[This post includes material later revised and expanded in Double Diaspora in Sephardic Literature: Jewish Cultural Production before and after 1492 (Indiana University Press, 2015)]

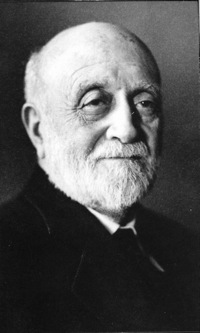

Todros Ben Yehudah Halevi Abulafia (1247- ca. 1295) lived and wrote in Toledo in the second half of the thirteenth century. He was active at the court of King Alfonso X “the Learned.” Among Hebrew poets in Christian Spain, Abulafia was unique in several ways: he was the only Jewish poet to enjoy the direct patronage of a Christian king, and dedicated several poems to Alfonso. He was, even among Jews who held positions at court, considered more assimilated, more given over to life among the gentiles, and a famous womanizer, and a partier. He documented some of these exploits in his poems, some of which are excerpted in Peter Cole’s Dream of the Poem (2007). There is also a 2009 Hebrew selection edited by Israel Levin.

Abulafia is a diasporic poet who is a shadowy outsider from any angle. After 1492, he became a poet without a state. In Spain he is virtually unknown, despite having written hundreds of poems at the court of that country’s most intellectually important medieval ruler. He is not mentioned in any of the studies of the Christian troubadours who wrote and performed at Alfonso’s court. He scarcely appears in historical studies of Alfonso’s reign (see Wacks 2010, 194 n 38), even in those that deal specifically with the boom in arts and letters for which Alfonso X is famous (and the reason why he is known as ‘the Learned’).

Jewish scholars have viewed him at times with admiring curiosity, at times with disdain. He is still a bit of an enigma. Peter Cole aptly sums up the diverse opinions scholars have formed of Abulafia: one called him “one of the greatest poets of whom the Jews can boast,” while others dismiss him as a “mediocre epigone” (2007: 493).

Abulafia lived at a time when the upper classes of the Jewish community of Toledo were waging a sort of culture war. One side leaned toward assimilation and materialism, another toward traditionalism and piety. This division was personified in Todros ben Yehudah Halevi and his relative, the ‘other Todros’: Todros ben Yosef Halevi Abulafia, a prominent Talmud scholar and Chief Rabbi of Toledo.

The Brotherhood of the Traveling Manuscript

The story behind his collected poems (diwan) is something that Cervantes (that master of the “found manuscript” conceit) might have cooked up. Up until the late 19th century, scholars of Spanish Hebrew poetry were familiar with Abulafia’s name and had found a few of his poems, but he was a minor player, a footnote. As it turns out, he had written and compiled a huge corpus of his own work – some twelve hundred poems. Abulafia was one of the first poets in Hebrew or the Romance languages to compile his own diwan (collected poems), although this was standard practice among medieval Arab poets.

In the 17th century, an Egyptian Jewish scribe made a copy of Abulafia’s diwan. It passed from one antiquities dealer to another and eventually found its way into the hands of Saul Abdallah Yosef (1849-1906), an Baghdadi Jewish businessman and accomplished amateur scholar. Yosef made a copy of the manuscript and brought it back to to his home in Hong Kong. The Romanian-British Jewish scholar Moses Gaster published a facsimile edition of Yosef’s manuscript, which the Israeli scholar David Yellin used as the basis for a 1932 critical edition. Yosef’s discovery of the manuscript fairly doubled the corpus of Hebrew poetry from the time of Alfonso X, and radically changed our understanding of the poetry of 13th-century Spanish Jewry.

Tell me where you come from, and I’ll tell you what you think about Abulafia

Most interesting about Abulafia is his reception by contemporary scholars. From where I’m standing, as an American Jew living in the 21st century, it doesn’t strike me as at all strange that Abulafia’s poetry sounded like the poetry of his Christian peers. I imagine that even if US Jewish authors typically wrote in Hebrew, their writing would be full of material from American movies, popular music, novels, and poetry. This is precisely what happens with Abulafia’s poetry. He talks about love, at least part of the time, like a Provencal troubadour. Without abandoning the Hebrew poetic tradition of Muslim Spain, he fully participates in the literary tastes of his time, tastes shaped by the Romance-language literatures practiced in Castile.

