examples can teach us lessons about how different traditions can coexist fruitfully.

The same year in which Granada fell to the Catholic monarchs was also the year in which they decided to expel the Jews from their kingdoms. Like the decision to put and end (or at least try to put an end) to Islam, this catastrophic event gave rise to some significant cultural formations that, like the phenomenon of Aljamiado literature, demonstrate great adaptability and resilience.

I am speaking here of the culture and language of the Sepharadim, the exiled Spanish Jews, who, once settled in their new homes in North Africa, the Ottoman Empire, or elsewhere, continued to speak Spanish, sing the ballads they had learned growing up in Spain, and wrote in Judeo-Spanish to the present day. The Sephardic Jewish communities in the Ottoman Empire became, somewhat ironically, a vibrant center of Spanish culture in the heart of Spain’s rival superpower in the Mediterranean, a sort of anti-Spain within Ottoman Constantinople or Smyrna.

Since before the days of al-Andalus, Spain’s Jews had always spoken the vernacular languages of the majority. Hebrew for them was a classical language that was used for prayer, religious study, legal records, correspondence, and was occasionally pressed into service with other Jews as an international lingua franca much the way that Latin was sometimes used among literate Christians. However, there were no toddlers speaking Hebrew in Spain, and Spanish Jews, like their Christian and many of their Muslim counterparts, grew up speaking Spanish or Portuguese or Catalan, singing the same traditional songs, and telling the same stories as their Christian neighbors. Within their community, certain linguistic habits began to develop: key concepts or words from religious practice or formal Hebrew discourse made their way into everyday speech, such that the Hebrew ben adam, literally ‘person’ was (and still is) used to mean “anyone” alongside the Spanish fulano, itself, it is worth pointing out, a loan from Arabic. Likewise certain Hebrew words acquired Spanish grammatical features and were so incorporated into Judeo-Spanish, such as the word amazalado, or ‘lucky’, which is patterned after the Spanish afortunado, ‘fortunate,’ but based on the Hebrew word mazal, ‘good fortune, luck,’ which one often hears among contemporary Jews: mazal tov, or literally ‘good fortune,’ but meaning ‘may you continue to enjoy good fortune.’ This type of finely grained exchange is another example of how closely intertwined the various traditions of the Peninsula had come to be by the late fifteenth century, despite —or perhaps due to— the political and sectarian tensions that characterized the fifteenth century in the region.

Since before the days of al-Andalus, Spain’s Jews had always spoken the vernacular languages of the majority. Hebrew for them was a classical language that was used for prayer, religious study, legal records, correspondence, and was occasionally pressed into service with other Jews as an international lingua franca much the way that Latin was sometimes used among literate Christians. However, there were no toddlers speaking Hebrew in Spain, and Spanish Jews, like their Christian and many of their Muslim counterparts, grew up speaking Spanish or Portuguese or Catalan, singing the same traditional songs, and telling the same stories as their Christian neighbors. Within their community, certain linguistic habits began to develop: key concepts or words from religious practice or formal Hebrew discourse made their way into everyday speech, such that the Hebrew ben adam, literally ‘person’ was (and still is) used to mean “anyone” alongside the Spanish fulano, itself, it is worth pointing out, a loan from Arabic. Likewise certain Hebrew words acquired Spanish grammatical features and were so incorporated into Judeo-Spanish, such as the word amazalado, or ‘lucky’, which is patterned after the Spanish afortunado, ‘fortunate,’ but based on the Hebrew word mazal, ‘good fortune, luck,’ which one often hears among contemporary Jews: mazal tov, or literally ‘good fortune,’ but meaning ‘may you continue to enjoy good fortune.’ This type of finely grained exchange is another example of how closely intertwined the various traditions of the Peninsula had come to be by the late fifteenth century, despite —or perhaps due to— the political and sectarian tensions that characterized the fifteenth century in the region.

As in the case of Aljamiado, Judeo-Spanish was and continues to be a distinctively Jewish form of Spanish. Judeo-Spanish or Ladino is a base of medieval Spanish that over time acquired many loan words from Hebrew, Arabic, Turkish, Greek, Italian and French, but that retains even today a recognizably fifteenth-century grammar and vocabulary that is novel but intelligible to speakers of modern Spanish. In fact, it is a language that was spoken in this city, in fact in this neighborhood for many years. While the existence of a Yiddish press in New York is a well-known fact, there was also between the wars a very active and productive Ladino press.

One of the newspapers, La vara, a humor and political commentary weekly, published in Ladino had its offices right here on Rivington St., a neighborhood perhaps better known for its Yiddish legacy, but where you may currently hear plenty of Spanish spoken. The paper, in addition to running pieces of local and international interest to the Ladino-speaking community in New York, also advertised the services of local merchants and professionals, such as the “Dentista Español” Eli Hanania, who practiced, according to this advertisement, at 21 East 118th St. uptown.

This community flourished between the wars, and in the nineteen sixties still boasted members who knew by heart scores of ballads that their great great great grandparents had learned in Spain, and had carried with them for centuries in Morocco, and the Ottoman Empire. While Ladino has almost entirely ceased to be spoken as a natural language — you would be hard pressed to find a baby learning it from her mother today, there are a number of writers and musicians who continue to compose in Ladino and use it as a language of artistic and journalistic expression. Among them is the New York based singer Sarah Aroeste, a fragment of whose 2012 recording of “Scalerica de Oro,” a traditional Ladino song, you are about to hear.

