[You can also read the full-length article version, “Popular Andalusi literature and Castilian fiction: Ziyad ibn ‘Amir al-Kinani, 101 Nights, and Caballero Zifar” Revista de Poética Medieval 29 (311-335): http://hdl.handle.net/1794/19484]

In the last post I discussed the thirteenth-century Ziyad ibn ‘Amir al-Kinani as an Andalusi chivalric novel, one that has particular implications for how we understand the reception of Arthurian narrative in the Iberian Peninsula. In this post, I write about how Ziyad ibn ‘Amir al-Kinani is of particular interest for students of the Libro del Cavallero Zifar (Toledo, 1300).

There are a number of coincidences between Ziyad and Zifar. Most of them are on the level of narrative motif. Two episodes in particular are present in both texts but absent from popular Arabic literature in general: those of the supernatural wife who bears the hero a son, and of the underwater realm. These motifs are united in the Arthurian “Lady of the Lake”, and here find expression in Zifar in the episode of the Caballero Atrevido (González, Zifar 241–251). In Ziyad, they appear in the episodes of Ziyad’s marriage to the Princess Alchahia, mistress of the submerged castle of al-Laualib (Fernández y González 22–26), and in the following episode of his marriage to a “dama genio”, or enchanted lady (Fernández y González 30–31).

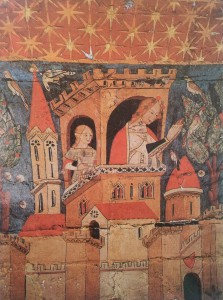

First Ziyad arrives at the castle, which each night submerges into the lake:

—When the sun rises above the horizon, the castle begins to raise from the depths of the waters, until it reaches the level of the surface of the earth. Then horses cross a vast bridge to go out and graze, and the cows and flocks of sheep to pasture. As evening falls, when the sun leans toward the west, the flocks return, and the cows and horses, and they all sink again into the water, that is, enter into Al-laualib keep, submitting themselves to its movements. (Fernández y González 19).

There Ziyad is greeted by its mistress, who is dressed as a knight. She challenges him to combat, in the course of which Ziyad notices with some surprise that his opponent is female. Finally, he defeats her and proposes marriage. She accepts and he becomes her King and lord of the submerged castle. In the following episode, Ziyad encounters an enchanted lady who bears him a son and then releases Ziyad after the boy is two years of age. One day Ziyad goes out hunting a beautiful gazelle, and becomes lost in the woods. What follows is a perfectly conventional encounter of the hero with an enchanted fairy so common in Western folkloric tradition (Thompson 1:382–384, 3:40–42, ) and abundant in French Arthurian texts (Guerreau-Jalabert 30, 62; Ruck 167, 173):

When the star [i.e., the gazelle] was hidden, I saw that it was climbing a high hill, where a road led that looked more like an ant path or the side of a beehive, she continued her flight and I followed close behind, until I came to a grotto where she hid. I dismounted and entered the grotto to give chase, and the darkness surrounded me; but in its midst I spied a damsel, radiant as the midday sun in a cloudless sky (Fernández y González 29).

The woman, Jatifa-al-horr, describes herself as “a good Jinn who believes in the Qur’an” (Fernández y González 30) (Believing jinn who marry humans are also mentioned in the 1001 Nights) (El-Shamy 69). In this way the compiler brings the Arthurian supernatural wife motif, one also present in Zifar, into line with the values of the Islamic textual community, by giving the supernatural a Quranic point of reference. She then reveals that she appeared to Ziyad in the form of a gazelle and enchanted him so that he would follow her to her hidden castle.

In these two episodes the “lady of the lake” motif is broken out into two separate episodes, each containing elements of the well-known Arthurian motif found also in Zifar. There is a good amount of speculation among critics as to the sources of these motifs, ranging from “Oriental” to “Celtic” to “Hispanic” (González, Reino lejano 103 n 25; Deyermond). It certainly is curious that the same two motifs, the only fantastic motifs in all of Zifar, whose source is contested by critics and still an open question, should appear in an Arabic manuscript from the same region written some 70 years prior to the composition of Zifar.

Depending on how we read this evidence, it could lend credence to a number of different theories about Zifar. On the one hand, if we belive the motifs are Celtic in origin, we should suppose their transmission to Ziyad through Arthurian tradition to Ziyad and thence to Zifar. This would ironically corroborate both the argument that Zifar relied on Arabic sources, and the argument for the Arthurian-Celtic sources of the fantastic episodes in Zifar.

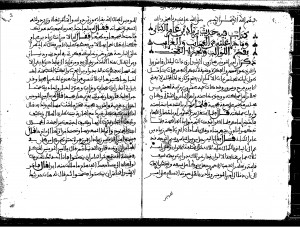

The existence of the popular storytelling tradition attested by the 101 Nights manuscript and Ziyad suggests yet another model for understanding the presence of “Arabic” source material in Zifar, in the episodes of the Caballero atrevido (‘the Fearless Knight’) and the Yslas dotadas (‘The Enchanted Islands’). (González, Zifar 240–251 and 409–429).

