[For the revised and expanded version of this post, see “Translation in Diaspora: Sephardic Spanish-Hebrew Translations in the Sixteenth Century.” A Comparative History of Literatures in the Iberian Peninsula. Ed. César Domínguez & María José Vega. Vol. 2. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2017. 351-63. https://hcommons.org/deposits/item/hc:10227/]

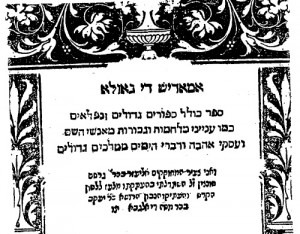

In two previous posts I wrote about the cultural context and actual translation of the Spanish chivalric novel Amadís de Gaula (Zaragoza, 1507) into Hebrew made by Sephardic physician and translator Jacob Algaba (Constantinople, 1550). Here I would like to expand my discussion of translation from Spanish to Hebrew made in the sixteenth century to include another book well-known to students of Spanish literature: Joseph Hakohen’s 1557 translation of Francisco López de Gómara’s Historia General de las Indias (Zaragoza, 1552).

When we read these translations as examples of Sephardic diasporic cultural production, the Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula, we begin to see a different picture. Their translators placed these works in the service of a Jewish literary culture, one whose values were often at odds with those of the original authors and readers of the Spanish originals. At the same time, the Sepharadim were deeply identified with Iberian vernacular culture and history, and these translations were a form of cultural capital upon which they traded in the broader Jewish context of Western Christendom and the Ottoman Empire.

Diaspora

Diaspora is a Greek word that describes the broad scattering of a people as if they were seeds scattered across several furrows in a field. In its original usage it described the colonization of people dispersing from metropolis to colonies in order to reproduce Imperial authority in conquered lands. In the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible it came to mean the dispersion of the Jews from Zion throughout the Mediterranean and Middle East. Since then it has come to be applied to range of historical scatterings: African, Indian, Chinese, Armenian, and others. In other posts I’ve written on how current ideas about non-Jewish diasporas can be helpful for thinking about Jewish diaspora, and in particular the Sephardic ‘double diaspora’ from Zion and from Sefarad. [see previous post on double diaspora]

Translation

Diasporic populations are by nature multilingual. They typically use one or more diasporic languages brought from the homeland in addition to one or more languages of the hostland. It follows that translation across these languages would be an important part of their cultural life.

Diaspora is often presented as an alternative to the idea of national languages and literatures (Tölölyan, “Transnational” 8). Lawrence Venuti, an expert on translation in literature, writes that translation can be part of a nationalist cultural agenda:

Foreign texts are chosen because they fall into particular genres and address particular themes while excluding other genres and themes that are seen as unimportant for the formation of a national identity; translation strategies draw on particular dialects, registers, and styles while excluding others that are also in use; and translators target particular audiences with their work, excluding other constituencies. (“Local 189-90)

Although diasporic and national cultures are different, in both cases translation can serve similar purposes. Sephardic Spanish-to-Hebrew translations bring texts over from a language of national and imperial culture into one of a diasporic language of learning. They reauthorize the works for consumption by the broader, non-Sephardic Jewish community, so their motives for translation were not to make the works in question intelligible to themselves, but rather to represent some version of Spanish or Sephardic culture to the broader Jewish world.

In these translations, we see a conflicting desires at work: on the one hand our translators sought to bring Spanish literature to a broader Jewish audience. In this they were banking on the prestige of Spain as a world power, as a source of great literature, and to a certain extent they identified with Spain’s prestige. But at the same time, their relationship with Spain was conflicted: it was at once their ancestral homeland and the country whose kings had brutally rejected and ejected them. Hakohen’s translation of López de Gómara’s account of the conquest of the Americas demonstrates this conflict in some interesting ways, as we are about to find out.

Hakohen’s Historia de las Indias

Francisco López de Gómara, secretary and chaplain to Hernán Cortés in Seville, published his second-hand account of the conquest of the Indies in Zaragoza in 1552. It was later decried as inaccurate and overly rosy in its portrayal of the Spanish colonial enterprise, and particularly in its lionization of Cortés himself. Such objections notwithstanding, it provided readers with a detailed —if inaccurate— account of the geographic, political, and social realities of New Spain, by any measure an exciting and relevant topic of discussion in Spain and elsewhere.

