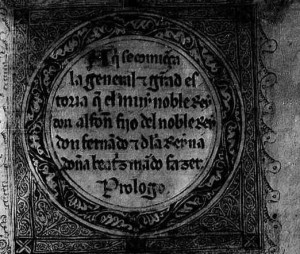

Alfonso X of Castile-Leon (r.1252-1284) compiled a massive universal history titled the General estoria, an ambitious project meant to encompass all of known history, from creation to the current era. The General estoria included a good deal of biblical material, vernacular versions of selected books of the Old and New Testaments. Vernacular versions of the Bible were a bit of risky proposition in an age when vernacular translations of the Latin Vulgate were technically not allowed. But Alfonso X was an intellectual, perhaps a bit of a free thinker, and in some cases his push for greater openness in knowledge production rubbed up against orthodoxy.

In come cases the biblical material in the General estoria seems to be engaging in exegesis (interpretation of biblical texts) and not simply directly rendering the text of the Latin Vulgate bible into thirteenth-century Castilian. There are asides, digressions, glosses, and variants, all of which suggest that the compilers of the text drew on a variety of sources that included, in addition to the Latin Vulgate Bible and the works of Christian commentators, the Hebrew Old Testament (Tanakh) and the works of Jewish commentators. In this entry, I discuss my analysis of the Cantar de Cantares (Song of Songs) included in the General estoria.

To what extent is the Alfonsine Castilian Cantar de Cantares a product of intellectual collaboration between Jewish and Christian scholars? That is, as Prof. Guadalupe González has remarked, given that Jews did not write history books for Jews in the thirteenth century, did some of them perhaps have a hand in writing history books for Christians? This is a difficult question to answer. Typically when a Christian author incorporates Jewish sources, they do not cite them, unless they are writing a polemic text meant to refute the Jewish source in question. But when the Jewish source is being used to enrich or round out the knowledge base of the Christian author, one usually has to do a bit of detective work in order to identify sources.

For this reason I would like to spend a couple of minutes talking about methodology. How do you read a Castilian Biblical translation with an eye toward parsing out the “Jewish” —and I put the word “Jewish” here in scare quotes because of the philosophical question of what is a Jewish author or a Jewish text when we are not talking about a text used by a practicing Jew in the practice of Judaism or in the context of a Jewish audience. By way of comparison one might think of the fourteenth-century didactic poem Proverbios Morales, written by Rabbi Shem Tov ben Isaac Ardutiel de Carrión in Castilian for King Pedro III ‘The Cruel.’ [see related blog post here] The poem contains references to a number of Jewish sources but does not cite them, nor is it overtly Jewish, that is, it does not explicitly address Jewish scriptural, exegetic, or moral questions. Conversely, the Cantar de Cantares in the General estoria is explicity a Christian text, in the sense that it was written for a Christian patron in the framework of Christian religion. However, some aspects of the translation (and we must use this term in the more capacious medieval sense that we might better translate in the modern context as ‘version’ or ‘interpretation’) point to Jewish sources.

Corpus comparison of General estoria, Vulgate, and Tanakh at the Biblia Medieval website

(http://corpus.bibliamedieval.es/)

But how can we tell? There is a good deal of interference to deal with. The Cantar de Cantares mostly follows the Vulgate, which in turn is a (rather faulty) translation from the Hebrew and as such has linguistic and interpretive characteristics that are particular to the Hebrew Tanakh. Likewise, early Christian commentators of the Song of Songs such as Origen were influential on both Christian and Jewish exegetical tradition. This and other factors muddy the waters a bit when we are trying to positively identify what we might call “Jewish” or “Christian” influences on the Alfonsine Cantar de Cantares.

