[This post includes material later revised and expanded in Double Diaspora in Sephardic Literature: Jewish Cultural Production before and after 1492 (Indiana University Press, 2015)]

Jews from Spain had been settling in the Ottoman Empire since at least the fourteenth century, and after the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492 the populations of Sephardic Jews in the cities of the Ottoman Empire increased significantly. Messianism was in the air in those days, and Jewish hopes of returning to Zion in anticipation of the arrival of the Messiah coincided with Ottoman imperial designs on Palestine. After the Ottomans annexed Palestine in 1516, Jewish, and especially Sephardic immigration to Palestine surged, fueled both by favorable immigration policies and by messianic fervor. The reconstruction and settlement of Tiberias (an ancient site prophecied to be the arrival point of the messiah) by Don Joseph Nasi during the 1550s, against the backdrop of the gathering of messianic kabbalists in nearby Safed at the same time, provides us with a snapshot of the twin discourses of de-diasporization: the prophetic and the political.

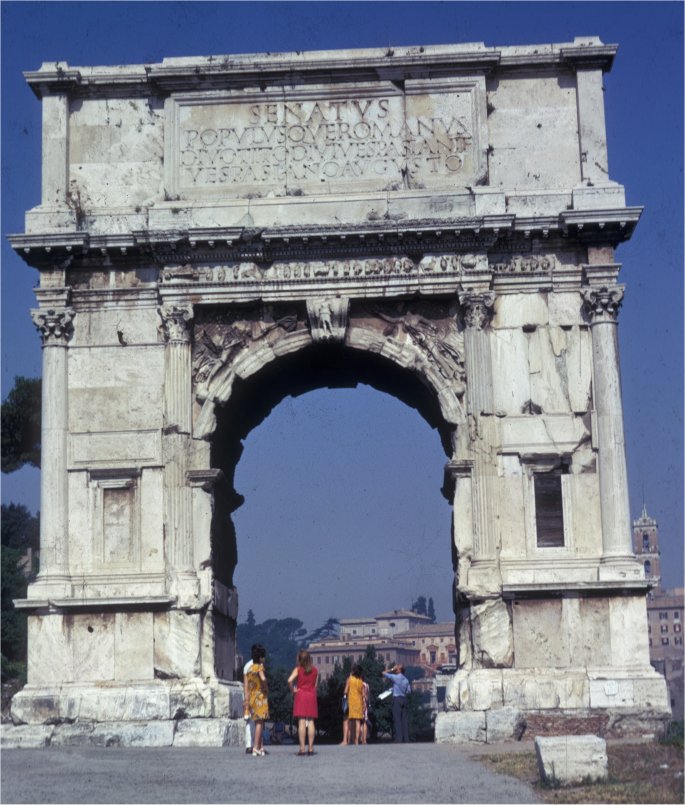

The expulsion from Spain was a collective trauma superseded in Jewish history only by the destruction of Jersualem by Titus Andronicus in the year 70 CE. Since Roman times, the rabbis had developed a sophisticated (if varied) doctrine of galut (literally ‘exile’) or diaspora that both explained the loss of a sovereign Jewish homeland and provided a structure for community governance and daily life both as colonial subjects in Roman Palestine (in the Talmudic tractate Avodah Zarah) and as a diasporic minority elsewhere. Expulsions and persecutions of Jews in various countries over time were fitted into this scheme, rationalized as divine punishment for the Jews’ lax observance of religious law or excessive acculturation, latter-day examples of the golden calf episode in Exodus.

Sephardic writers who witnessed (directly or otherwise) the events of 1492 gave voice to the trauma of the expulsion and the privations suffered by the expelled, mostly following rabbinic tradition but also drawing more modern looking historical parallels with Roman and medieval examples. It was, after all, the sixteenth century, and the world was at the brink of modernity, a place characterized increasingly by global trade networks, rapid diffusion of ideas in print, and complex patterns of international migrations. Sephardic reactions to expulsion in the 1500s were bound be be different from Judean reactions in the 100s.