Suppose there were a tradition of 101 and/or 1001 Nights-style storytelling that was based on dynamic, ever-changing live performances (imagine a genre or tradition instead of a manuscript). Authors introduced new tales, adapted other tales from other traditions, and dressed them in the fictional trappings of the popular storytelling tradition of the Arab world that then produced both the 101 Nights and the 1001 Nights. We have already established that Castilian authors such as Don Juan Manuel drew on Andalusi oral narrative tradition (Wacks, “Reconquest”). What if the author of Zifar had done likewise, relying not on Andalusi manuscripts of learned Arabic texts but rather of stories told and retold within the context of the Nights tradition? The apparent Arabization of names and place names that has led critics to suppose an Arabic origin for Zifar may well be instead a reflection of a shared storytelling culture by which Castilian authors adapt material learned from storytellers in their written works, conserving and at times Hispanizing (or straight out corrupting) personal and place names, simply because that was how the Castilian author heard them.

Arabic texts of the time also reflect a shared culture of storytelling. As we have seen, place names of faraway, exotic locations such as China vacillate between Romanized and Arabized versions (Ott 258). Like the author of Zifar, the compiler of 101 Nights was drawing on a live, multilingual storytelling performance tradition in which performers told tales alternately in Andalusi Arabic or in Castilian, and likely at times some combination of both. This suggests a world of code-switching storytellers who moved effortlessly from Arabic to Castilian and back again. Only when viewed through the lens of the literary manuscript does this culture appear as two separate cultures, who communicate with difficulty through translation and adaptation. Just as with Iberian Hebrew poets who were perfectly versed in Romance popular culture, but who were compelled by literary convention to write almost exclusively in Hebrew, our authors and compilers of 101 Nights, Ziyad, and Zifar recorded in monolingual form a tradition that was in practice at least bilingual and probably to a certain extent interlingual as is today’s US Latino culture, where English, Spanish, and Spanglish coexist on a continuum of linguistic practice.

Conclusions

The evidence Ziyad presents is compelling on two counts. On the one hand, Ziyad’s analogues of Arthurian motifs episodes found in Zifar complicate the question of Zifar’s putative Arabic sources. We must choose one of the following: did the Arthurian material pass from the French to Ziyad and thence to Zifar? This would be a delicious but perfectly Iberian irony for the Zifar to have received Arthurian material from an Andalusi text. Or alternatively, did both Ziyad and Zifar take the material directly from the French? Or, a third and in my opinion more likely alternative: that the Arthurian material entered the Iberian oral narrative practice, where both Ziyad and Zifar collected it. This thesis finds strong support in scholars’ assessment of the Andalusi storytelling practice reflected in the 101 Nights manuscript.

Ziyad and 101 Nights both attest to a corpus of Andalusi written popular literature giving voice to a specifically Iberian (or at least Maghrebi) experience vis-a-vis the Muslim East. This corpus is largely latent and we await quality critical editions and translations into other languages of Ziyad, the other 11 texts in Escorial Árabe MS 1876, the 101 Nights, and other texts as they come to light. Our findings are necessarily tentative, based as they are on translations, until these editions come to light. What we can state, however, is the following: Ziyad provides us with new, earlier examples of the penetration of Arthurian themes and motifs in the Iberian Peninsula that predate both the Castilian translations of the Arthurian romances as well as their adaptation in Caballero Zifar. These versions circulated in a multi-lingual, multi-confessional Iberian narrative practice that included both oral and written performances. All of the above changes our understanding of Caballero Zifar and potentially many other early works of Castilian prose fiction as part of a literary polysystem with an oral component that is underrepresented in the sources yet important for understanding the development of literary narrative in Iberia.

Works Cited

- El-Shamy, Hasan M. A Motif Index of The Thousand and One Nights. Bloomington, Ind: Indiana University Press, 2006. Print.

- Fernández y González, Francisco, trans. Zeyyad ben Amir el de Quinena. Madrid: Museo Español de Antigüedades, 1882. Print.

- González, Cristina. “El cavallero Zifar” y el reino lejano. Madrid, España: Editorial Gredos, 1984. Print.

- —, ed. Libro del Caballero Zifar. Madrid: Cátedra, 1984. Print.

- Guerreau-Jalabert, Anita. Index des motifs narratifs dans les romans arthuriens français en vers (XIIe-XIIIe siècles). Geneva: Droz, 1992. Print.

- Ott, Claudia. “Nachwort.” 101 Nacht. Zurich: Manesse Verlag, 2012. 241–263. Print.

- Ruck, E. H. An Index of Themes and Motifs in 12th-Century French Arthurian Poetry. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1991. Print.

- Thompson, Stith. Motif-Index of Folk-Literature. Rev. and enl. ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1932. Print.

- Wacks, David A. “Reconquest Colonialism and Andalusi Narrative Practice in Don Juan Manuel’s Conde Lucanor.” diacritics 36.3-4 (2006): 87–103. Print.

This post is based on a paper I gave at the 50th International Congress on Medieval Studies at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo. Thanks very much to Anita Savo for organizing the panel “Routes of Translation in the Medieval Mediterranean.”