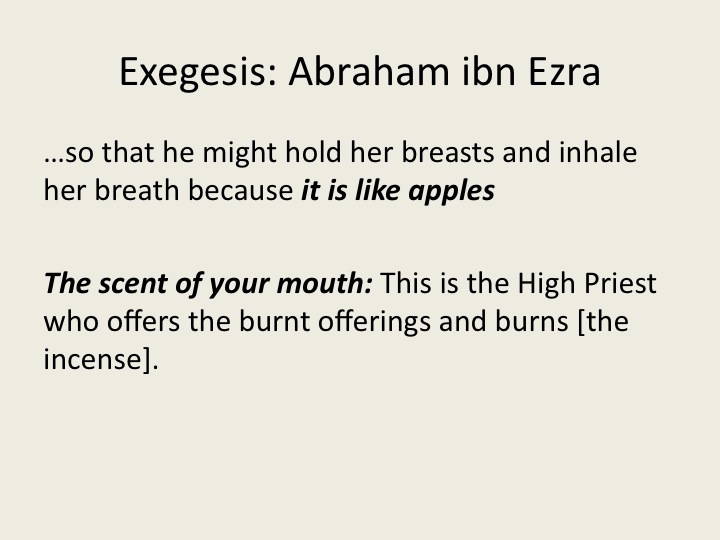

I began by reading different versions side by side: the Cantar de Cantares next to the Vulgate next to the Tanakh, and noting where the Alfsonsine version differed from the Vulgate and from the Tanakh, giving especial attention to where it differed from both. In the cases where the text seemed to deviate from the Vulgate I tried to find explanations in medieval Jewish exegetes, especially the commentaries of Rashi and of Abraham ibn Ezra, both of which pay attention to the literal sense of the Song of Songs. This is important because the Alfonsine translation is quite literal for the most part and makes no reference whatsoever to the traditional allegorical interpretations of the Song that dominate all discussion of the text in sacred contexts.

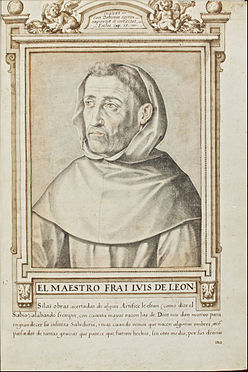

Luis de León, in Libro de descripción de verdaderos retratos, ilustres y memorables varones (The book of description of real portraits, illustrious and memorable men) (Francisco Pachecho, 1599) Source: wikipedia

Most medieval commentators were wary of discussing the literal meaning of the Song. In fact, one could get into quite a bit of trouble by considering the literal meaning apart from its traditional interpretations as the story of the love between God and the Church, God and Israel, or (from the twelfth century forward) God and the individual believer. But in the end, as Luis de León boldly demonstrates in the sixteenth century, with disastrous results, the Song of Songs is a love song, a racy, sexy, downright filthy love song, depending on your reading, and any rigorous allegorical interpretation of it needs to begin at that level with the sweaty encounter between the Shulamite and her beloved. In the thirteenth century such commentaries would have been quite rare.

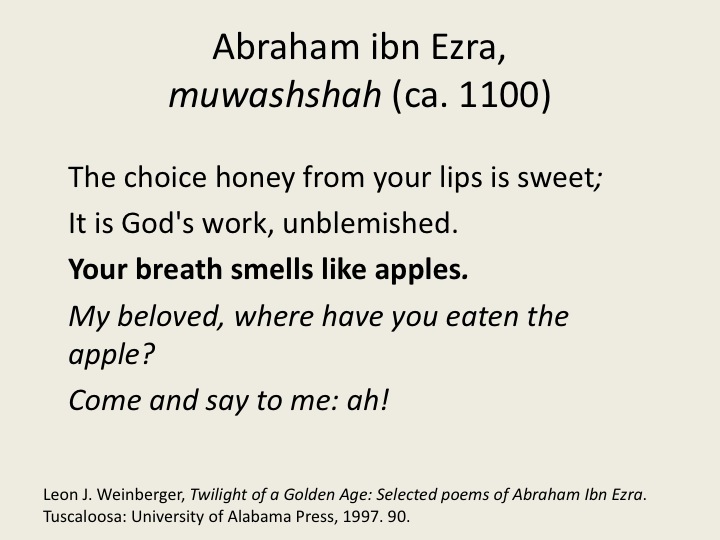

There are many many commentaries on the Song of Songs, but among the most influential for both Christian and Jewish commentators and especially translators would have been the Sephardi Abraham ibn Ezra (1089-1167), and the French Rabbi Rashi of Troyes (1040-1105). Ibn Ezra was an Andalusi polymath who fled persecution at the hands of the radical Almohad dynasty in the 1140s. He fled North across the Pyrenees, where he was able to parlay his Andalusi education into a brilliant career as an itinerant intellectual. In addition to his commentary on the Song of Songs he wrote a series of books on scientific and religious topics and is still to this day an important reference for Jewish rabbinics. Ibn Ezra insisted on a grammatical and literal reading as a sound basis for allegorical and midrashic interpretation. Rashi likewise spends a good deal of time on the poem’s philology, and is known for his careful attention to the vernacular French of his time. It should therefore not surprise that scholars working to translate the Song of Songs into their own vernacular should incorporate Rashi’s explanations in their approach to the text.