Solomon ibn Verga, author of the anthology of persecutions and expulsions titled Shevet Yehudah (Rod of Judah), includes a number of vignettes of what befell the exiles:

Some of them sought a path by sea amongst turbulent waters, but there also the hand of the Lord was with them to confound and exterminate them, for many of them were sold as slaves and servants in all of the lands of the gentiles. Many sank into the sea, drowning, at last, like lead. Others came to perish in fire and water, as the ships caught fire, and thus the fire of the Lord burned against them. (ch. 51)

I heard from the mouths of one of the elders who went out of Spain that in one ship they declared an epidemic of plague, and its captain threw the passengers onto the beach in an unpopulated area, where the majority of them died of hunger. Some decided to go on foot to find a settlement. One of those Jews, his wife, and their children decided to go; his wife, not accustomed to walking, grew weak and perished. The man and his two sons that he had with him also passed out from hunger and, when he regained consciousness, found his two sons dead…. (ch. 52)

Ibn Verga also goes into depth in examining Jewish-Christian relations and what it means to be a member of a diasporic population struggling to stay in the good graces of a temporal power that holds Judaism and often Jews themselves in open contempt. In a fictional debate between the Spanish King and delegates from the Jewish community, the King accuses the Jews of being dishonest thieves, who have been welcomed into Spain only to repay their hosts with crimes and dishonesty. The delegates respond:

As to the question of thievery, what can we say? Certainly we are like rats: one of them eats the cheese and all of them bear the blame. Naturally, there are good and bad [Jews], but the sins are born by all of us. Are there not robbers and thieves among the Christians? Despite the fact that excellent and superior personal qualities are to be found among the Christians, we still see daily hangings for robbery and thievery. But sovereignty covers up many things, like the veil on the woman covers up many imperfections. Diaspora is the opposite, for it uncovers and makes a stain as small as a mustard grain seem as large as the orb of the sun. (ch. 8 )

The neo-realpolitik in Ibn Verga’s historical imagination represents a new direction in Jewish history. On the surface he respects the prophetic tradition. He explains that the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand and Isabel act merely as instruments of Providence. But he also brings a new, more modern approach, experimenting with representations of the Christian perspective and analyzing the political processes that drive key events.

People reacted differently to the events described by Ibn Verga. Historically,very few Jews emigrated to Palestine from the diaspora, and those who did were typically supported by charitable donations from abroad, there being little to no Jewish commerce or industry in the Holy Land. In the Ottoman period, the more favorable relations between the Sultans and his Jewish subjects resulted in an increased Jewish presence in Palestine. Jewish immigration to Palestine was only a trickle compared to the far larger settlements in important trade centers such as Salonika and Constantinople, but for Jews, Palestine had unparalleled historic and spritual appeal. Some sought refuge in the protection of the Ottoman Empire, seeking to recreate the life they had enjoyed in Spain. For them, the move to Palestine was an ironic double diaspora, a return to the days of Roman Palestine, living in the zionic homeland under a foreign king — a situation, we should remember, that was in perfect accordance with the rabbinic throught of the times.

Two reactions to exile

We can discern two different reactions to the expulsion from Spain in the intellectual and political gestures made by various Sephardim during the sixteenth century. The common response was to turn inward, to shun the vernacular culture and cosmopolitanism that many rabbis interpreted as having invoked God’s punishment of expulsion. Others sought to recreate their Spanish experience by taking full advantage of the benevolence of the Ottoman Sultans and gaining prominence at the Sublime Porte (the court of the Sultan) just as they once had at the courts of Christian monarchs in Spain and Portugal. Many Sephardim who lived in Palestine had spent some time living as conversos (Jews converted to Catholicism) in Spain, Portugal, and in Spanish territories in Italy. This experience had given them a bittersweet taste of life as a member of the dominant culture. They were more familiar with the intellectual and religious life of the Christian majority than their unconverted Jewish counterparts. As we will see, Some conversos who then returned to Judaism in Italy or in Ottoman lands suffered terrible guilt for having chosen an insincere conversion over expulsion or martyrdom at the hands of the Inquisition. This drove some to an extreme form of pious ascetisicm that ironically bore clear marks of Christian influence. For other ex-conversos, the experience made them hungry for more — not more Christianity, but more of the relative freedom and power that comes with a majority identity. Some toward God, others toward material and political security.