Scholars of Abulafia, Judaism aside, bring to the table very different cultural formations. Most are European Jews who relocated to Palestine before World War II. Their take on Abulafia’s relationship to the cultures of homeland (Jewish) and hostland (Spain) are conditioned by their own relationships to their various homelands and hostlands. Saul Abdallah Yosef was an Arab Jew, who grew up in Baghdad in a very large and vibrant Jewish community that (it being before 1948) was far less conflicted about their Arab-ness than Mizrahi Jews would come to be in post-1948 Israel. His own (relatively) untroubled biculturality allowed him to appreciate Abulafia’s ease with Christian culture. Likewise, Moses Gaster (he was the one who called Abulafia “one of the greatest poets”) was a Romanian Jew who became a British citizen, and an expert on Romanian folklore in addition to Hebrew literature. For him it would have been natural to celebrate Abulafia’s biculturality.

Those critics who were born in or migrated to Palestine/Israel had a different orientation. The Zionist experience reintroduced Jews to sovereignty as once -symbolic homeland suddenly became a modern state. This changed dynamics between diasporic (hostland) and Jewish (now also Israeli) culture, and this changed how critics talked about Abulafia’s poetry.

Heinrich (Henrik, then Hayyim) Brody was Chief Rabbi of Prague and a leader of the Zionist movement in Austro-Hungary before emigrating to Palestine. Together with David Yellin, a native Jerusalemite and fervent defender of Hebrew education (there is a teacher’s college named after him in Jerusalem), Brody dismissed Abulafia’s troubadour-inspired innovations as “mediocre” (cited in Cole 2007: 243) The Romanian-born Israeli scholar Ezra Fleischer, best known for his studies of liturgical poetry, likewise held Abulafia’s assimilating ways in low regard.

Hayim (Jefim) Schirmann, who succeeded David Yellin as Chair of Medieval Hebrew Poetry at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University and edited the landmark anthology Hebrew Poetry in Spain and Provence (1954-56), held a very different opinion of Abulafia’s cosmopolitanism. Schirmann, though born in Kiev, attended gymnasium and university in Berlin, emigrating to Palestine in 1934. He was an avid violinist whose interest in music guided his academic interests. He was so committed to secular culture that he lobbied to repeal the ban on the performance of Wagner’s compositions in Israel. Schirmann was not going to let politics get in the way of a good opera. Among Israeli critics he most clearly vindicates Abulafia’s ‘troubadourism’ as a natural characteristic in a diasporic Jewish author.

The more Zionist critics of Abulafia tend to regard his innovations as a sort of ‘betrayal’ of Andalusi poetics (i.e., the poetic style typical of the Jews who lived in Muslim Spain). By the first half of the twentieth century, Andalusi Hebrew poets such as Samuel Hanagid and Moshe Ibn Ezra were firmly established as the grandfathers of modern Hebrew literature. It is somewhat ironic that a generation of European-born critics considered the undeniably Arabic style of the Andalusi Hebrew poets to be the ‘poetic homeland’ of modern Hebrew, while the European-influenced poetry of Abulafia was for them ‘foreign’ and somehow, disloyal to Jewish values.

- Barzilay, Isaac. “Hayyim (Jefim) Schirmann (1904-1981).” Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research 49 (1982): xxv-xxxi.

- Cole, Peter. The Dream of the Poem: Hebrew Poetry from Muslim and Christian Spain, 950-1492. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Levin, Israel, ed. Shirim. Todros Ben Yehudah Halevi Abulafia. Jersualem: Tel Aviv University 2009.

- Schirmann, Jefim. Hebrew Poetry in Spain and Provence [Hebrew]. Jerusalem; Tev Aviv: Mossad Bialik; Dvir, 1954-1956.

- Wacks, David. “Toward a History of Hispano-Hebrew Literature of Christian Iberia in the Romance Context.” eHumanista 14 (2010): 178-209.

This post was written with support from the Oregon Humanities Center