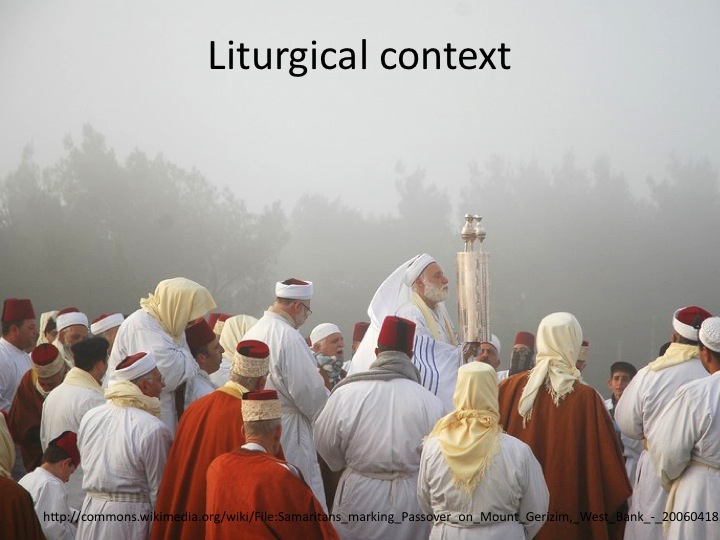

What does it mean, then, for a translation to be between Christian and Jewish traditions of biblical interpretation? Let’s consider for a moment what kind of text this Song of Songs itself purports to be. The General estoria is not meant to be a religious document. It was not written for use in the Church and is not per se a ‘sacred’ text. It comes from the scriptorium of a Christian king, yet one who is known to be intellectually open minded, and who ordered, in addition to his corpus of scientific translations, Castilian translations of the Qur’an, the Hebrew scriptures, and even the Zohar, which was probably compiled during his reign. He even established school of Arabic studies in Seville to train future translators, diplomats, and polemicists. But the General estoria is just that, a history book, one that means to account for human history from Biblical prehistory to modernity. As such it approach to the Song of Songs skews to the historical and away from the allegorical, an approach that was highly suspect and potentially heretical —if it had been a religious text, which is was not. The compilers apply this approach in their theory of the order of composition of the Solomonic books, Song of Songs, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes:

Agora, comoquier que los santos padres ordenaron en la Biblia en otro logar los cuatro libros que Salomón fizo, nós por la razón que los compuso Salomón tenemos por buen ordenamiento de los poner luego empós la su istoria d’él, porque vengan todos los sus fechos unos empós otros por orden, assí como él los fizo, nós catando los tiempos e las edades según que Salomón dixo las palabras d ‘estos libros, porque los dichos de Cantica canticorum acuerdan con la edad de la mancebía, cuando los omnes se trabajan de cantares e de cosas de solares, ordenamos en esta historia que fuesse primero Cantica canticorum. E otrossí porque los omnes desque sallen de aquella edat e entran a la otra de mayor seso e acuerda con esto el libro de los Proverbios pusimos éste empós Cantica canticorum. E otrossí porque aviene adelante edat de mayor seso que todas las otras que son passadas, e fabló Salomón en el libro de Sapiencia del saber de las cosas, nós ordenamos por ende este libro en el tercero logar empós estos otros dos, assí como tenemos que conviene. Aun otrossí, los omnes pues vienen a la vejez e veen que las cosas que an passadas que non son nada, desprecian el mundo e las sus cosas. E porque fabló Salomón d’este despreciamiento del mundo en el libro Eclesiastés pusiémoslo postremero d’estos cuatro libros.