Joseph Karo (Toledo 1488 – Safed 1575) was one of those who turned toward God. Karo was an highly respected expert in Jewish law, and is best known as the author of the definitive synthesis of Jewish law, the Shulkhan Arukh or ‘Set Table.’ He migrated from Spain to Portugal to the Ottoman Empire, passing through Salonika and Constantinople before settling in Safed in Palestine. There he joined a group of pious mystics who concerned themselves with putting the spiritual house of Jewry in order. For Karo and the circle of mystics who had gathered at Safed in northern Palestine, the expulsion was divine retribution for the sins of the Sephardim. Their project was the spiritual refinement of all Jews, to be achieved through rigorious observation of the law and tireless pursuit of the mystical dimensions of the Torah and the commandments. Karo and his companions dedicated themselves to the tireless and compulsive refinement of religious law and mystical practice. For them, the road to redemption was the path of righteousness, exacting fulfillment of the divine commandments and rigorous contemplation of the nature of God. They were not concerned with reestablishing Jewish political power — this would be accomplished only after the arrival of the messiah. And the best way to prepare for this, according to Karo and his circle, was through fastidious observation of the commandments and penetrating contemplation on their mystical meaning.

Karo recorded a series of visions in which the shekhina (God’s feminine aspect according to kabbalistic doctrine) spoke through him. These visions, which are more like a series of lectures on biblical interpretation, promote an extreme ascetism virtually unkown in prior Jewish tradition (it is possible that an influx of conversos who had returned to Judaism in the Ottoman Empire had introduced some ascetic practices from Spanish Catholicism)(Goldish) . Karo summarized these in the introduction to his Magid Meisharim (‘Preacher of Righteousness’):

Be careful to avoid taking taking pleasure while eathing meat and drinking, or while partaking of any other kind of enjoyment. Act as if a demon were forcing you to eat this food or indulge in the enjoyable activity. You should very much prefer it were possible to exist without food and drink altogether, or were it possible to fulfill the obligation of procreation without enjoyment. (Fine 56)

The particular flavor of mystic aseticism practiced by Karo and his associates in Safed was a novelty in the Jewish context, bringing to a head a tendency that had been percolating in Sephardic religious practice at least since the anti-Jewish violence of 1391 in Spain (Goldish, “Patterns”). The expulsion had kicked off a messianic fervor that lead some, most notably Isaac Abravanel (leader of Castilian Jewry and father of Leone Ebreo, the author of the Dialogues of Love) to predict its arrival in 1503 (Netanyahu 216-226). This movement died out after the 1540 arrival predicted the self-fashioned messiah Solomon Molkho did not come to pass. In the Ottoman Palestinian context, messianic hopes were further stirred when Suleyman the Magnificent rebuilt the walls of Jerusalem between 1536 and 1542 (Levy 20-21). Afterward, kabbalists such as those gathered at Safed changed course, urging a general purification of Judaism and of Jews worldwide in order to hasten the arrival of the Messiah. And while their messianism was not as urgent at that of the previous century, they introduced an important innovation in Jewish messianism: Karo himself was the first to suggest that it was human action, and not divine action, that would bring about the coming of the messiah and the redemption of the Jews (Elior 22). They took on personal responsibility for what they perceived as the moral failings of the exiled Sephardim and strove for a spiritual perfection that would pave the way for the coming of the messiah through the mystical work of reuniting the shekhina with her lover.

Karo’s student Moses Cordovero likewise taught that redemption—allegorized in the reunion of the King (God’s masculine aspect) with his Queen (God’s feminine aspect)—depends upon human actions. When we do good, we draw them together; when we sin, we drive them apart (Jacobs 37). The more good deeds we perform, the sooner comes the Messiah. Simple.

Cordovero wrote a guide to making this happen called The Palm Tree of Deborah. According to Cordovero, when we do good, we do good not just to ourselves to also to God, who benefits from our actions:

In the acts of benevolence man carries out in the lower world he should have the intention of perfecting the upper worlds after the same pattern and this is what is meant by doing lovingkindness to the creator. (Cordovero 91-92)

Likewise, bad deeds do harm to the Shekhina, God’s feminine aspect in Kabbalistic thinking:

the flaw of his deeds pushes away the Shekhinah from above. He should fear to cause this great evil of separating the love of the King from the Queen. (Cordovero 117)

So, when we imitate a given divine trait (as revealed in Scripture), we act not only on this world but also upon the divine world. The good deed of healing the sick heals not only the sick person on Earth, but also helps to cure the sickness of the Shekhina in heaven, who is lovesick due to her separation from the King (God). Cordovero therefore instructs us to

visit the sick and heal them. For it is known that the Shekhinah is love-sick for the Union, as it is written: ‘For I am love-sick.’ Her cure is in the hands of man who can bring her the good medicine she requires, as it is written: ‘Stay me with dainties, support me with apples’ [Song of Songs 2: 5]. (Cordovero 94)

This messianism was not in the least political —on the contrary, Jewish messianic doctrine had long held that Jewish sovereignty would not return to Zion until the messiah had already arrived. But not all Sephardic Jews were content to defer sovereignty until the messianic age, nor to dedicate themselves, as did Karo and the Safed mystics, to ritual purification in hopes that it might speed the messiah’s arrival. At least one man, as if in response to Ibn Verga’s lament on the travails of diaspora, sought to take matters into his own hands.