The first half of the sixteenth century saw a surge in Jewish historiography. Jewish writers began to write chronicles and histories that recorded events of importance to Jewish communities, the succession of gentile kings, wars, calumnies, expulsions, and so forth. While some historians of Jewish culture have explained this apparently sudden interest in historiography as a reaction to the trauma of the expulsions from Spain and from various Italian city states, it was more likely simply a sign of the times (Bonfil, “Golden”). In the age of print, exploration, and complex international trade networks, global politics and history was now part of the dossier of a good Jewish courtier or businessman.

Joseph Hakohen was an Italian Jew of Sephardic background and author of a number of secular histories in Hebrew (León Tello, “Introducción” 25-35). In the introduction to his Chronicles of the Kings of France and the Kings of the House of the Ottoman Turk, he writes that it is good to learn of the deeds of great kings against the Jews so that, as he writes in his introduction to his “that the remembrance thereof not pass away from among the Jews; and the memory of our wrongs shall not come to an end” (Hakohen, Chronicles 1: xx). But the Hebrew histories of the sixteenth century were more than updated lamentations of Jewish suffering; they were guidebooks to a globalizing world that negotiated between imperial contexts. This increased interest in international affairs should come as no surprise given Jewish involvement in diplomacy and international trade.

We must keep in mind that Hakohen’s Historia de las Indias appeared in 1557, five years after Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas’ Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias (1552) discredited López de Gómara’s history as a blatant fabrication and puff piece meant to validate Spanish conquest in the New World. Hakohen’s treatment of Gómara’s work is likewise highly critical. Why translate a work only to criticize and undermine it all the while? Moshe Lazar, the modern editor of Hakohen’s translation, notes that Hakohen embeds a critique of the Spanish colonial project similar to that voiced by Las Casas. Hakohen editorializes liberally in his translation of the events narrated by López de Gómara, freely glossing and emending López de Gómara’s text to bring it in line with his own values and those of his audience.

In one striking example, López de Gómara recounts the triumphant return of Christopher Columbus to the court of the Catholic Monarchs, where he is given a hero’s welcome. Gómara describes the coat of arms presented to the Genoese navigator, which he inscribes with a couplet celebrating his own achievements:

Puso Christoual Colon al rededor del escudo de armas, que le concedieron, esta letra:

Por Castilla, y por Leon.

Nueuo mundo hallo Colon. (López de Gómara, Historia 22)Christopher Columbus put this inscription around the coat of arms that they gave him:

For Castile, and for Leon.

Columbus found a new world.

Hakohen, somewhat more critical of Columbus’ project, glosses the couplet, first reproducing it in Spanish (with a slight variant) in Hebrew letters, followed by a poem of his own composition:

Por Castilla y por León

Medio el mundo halló ColónFor Castille and for Leon

Columbus found half of the worldAnd I, Joseph Hakohen, composed the following, saying:

For Castilla, and also for Leon

Colon found a new world

But with the passage of the sun through the sky,

they crossed into the Valley of Ayalon (Joshua 10:12-13)

There he earned eternal fame

For there he also found a colony

Thus many nations were humbled

In great reproach, contempt and dishonor,

For this man crossed there,

to become the mistletoe [i.e. a parasite] to their oak.

Elsewhere he frankly contradicts López de Gómara’s version of events, offering a counter history to the hegemonic narrative of the Spanish original. For example, López de Gómara’s chapter on syphillis is plainly titled “Que las bubas vinieron de las Indias,” or ‘syphillis came from the Indies.’ (Historia 37-38).

He explains that Spanish conquistadors contracted syphillis by having sex with indigenous women from the island of Hispaniola, then returned to Spain. Subsequently they traveled to Naples to fight the French, where they infected Italian women with the disease:

Los de aquesta ysla Española son todos bubosos. Y como los Españoles dormian con las Indias hinchieronse luego de bubas, enfermedad pegajosisima, y que atormenta con rezios dolores. Sintiendose atormentar y no mejorando, se boluieron muchos dellos a España por sanar, y otros a negocios, los quales pegaron su encubierta dolencia a muchas mugeres cortesanas, y ellas a muchos hombres, que passaron a Italia a la guerra de Napoles en fauor del rey don Fernando, el segundo, contra Franceses, y pegaron alla aquel su mal. (Historia 36-37)

The inhabitants of that island Hispaniola are all syphillitic. And as the Spanish slept with the Indian women they then became infected with syphillis, that most contagious disease that torments one with fierce pains. Feeling afflicted and not improving, many went back to Spain to recover, and others to conduct business, by which they infected many courtesan ladies who in turn infected many men who went over to Italy to the War of Naples on the side of King Fernando II, against the French, and there they spread their disease.