Now, as the Holy Fathers elsewhere put in order the four books that Solomon wrote, we believe that the proper order of their composition is according to his own personal history, as they appear to come one after the other in the order he wrote them, we take into account the times and ages in which Solomon write the words of these books, for the sayings of the Song of Songs match the age of youth, when men write songs and pastoral compositions, we put the Song of Songs first in this history. And because when men leave that age and enter into the next one of better judgment, the book of Proverbs matches that one, and so we put it after the Song of Songs. And because next comes an age of greater judgment than the ones that come before it, and Solomon spoke in the book of Wisdom of knowledge, we therefore put that book in the third position after these other two, as we see fit. What’s more, men then come to old age and see that the things that have happened are worth nothing, and they come to despise worldly things. And because Solomon spoke of this in Ecclesiastes we put it in the final position of these four books.

This reordering flies in the face of Christian exegesis of the times, that explains the canonical ordering of the Solomonic books as a progression of ever more sophisticated grasp of revelation, culminating, not beginning, with the Song of Songs, the highest and most sacred expression of human wisdom regarding Divine revelation, a work that must pale in importance beside the more pragmatic Proverbs and the bummer Ecclesiastes. Surely only a mature man could have written such a sublime poem? For this very reason a number of commentators both Christian and Jewish recommend restricting readership of the Song to mature males, much as they would the reading of the Zohar in the medieval period.

Petrus Comestor presents the Bible Historiale to Archbishop Guillaume of Sens in the Bible Historiale Complétée (ca. 1370-1380). Source: wikipedia

So, either the compilers of the General estoria invented this psycho-social developmental approach from whole cloth or adapted it from another tradition. As it turns out, this approach to the Solomonic books is in Rashi’s commentary, in turn based on the interpretation found in Midrash Rabbah. This is an interesting turn of events, but not shocking exactly, and not confirmed. Just because Rashi said it doesn’t mean the General estoria got it from Rashi. Earlier Christian commentators borrowed from Jewish interpretations, and the compilers might have gotten it from one of them. Peter Comestor (d. 1178), who was born in the same city where Rashi lived, is known to have consulted Jewish commentators in compiling his massive Historica scholastica, a Latin universal history from which the General estoria borrows considerably. But Comestor did not include the Song of Songs in his opus, and made no such comments about its order within the Solomonic corpus, even though he was perfectly placed to have known some of Rashi’s students. But for now, let us leave open the question of how this bit of Jewish exegesis made its way into the General estoria and examine a few other examples.

Vernacularization

A couple of these examples fall into the category of vernacularization, of making the literal translation of the Castilian more intelligible, more lexically or grammatically familiar to speakers of Castilian. For example, in book 4, verse 3 the poem describes the beloved’s lips as “sicut uitta coccinea” (like a scarlet ribbon), which is close to the Tankh’s ‘scarlet thread.’ Here the General estoria reads ‘toca de xamet,’ a cloth used as a woman’s head covering that the RAE defines as a ‘rica tela de seda, que a veces se entretejía de oro’ (a rich silk fabric, that is sometimes interwoven with threads of gold). The Castilian reading evokes a well-known and specific type of cloth that signifies luxury to the Castilian speaker, but departs somewhat in its formal sense from the Vulgate’s “ribbon” or the Tanakh’s “thread” in that it is no longer a narrow strip of red emphasizing the fineness of the beloved’s lips. Here the vernacular sensibility seems to trump the literal sense of the biblical text.

Elsewhere the translators seem to be glossing the Vulgate in order to make unfamiliar words or forms intelligible to the Castilian reader. For example in book 5 verse 13, speaking again of the beloved’s lips, the poem says “labia eius lilia distillantia murram primam” (her lips are lilies that distill prime myrrh), for which the Castilian reads “Los sus labros destellantes de la primera mirra (mejor que todas las otras).” Here the Castilian version glosses the meaning of “primam” as an indicator of high quality. In book 7 verse 2 the poet describes the lover’s bellybutton as “crater tornatilis” (a turned bowl), which the Castilian renders as “vaso tornable (como fecho en torno)” adding the parenthetical gloss that explains the adjective ‘tornable,’ itself a very direct rendering of the ostensibly oscure latin ‘tornatilis.’ It is noteworthy that the compilers do not seem to resort to the Tanakh in order to resolve obscure readings of the Vulgate, as they do elsewhere in the General estoria.

