The road to Sefarad (source: aviladaldia.com)

What is the role of Sefarad for medieval Iberian studies? One of the core concepts of Iberian studies as a field in challenging traditional Hispanism is to decenter Castilian and develop approaches that integrate texts, voices, and materials from the other linguistic traditions of the Peninsula. At the turn of the twenty-first century, specialists in premodern Hispanic studies began to issue calls to rethink the field in ways that made meaningful connections with the currents of thought that had been transforming Colonial and Latin American studies since the ‘theory revolution’ of the 1980s (Dagenais and Greer 2000; Fuchs 2003; Cascardi 2005). This emerging discussion of global Hispanism all but omitted the Sepharadim and conversos, whose study suffers a double marginalization in the field for being geographically and religiously outside the scope of most specialists in Hispanic studies. Jewish religion and Hebrew language do not typically form part of Hispanists’ training except among specialists in Sephardic or Latin American Jewish topics. Scholars working in the subfield of medieval Hispanism, however, took up the challenge of broadening the discussion and making room for the other medieval languages of the Peninsula.

María Rosa Menocal reminds us:

If unified nations and single national languages are the benchmarks for the divisions of literatures established in the modern period, then the medieval universe which precedes it cannot be fit into those same parameters and divisions, without distorting the past to make it seem as if its only lasting value was in laying the groundwork for a distant and ultimately unimaginable future (Menocal 2004a, 61)

In the same volume and in a similar key, John Dagenais calls for renewed attention to Sephardic studies under the umbrella of Iberian studies:

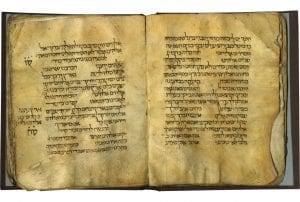

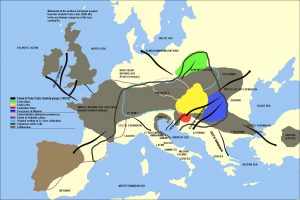

The remarkable flourishing of Sephardic culture, including numerous publications in Ladino, often using the Hebrew alphabet, in the centuries following the expulsion, as well as the survival today of hundreds of ballads whose origins can be traced back to late medieval Spain among the Jewish communities of North Africa, the eastern Mediterranean, the Near East, and the New World, give a shape to ‘medieval’ Iberian literature which defies not only the national and ethnic boundaries but also the temporal ones we might place upon it. It requires a rethinking, especially, of what such temporal boundaries mean. (Dagenais 2004, 54–55)

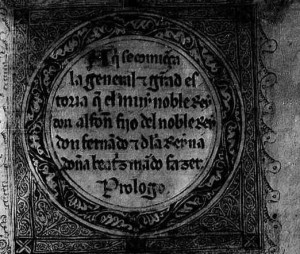

Manuscript 13th-century Spanish manuscript of the Psalms (source: www.textmanuscripts.com)

It is telling that Dagenais does not mention Sephardic Hebrew texts (as opposed to Ladino or the Castilian spoken and written by Jews and conversos): it is not, after all, a variety of Spanish, as is Sephardic Spanish. Menocal, on the other hand, was emphatic in emphasizing Hebrew as an Iberian language and advocates for scholars who do not read Hebrew and Arabic to rely on translations as a point of departure for further study and as a way to expand the scholarly discussion (Menocal 2004b, 159; Wacks 2008)

Iberian Studies is an emerging field that seeks to read the cultures of the Peninsula against the grain of national history and philology. The objective of an Iberian studies approach is to deprivilege the national ideas of Spain and Portugal and the institutions of Hispanism in order to try to make space for the voices we do not hear in a narrative that focuses on Catholic Castilian men writing in Castilian. In the preface to his 2013 volume Iberian modalities: a relational approach to the study of culture in the Iberian Peninsula Joan Ramon Resina highlights the discipline’s “intrinsic relationality and its reorganization of monolingual fields based on nation-states and their postcolonial extensions into a peninsular plurality of cultures and languages pre-existing and coexisting with the official cultures of the state” (Resina 2013, vii). In 2017, the editors of the Routledge Handbook of Iberian Studies, Javier Múñoz-Basols, Laura Lonsdale, and Manuel Delgado, write that they seek to create “a comparative space in which the much greater linguistic and cultural diversity of the Iberian Peninsula is the prime object of interest” (Múñoz-Basols, Lonsdale, and Delgado 2017, xxiii).

Categories? What categories?

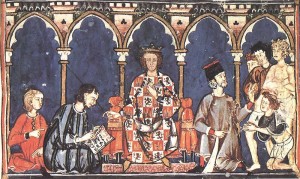

(source: www.cantigasdesantamaria.com)

Medieval Iberianists have been doing this work for years, thanks to the pre-national character of the societies we study. Medieval Iberians did not experience their world in the categories inherited by the nineteenth-century academics who taught us to write national literary histories, and there is no reason contemporary academics should hew to their example apart from mere conservatism or habit of thought.