Don Joseph Nasi and the Tiberias Experiment

While Karo and his mystics focused their energies inward, penetrating deep spiritual mysteries, his namesake Don Joseph Nasi (formerly João Miguez), the Duke of Naxos and de facto leader of Ottoman Sephardi Jewry in the mid-sixteenth century, focused on temporal power. In 1561 Don Joseph negotiated a perpetual land grant consisting of the ancient Galilean city of Tiberias and its surroundings, with the aim of rebuilding the ruins of that city and establishing there a silk and textile operation similar to the one previously established in nearby Safed (on the opposite shore of the Sea of Galilee).

From the Ottoman point of view, Jewish migration to Palestine followed the customary practice of incentivizing religious minorities with specialized commercial and administrative skills to settle in provincial centers. Both parties were served: the Sephardim enjoyed advantageous tax rates and lucrative concessions, while the Ottomans both broadened their tax base and hedged their political interests vis-à-vis indigenous Arab leadership. In the case of Palestine, a Jewish settlement in the Galilee served to bolster Ottoman interests against those of local Arab sheikhs, who found common cause with the Franciscan Dean against Don Joseph. The Dean, Bonifacio Stefano Ragusi, wrote against Don Joseph’s (whom he refers to as João Miguez, his Christian name) plans in a letter. He writes that he fears that the Jewish settlers will try to turn St. Peter’s church into a synagogue:

From the Ottoman point of view, Jewish migration to Palestine followed the customary practice of incentivizing religious minorities with specialized commercial and administrative skills to settle in provincial centers. Both parties were served: the Sephardim enjoyed advantageous tax rates and lucrative concessions, while the Ottomans both broadened their tax base and hedged their political interests vis-à-vis indigenous Arab leadership. In the case of Palestine, a Jewish settlement in the Galilee served to bolster Ottoman interests against those of local Arab sheikhs, who found common cause with the Franciscan Dean against Don Joseph. The Dean, Bonifacio Stefano Ragusi, wrote against Don Joseph’s (whom he refers to as João Miguez, his Christian name) plans in a letter. He writes that he fears that the Jewish settlers will try to turn St. Peter’s church into a synagogue:

The infidel jew Zaminex [Don Joseph Nasi —apparently the name used here is a distortion of his Portuguese name, João Miguez] hoped to expel the snakes [Muslims] and settle his brethren the poisonous vipers [Jews] there, to turn our church into a synagogue. In order to stand in the breach, I consulted in utmost secrecy with Rustem Pasha and Ali Pasha [governor of Damascus] and they promised me that no such thing would come to pass during Sultan Suleiman’s lifetime. Their deeds matched their words. (David, Come 32; original Latin in Ragusi, Perenni 269)

What must have been most disturbing to Don Joseph’s enemies in the region was not the mere fact of Jewish immigration, but the unmistakably political nature of the project, a permanent Jewish settlement in the very place where, according to tradition, the messiah would make his first appearance on earth. It was as if these settlers wanted a front-row seat for the redemption, and they were willing to camp out for it, not just all night, but indefinitely.

While to the Ottomans the Sephardim brought administrative skills and extensive business and social networks, the Sephardi discourse of immigration to Palestine was heavily prophetic: ejected from their ancestral homeland Iberia, they sublimated the longing for Spain into a Biblical-flavored discourse of the return from diaspora to the promised land. As favorable as conditions were for them in Salonika or Constantinople, only Zion (even if it came in the form of Ottoman Palestine) could fill the symbolic void that the loss of Sepharad had opened. For them Ottoman Palestine became, in a sense, the homeland they had lost in Spain.