“Some say it is the color of the sky” Aigue-marine. Provenance: Shigar Skardu, Pakistan. Source: Wikipedia

Finally, in a very few cases the compilers seem be adding details that are absent in the Vulgate. In book 2, verse 10 the poem exhorts the beloved to come away with him: “Levántate e apressúrate, mi amiga, mi paloma fermosa, e vein.” The term ‘formonsa mea’ (my beauty) is emended in the Castilian as ‘paloma fermosa’ (beautiful dove), a detail that is absent from both Vulgate and Tanakh. This variant does not appear in any of the commentaries I have consulted, so we can tentatively conclude that it is an artistic innovation of the compilers, perhaps another example of vernacularization if ‘mi paloma fermosa’ were a common term of endearment in thirteenth-century Castile.

In at least one example, such emendations appear to be inspired by, or at leat correspond with commentary by specific Jewish exegetes. In book 5, verse 14, the poem describes the hands of the beloved as “llenas de las piedras preciosas jacintos, que son de color de cielo.” Neihter the Vulgate nor the Tanakh comment on the color of the stones, which most modern translators render as Beryl (beryllium aluminium cyclosilicate). However, Abraham ibn Ezra notes in his commentary on the Song of Songs that “some say this stone is the color of the sky” (Bloch 123) a coincidence that suggests, but cannot confirm, that the compilers of the General estoria relied at least in part on Jewish sources in carrying the Vulgate text of the Song of Songs over into Castilian.

In conclusion, the General estoria was the product of an anonymous team of translators working under the direction of Alfonso X, a king with a demonstrated interest in Jewish and Islamic traditions. The work’s Castilian translation of the Song of Songs cleaves very closely to the text of the Vulgate. The majority of instances where it does not are when the translators seem to be accommodating the vernacular sensibility of the Castilian audience. However, in at least two examples the Castilian seems to adapt Jewish approaches to the Song of Songs that contradict Christian doctrine and exegesis. We can only tentatively conclude that Jewish scholars, or Christian scholars familiar with Jewish sources such as the commentaries of Rashi and Abraham in Ezra, adapted material from these sources in their translations because they felt that the positions of these Jewish commentators better served the goals of the translation as they understood it.

Bibliography

- Block, Richard, ed. and trans. Ibn Ezra’s Commentary on The Song of Songs. Abraham Ibn Ezra. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College, Jewish Institute of Religion, 1982.

- Ekman, Erik. “Translation and Translatio: ‘Nuestro Latín’ in Alfonso El Sabio’s General Estoria.” Bulletin of Spanish Studies (2015): 1–16. Print.

- Enrique-Arias, Andrés, ed. Biblia Medieval. <http://www.bibliamedieval.es>

18 October 2015. Web. - Fishbane, Michael A, ed. Song of Songs : The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2015. Print.

- Hailperin, Herman. Rashi and the Christian Scholars. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1963. Print.

- Morreale, Margherita. “Vernacular Scriptures in Spain.” The Cambridge History of the Bible. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969. 465–491. Print.

- Shereshevsky, Esra. “Hebrew Traditions in Peter Comestor’s ‘Historia Scholastica’: I. Genesis.” The Jewish Quarterly Review 59.4 (1969): 268–289. Print.

- Smalley, Beryl. The Study of the Bible in the Middle Ages. Vol. 3rd. Oxford, England: B. Blackwell, 1983. Print.

- Wacks, David A. “Between Secular and Sacred: Abraham Ibn Ezra and the Song of Songs.” Wine, Women and Song: Hebrew and Arabic Literature of Medieval Iberia. Ed. Michelle M. Hamilton, Sarah J. Portnoy, and David A. Wacks. Newark, DE: Juan de la Cuesta Hispanic Monographs, 2004. 47–58. http://hdl.handle.net/1794/8233

This entry is a version of a paper I gave (virtually) at the 2015 Texas Medieval Association, in a session on “Iberian Jewish Exegesis and the Alphonsine Scriptorium organized by Prof. David Navarro and Moderated by Prof. Yasmine Beale-Rivaya (both of Texas State – San Marcos). Prof. Navarro and Prof. Francisco Peña (UBC Kelowna) also contributed papers. The presenters are working together on a collaborative, online digital critical edition of the Biblical material in Alfonso X’s General e grant estoria titled “Confluence of Religious Cultures in Medieval Iberian Historiography: A Digital Humanities Project” and supported by funding from Social Science and Humanities Research Council, Government of Canada