However, in looking beyond Castilian, we may run some risk of observing national literary history in its breach. For example, if we recognize the existence of Hebrew, Arabic, and non-Castilian romance dialects but relegate them to the ‘kids’ table’ by ghettoizing them in their own respective chapters or subdisciplines (Greer 2006, 71), we have not made much progress. However, there is much we can learn by attempting to integrate Iberian Jewish voices into a broader vision of the cultural history of the Peninsula. Individuals and communities were often bilingual or multilingual; courts were most certainly; that of Alfonso X of Castile-Leon (r. 1252-1284) is the favorite example among Hispanists, but one could also mention the Caliph Abd al-Rahman III (r. 912-961) or Jaume I (r. 1213-1276) of Aragon as rulers of multilingual, multicultural courts. The producers and consumers of medieval Iberian literature did not see a given text as belonging to a national tradition. Rather, they were products of a particular person and a particular cultural moment whose context was usually more complex than we make it out to be today. Furthermore, studying a cross-section of Iberian linguistic traditions together provides us a richer context for studies of individual authors or texts, in any language or religious tradition. As Brian Catlos has written in his discussion of Mediterranean culture, “developments that seem anomalous, exceptional, or inexplicable when viewed through the narrow lens of one religio-cultural tradition, suddenly make sense when viewed from the perspective of a broader interconnected and interdependent [system]” (2017, 14). Developments in Jewish Iberian culture are often part of broader Iberian or Mediterranean currents across religious groups and languages.

The study of Sefarad as an idea or field of cultural practice has much to offer and enrich Medieval Iberian studies. More than just the study of a ‘minority culture’ that thrived within Andalusi or Christian societies, it is a different lens through which to view the world: if Hispanism sees the medieval Iberian world through Castilian, Christian eyes, and takes as its center the courts of the kings of Castile-Leon, the study of texts and cultural practices of Jewish Iberians see the world through two lenses: the Jewish and the Sephardic. It is a sort of double consciousness (Du Bois 1989, 3) by which Sepharadim see themselves both as Jews constituted within a Jewish symbolic order, and on the other hand see themselves reflected as dhimmi or Jewish subjects of Muslim or Christian majoritarian cultures.

Sacrifice

(source: cojs.org)

Judaism as a culture developed a vision of the world with the Biblical world at the center, predicated on the memory of a pre-exilic Israelite political order, with the rabbis as “substitute kings” (Biale 1986, 45). In diaspora, this political order transformed into a series of metaphors, by which the power of sovereign institutions that no longer existed (crown, court, army, Temple, priesthood) became a series of abstractions, mediated by the Rabbis and funded by the community leadership, both of whom partnered with the temporal authorities to ensure the well-being of the Jewish communities. This meant that Sefarad was at once a place where Jews controlled the affairs of their communities and in which Jewish voices spoke with the authority of the Rabbinate (sublimated from that of Moses), and one where they constantly mediated with the temporal powers (caliphs, kings) who ultimately controlled their destinies. This cosmovision is significantly different from the Christological world order that characterized Christian sources and provides a very different lens through which to read Iberian literature and culture.

Israeli Chief Rabbis Itzhak Yosef and David Lau (source: Jewish Telegraphic Agency)

Works Cited

- Biale, David. 1986. Power & Powerlessness in Jewish History. New York: Schocken Books.

- Cascardi, Anthony. 2005. “Beyond Castro and Maravall: Interpelletion, Mimesis, and the Hegemony of Spanish Culture.” In Ideologies of Hispanism, edited by Mabel Moraña, 138–59. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

- Catlos, Brian A. 2017. “Why the Mediterranean?” In Can We Talk Mediterranean?: Conversations on an Emerging Field in Medieval and Early Modern Studies, edited by Brian A. Catlos and Sharon Kinoshita, 1–18. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dagenais, John, and Margaret R. Greer. 2000. “Deconlonizing the Middle Ages: Introduction.” Journal of Medieval & Early Modern Studies 30 (3): 431–48.

- Dagenais, John. 2004. “Medieval Spanish Literature in the Twenty-First Century.” In The Cambridge History of Spanish Literature, edited by David T. Gies, 39–57. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. 1989. The Souls of Black Folk. New York: Bantam Books.

- Fuchs, Barbara. 2003. “Imperium Studies.” In Postcolonial Moves: Medieval through Modern, edited by Patricia Clare Ingham and Michelle R. Warren, 71–90. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Greer, Margaret. 2006. “Hispanism and Its Disciplina.” Hispanic Issues Online.

- Múñoz-Basols, Javier, Laura Lonsdale, and Manuel Delgado. 2017. “Preface.” In The Routledge Companion to Iberian Studies, edited by Javier Múñoz-Basols, Laura Lonsdale, and Manuel Delgado, xxii–xxiv. London: Routledge.

- Resina, Joan Ramon. 2013. “Preface.” In Iberian Modalities: A Relational Approach to the Study of Culture in the Iberian Peninsula, edited by Joan Ramon Resina, vii–x. Oxford University Press.

-

Wacks, David A. 2008. “Is Spain’s Hebrew Literature ‘Spanish?’” In Spain’s Multicultural Legacies: Studies in Honor of Samuel G. Armistead, edited by Adrienne Martin and Cristina Martínez-Carazo, 315–31. Newark, DE: Juan de la Cuesta Hispanic Monographs. http://hdl.handle.net/1794/8782.

![Hardly photographic [Renoir, Chestnut Trees in Bloom (1881) Source: wikimedia commons]](https://davidwacks.uoregon.edu/files/2016/07/renoir-2hgul6l-300x235.jpg)

![True, but not Real [Lancelot and Guinevere, north-eastern France or Flanders (St Omer or Tournai), 1316, Additional 10293, f. 199. source: British Library, Medieval Manuscripts blog]](https://davidwacks.uoregon.edu/files/2016/07/prose-lancelot-28mujtc-233x300.jpg)

![David, who's your tailor? [Photo: David loads provisions in the Maciejowski Bible, New York, Morgan Library Ms M. 638, f. 27 Source: wikimedia commons]](https://davidwacks.uoregon.edu/files/2016/07/david-29k8dnw-300x190.jpg)