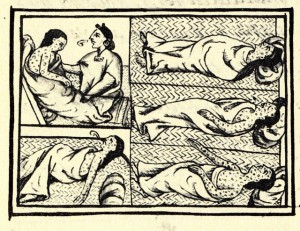

Without editorializing, Hakohen turns López de Gómara’s narrative on its head, substituting a very different epidemiology of the Columbian exchange that runs counter to López de Gómara’s official narrative. Hakohen’s chapter is titled “Syphillis is a French sickness, that the Spaniards brought from there, and they also brought the hordeolu (orzuelo, ‘stye’) illness.”[1] His version differs considerably from that of López de Gómara:

The Spaniards brought syphillis to Italy from the Indies when they went to Naples, in the year 1494. They slept with women, and French also slept with them, and the syphillis shone [first] in their foreheads and in time ate half of their flesh. . . . And the Spaniards also brought hordeolu (styes) and morbili (measles), which is called jidri in Arabic,[2] and smallpox, which the inhabitants of that land had never seen before that day; and many thousands of them died of those two illnesses. Their time of their [death] warrant had come upon them then. (Sefer ha-Indiah 30-31)

The constrast is dramatic. Hakohen reverses the trajectory of infection, returning the origin of the pestilence to Europe and backing up his version by adding details and citing medical authorities absent in the Spanish original. He is clearly at odds with López de Gómara, particularly as regards the morality of Spain’s colonial project.

This hostility to Spanish conquest is hardly unique to Hakohen. We have noted the well-known case of Las Casas. There were also a number of of Hakohen’s countrymen in Italy who took up their pens against Spain. The most prominent among these was Girolamo Benzoni, a Milanese whose bitter failures in his brief time in the new world engendered in him a vibrant hate of all things Spanish. Benzoni gives voice to this hatred unstintingly in his Historia del nuovo mundo, published in Venice in 1565, eight years after Hakohen finishes his translation of López de Gómara.

Unlike Benzoni, Hakohen’s relationship to the Spanish colonial enterprise is more complicated: he is describing a culture of which he is a part but from which he has been excluded. When Sephardic authors such as Hakohen write about Spain, or adapt works by Spanish authors, they are in a sense turning and re-turning toward Spain, but this orientation toward the diasporic homeland is the product of human history and not part of any divine plan. However, the strong attachment to Sepharad/Spain expressed by Sephardic writers intertwines and alternates with the desire (if not the actual project) of returning to Zion.

This contains material from a talk I gave at the Dept. of Spanish and Portuguese of the University of Colorado at Boulder on 1 November 2012. My thanks to the Department and to the Center for Humanities and Arts for their support.

I appreciate your feedback and comments. Feel free to leave a comment below or email me.

Works cited

- Bonfil, Robert. “How Golden was the Age of the Renaissance in Jewish Historiography?” History and Theory 27.4 (1988): 78–102. Print.

- Hakohen, Joseph. Sefer Divre Ha-yamim : Le-malkhe Tsarefat U-malkhe Bet Oṭoman ha-Tugar. Ed. David Arie Gros. Yerushalayim: Mosad Byaliḳ, 1955. Print.

- —. Sefer ha-Indiʼah Ha-hadashah. Ed. Moshe Lazar. Lancaster, CA: Labyrinthos, 2002.

- —. Sefer ʼEmeq Ha-bakha = The Vale of Tears : with the Chronicle of the Anonymous Corrector. 2nd ed. Ed. Karin Almbladh. Uppsala: Uppsala University, 1981. Print.

- León Tello, Pilar. “Introducción.” El Valle Del Llanto (’Emeq ha-Bakha). Joseph Hakohen. Trans. Pilar Léon Tello. Barcelona: Riodpiedras, 1989. 9–35.

- López de Gómara, Francisco. La historia general De las Indias y Nueuo Mundo con mas la conquista del Peru y de Mexico. Antwerp: Juan Steeliso, 1554.

- Tölölyan, Khachig. “Rethinking Diaspora(s): Stateless Power in the Transnational Moment.” Diaspora 5.1 (1996): 3–36.

- Tölölyan, Khachig. “The Contemporary Discourse of Diaspora Studies.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 27.3 (2007): n. pag. Web. 20 July 2011.

[1] Hakohen uses the Hebrew term holei ha-tavelei for the Spanish bubas.

[2] Jidri is Andalusi Arabic for smallpox. The Classical Arabic form is judari. It is interesting that Hakohen is familiar with the colloquial rather than learned form, which suggests that he learned it in discussion with an Arabic speaker, rather than from consulting an Arabic book or a Latin or Romance translation of an Arabic book.