This song, I believe, brings us full circle, from medieval Spain back to current day New York. I hope that through these examples you have some sense of the richness and variety of cultural exchange evident in the literatures and languages of medieval Iberia. I’ve prepared a handout for those of you interested in doing some further reading and of course I am very much looking forward to your questions now. Thank you.

Suggestions for further reading

For an overview of medieval Iberian literature, politics and culture in an accessible format, see the work of the late María Rosa Menocal: The Ornament of the World (Boston: Little Brown, 2002). You may also enjoy her coffee table book that includes a series of essays, photos and literary excerpts: Dodds, Jerrilynn Denise, María Rosa Menocal, and Abigail Krasner Balbale’s The Arts of Intimacy: Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Making of Castilian Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008). Also of interest is a recent volume of poetic texts from late medieval and Early Modern Iberia with accompanying English translations edited by Vincent Barletta, Mark Bajus, and Cici Malik: Dreams of Waking: An Anthology of Iberian lyric Poetry, 1400-1700 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013). Also quite interesting is Olivia Remy Constable’s anthology, Medieval Iberia: Readings from Christian, Muslim, and Jewish Sources (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997), which includes a broad selection of historical and literary documents from the period drawn from all the languages of the peninsula and translated into English. For a more encyclopedic and academic overview of the literatures and cultures of al-Andalus, see The Literatures of al-Andalus (Cambridge History of Arabic Literature), edited by María Rosa Menocal, Raymond Scheindlin, and Michael Sells (Cambridge: Cambridge Unversity Press, 2000).

On the Arabic poetry of al-Andalus, the bilingual Arabic-English anthology of James Monroe is essential: Monroe, James T. Hispano-Arabic Poetry: A Student Anthology. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974. Monroe’s landmark anthology has been recently reprinted by Gorigas Press and is easily available. For an overview of the history of al-Andalus see Richard Fletcher, Moorish Spain (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006) and Nicola Clark’s The Muslim conquest of Iberia: medieval Arabic narratives (London: Routledge, 2012).

Raymond Scheindlin has edited two volumes of bilingual Hebrew/English selections of the major Andalusi Hebrew poets, with explanatory notes for each poem. See Wine, Women, and Death: Medieval Hebrew Poems on the Good Life (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1986) and The Gazelle (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1991). More recently Peter Cole has published a large anthology of Hispano-Hebrew poetry with excellent translations of a wide variety of Hebrew poets from Spain, also with excellent notes and bibliography: The Dream of the Poem: Hebrew Poetry from Muslim and Christian Spain, 950-1492 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007). His volume of bilingual Hebrew/English selections of poetic texts from the Kabbalah tradition also contains a number of selections by Iberian authors: The Poetry of Kabbalah: Mystical Verse from the Jewish Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).

Chris Lowney includes a chapter on Alfonso X’s translation activity in his A Vanished World: Medieval Spain’s Golden Age of Enlightenment (New York: Free Press, 2005), as well as chapters on related cross-cultural issues such as Andalusi science, conversion, theology, and the Christian conquest of al-Andalus.

On the history of the Moriscos, see Matthew Carr’s very well-written and impeccably researched Blood and Faith: The Purging of Muslim Spain (New York: The New Press, 2009). For a more academic approach to the literature and culture of the Moriscos, see Vincent Barletta’s Covert Gestures: Crypto-Islamic Literature as Cultural Practice in Early Modern Spain (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005). The classic volume on Morisco history is Henry Charles Lea’s The Moriscos of Spain: Their Conversion and Expulsion (Philadelphia: Lea Brothers & Co., 1901) which has passed into the public domain and is available online free of charge from the Hathi Trust Digital Library (www.hathitrust.org). It has also been reprinted by Greenwood Press (New York, 1968).

For a popular history of the Sephardic Jews, see Jane Gerber’s The Jews of Spain: A History of the Sephardic Experience (New York: The Free Press, 1992). For a history more focused on linguistics and literature see Paloma Díaz Mas, Sephardim: The Jews from Spain (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992). Rabbi Marc Angel has published an excellent synthesis of Sephardic intellectual history: Voices in Exile: a Study in Sephardic Intellectual History (Hoboken: KTAV, 1991).

There is relatively little Ladino literature translated into English. Matilda Koen-Sarano has published two volumes of Sephardic folktales translated into English: King Solomon and the Golden Fish: Tales from the Sephardic Tradition (Detroit: Wayne State University Pres, 2004) and Folktales of Joha, Jewish Trickster (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2003). See also the more recent A Jewish Voice from Ottoman Salonica: The Ladino Memoir of Sa’adi Besalel a-Levi, edited by Aron Rodrigue and Sarah Abrevaya Stein, and translated by Isaac Jerusalmi (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012), and An Ode to Salonika: The Ladino Verses of Bouena Sarfatty, edited and translated by Renée Levine Melammed (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013).

On the Sephardic community in the United States see also his La America: The Sephardic Experience in the United States (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1982), and the more recent work by Aviva Ben-Ur, Sephardic Jews in America: A Diasporic History (New York: New York University Press, 2009), which contains ample documentation of the Ladino press in New York City.