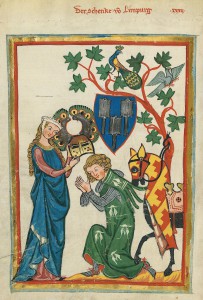

Konrad von Limpurg as a knight being armed by his lady in the Codex Manesse (early 14th century) Source: Wikipedia

Spanish literary history explains the chivalric novel in Spain as a result of the transmission of Arthurian legends developed into prose romances by French writers in the twelfth centuries and imitated by Iberian writers in subsequent centuries. But romance was really more of a Mediterranean phenomenon. Authors working in Greek, Arabic, and various Romance languages all contributed to the development of what we might call the medieval Mediterranean romance during this period. Thus the tradition of chivalric romances of the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that became so popular in the early age of print in Iberia and beyond, such as Tirant lo Blanch and Amadís de Gaula, were part of a pan-Mediterranean culture of romance. In this textual tradition, the lands of the Mediterranean were the stage for the romantic and military exploits of heroes who fought in the name of their beloveds, their kings, and their god. These heroes championed the causes of Islam, Byzantium, and Latin Christendom variously. In the final analysis they championed our need to take a messy, confusing, dangerous world, and have it all make sense, with cut and dried moral values and clear winners and losers.

Arguing over what is chivalric romance and what is not is like arguing over which country can claim Antarctica. It is a political distinction that rests on a narrative which ultimately, like national historiographies, is a fiction. We know very well that literary histories are political instruments that respond to ideologies that may have little or nothing to do with those that informed the authors, works, and aesthetics they pretend to represent. The resulting narratives distort the facts.

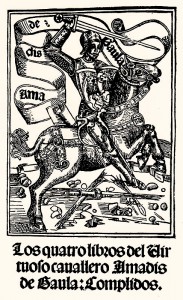

An excellent example is the argument over the origins of the novel and its implications for the study of the so-called chivalric novel. Whether or not the Quijote or Madame Bovary or Middlemarch or The Golden Ass was the first novel is an anachronizing tautology. If it important to establish, for example, that Amadís de Gaula (1507) is the first Spanish chivalric novel (and I am not arguing that it is), then anything that resembles Amadis is also a chivalric novel, and anything that does not was something else, and perhaps less worthy of our attention when we talk about chivalric romance. If it is the year 1300, and Amadis is still over two hundred years in the future, this approach tells us nothing about the literary culture of 1300, a little about that of 1507, and a whole lot about 2015. If Amadis is the yardstick, what do we do with Flores y Blancaflor (ca. 1300), or Cavallero Zifar (ca. 1300), for example? They do not look precisely like Amadís de Gaula, and so are not in the club. I do not say this because I have a personal investment in the recognition of all non-chivalric prose fiction adventure novels, but because I believe we are doing ourselves a disservice by letting these categories determine our approach to the sources.

In this frame, the study of all prose fiction narrative involving a hero bearing arms and mounted on a horse is judged against Amadis, and therefore against certain canonical French romances thought (by a tradition of criticism that has more to do with France and England than with, for example, fourteenth-century Valencia, Zaragoza, or Granada) to be most important in contributing to Amadís and therefore to the genre of chivalric romance, and therefore more prestigious, more authentic, and ultimately a more relevant expression of literary art than other works of prose fiction narrative in which armed horsemen figure prominently. In this game, any work deemed to prefigure Amadís and therefore the Arthurian romance (and really we are talking about those of Chrétien de Troyes) counts, and those works that deviate significantly from this metric do not.

This story of ‘influence’ lets us wall away Arthurian Romance from its Byzantine and Arabic counterparts. Historians can then say that Tirant lo Blanch, for example, is essentially Arthurian with some influence of the Byzantine novel. But what if it that is not how it works? What if affinity and similarity are not the result of ‘influence’ but of something more like ‘co-evolution’ or ‘siblinglry,’ that what we perceive as texts belonging to two or more separate families are really litter mates whose affinity is due not to the ‘influence’ of one on another, but of a shared experience that goes beyond the readings that certain authors had in common. If we are going to theorize the romance in Iberia, let’s use the Mediterranean, not the Atlantic, as the frame of reference.

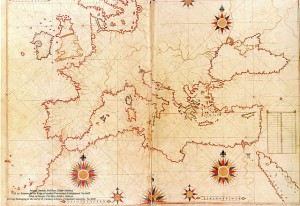

Piri Reis map of Europe and the Mediterranean Sea” by Piri Reis (circa 1467 – circa 1554) – Library of Istanbul University. No:6605. Source: Wikimedia

During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, different strands of literary narrative practice came together to produce a corpus of prose fiction adventure novels that were in large part based on epic traditions as they had been received by current historiography. Chroniclers had been making ample use of cantares de gesta from the Peninsula and beyond in the Christian kingdoms of Iberia and elsewhere. These prosifications of what could only have been considered histories spurred further novelizations of local epic traditions in which the fictional world represented was that of the court where the historiographers worked. These narratives, shaped and transmitted in more popular contexts, were then further novelized by courtly writers whose goal was to shift the symbolic center of the narrative from battlefield to court.

In this new prose fiction, which dealt at length on the amorous and political intrigues of its protagonists and less on exhaustive descriptions of massive battles waged between nations, the poetic forms of courtly poets and the prosaic practice of court historiographers merged. In the case of Arabic (and to a lesser extent in French and in Spanish), the new narrative genres featured poetry interspersed directly within the narrative compositions. But largely it was the sensibilities, the affectations, and to a certain extent the language of love that authors novelized in the new fictions, happily chronicling the exploits of protagonists need not be presented as historical.

If we widen the lens beyond the transpyrennean route that brought Arthurian material to the Iberian Peninsula, and reframe the definition of the textual practice in question, a different picture begins to emerge. In this one, writers around the Mediterranean move from chronicle and poetry to courtly prose fiction narratives that combine elements of both while giving expression to courtly values that span correct conduct, military skill (but not necessarily large scale military conflict). If the chronicle gives narrative form to the events that transpire during the reign of a given monarch or a given royal house, the romance gives narrative form to the social and political ideals of the political community that supports the royal power. This is true whether the backdrop is Rome, England, France, or elsewhere. This functional rather than genetic description of the romance authorizes us to look beyond the usual suspects in putting together a picture of how Iberian romances (however we define them) fit into the wider frame of literary practice in the medieval mediterranean.

If we just stick to prose fiction written about knights and their adventures, we have an interesting group of narratives that emerge in the thirteenth century in the Mediterranean. Sharon Kinoshita introduces this problem in a recent article in PMLA* in which she brings ‘to light’ a handful of what we might call romances written in non-French areas of the Mediterranean such as Anatolia, Byzantium, and Egypt. These narratives all share key features with French and Spanish romances dealing with what I will call the funky three: Rome, Britain, and France. They are the Turkish Düstürname, (‘Tale of Dustur’), the Byzantine Digenis Akritas (‘Two-blooded Border Hero’), and the Arabic Sirat Antar (‘Tale of Antar’). To these, I would add the Andalusi Ziyad ibn `Amir al-Quinani. Taking away the mandatory Arthurian point of reference, these heroes and the tales that describe their adventures all perform similar cultural work: they adapt epic traditions, sometimes quite loosely, to the task of representing courtly ideals in the military, political, and romantic spheres.

In sum, and following Kinoshita’s lead, I am proposing a new framework for the study of the medieval Mediterranean adventure novel in Iberia that does not draw a straight line between Chrétien de Troyes and the Quijote via Amadis. Rather, I propose a field of inquiry that spans the Mediterranean and focuses on the co-evolution of courtly prose narrative fiction as a regional expression of a regional courtly culture of elites. These courtly elites, despite linguistic and religious differences, shared a common experience that found expression in the fictional tales of warriors and ladies whose adventures were the canvas on which authors gave voice to the political, social, and religious concerns of the day.

* Kinoshita, Sharon. “Medieval Mediterranean Literature.” PMLA: Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 124.2 (2009): 600–608.

This post is a preliminary version of a paper I’m giving at the 2015 MLA in Vancouver BC, in session 12a, “Medieval Literary Theory: Europe and Beyond.” Thanks to Prof. Jill Ross (U Toronto) for organizing the session.