For a community that for centuries had defined itself as a diaspora, for the great majority of whom the scriptural and prophetic homeland of Zion was more symbolic than concrete, what must the prospect of return have been like? It is tempting to draw parallels with the example of post-World War Two Zionism, in which it was a simple symbolic calculus for victims of the Nazis to reclaim the biblical promise of sovereignty as a bulwark against further abuses. But Ottoman Palestine was another time and place, and Joseph’s Tiberian experiment must be read against its own particular background.

Ottoman annexation of Palestine in 1516 opened the gate for increased Jewish immigration to the ancestral homeland. Previous Jewish migration to Palestine was exclusively spiritual, and the olim (those who had ‘gone up’) were supported by charitable donations from the diaspora. This was also the case with the kabbalists settled in Safed, who enjoyed the patronage of diaspora communities as well as that of the powerful Doña Gracia Nasi and her nephew Don Joseph Nasi.

Don Joseph’s Tiberian project differed from other patterns of Jewish settlement in the Ottoman Empire in that it was political as opposed to merely mercantile. In other areas of the Ottoman Empire the Jews pursued commerce, worked as imperial functionaries, or as artisans. In Tiberias, Don Joseph’s plan was long-term and vertically integrated: he planted mulberries outside the city to support silkworm farming, which in turn provided the raw materials for an offshoot of the textiles business that was flourishing in Salonika and to a lesser extent in nearby Safed (some 15km away). Joseph’s aim was to build a durable Jewish settlement that would anchor the growth of a Galilean Jewish fiefdom within Ottoman Palestine. This amounted to a geographic projection of Don Joseph’s influence at the Sublime Porte, the Sultan’s court at Constantinople.

Tiberias was quite near Safed, which had been a thriving center of religious studies for nearly a hundred years. By the time that Joseph began to rebuild the walls of ancient Tiberias, renowned kabbalists such as Isaac Luria, Solomon Alkabetz, and Moses Cordovero were revolutionizing religious life throughout mediterranean Jewry. They cultivated extreme ascetic practices and wrote texts that would become seminal works of kabbalah. The urgency with which they worked and the intellectual ferment that characterized their small circle of mystics was nearly unparalleled in Jewish history.

During the 1560s, while Don Joseph worked to establish his colony, Tiberias and Safed were like twin cities, each expressing a different reaction to the Sephardic diaspora. Some adopted a diasporic apolitical (though one might argue political in its non-engagement) posture, making sovereignty a religious ideal while simultaneously evolving sophisticated strategies to thrive as a non-sovereign nation. We should not forget that Karo was unsurpassed in his systematization of Jewish law. Far from a sloppy ecstatic, he was a compulsive, cerebral mystic. He is not like al-Ghazali in that he was equally rigorous as a lawyer and as mystic. While Don Joseph’s reaction was more political, it shared the industriousness that characterized Karo’s thought. Both were examples of the Sephardic reaction to diaspora, of turnng and re-turning (Tölölyan) to Zion.

Works Cited

- David, Abraham. To Come to the Land: Immigration and Settlement in Sixteenth-Century Eretz-Israel. Tuscaloosa Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 1999. Print.

- Elior, Rachel. “Exile and Redemption in Jewish mystical thought.” Journal of the Interdisciplinary Study of Monotheistic Religions (JISMOR) 4 (2008): 11-24.

- Fine, Lawrence. Safed Spirituality. New York: Paulist Press, 1984.

- Goldish, Matt. “Patterns in Converso Messianism.” Jewish Messianism in the Early Modern World. Vol. 1. Dordrecht: Kluwer, 2001. 41-63.

- Ibn Verga, Solomon. Sefer Shevet Yehudah. Ed. Azriel Shohet. Jerusalem: Mossad Bialik, 1946.

- —. La vara de Yehudah. Trans. María José Cano. Barcelona: Riopiedras, 1991.

- Jacobs, Louis. “Introduction.” The Palm Tree of Deborah. Trans. Louis Jacobs. London: Valentine Mitchell, 1960. 1-39.

- Levy, Avigdor. The Sephardim in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton: Darwin, 1992.

- Netanyahu, B. Don Isaac Abravanel, statesman & philosopher. 5th ed. Ithaca N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1998.

- Ragusino, Bonifacio Stefano. Liber de Perenni Cultu Terrae Sanctae. Venice, 1875.

- Roth, Cecil. The House of Nasi: the Duke of Naxos. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1992.

- Tölölyan, Khachig. “The Contemporary Discourse of Diaspora Studies.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 27.3 (2007): n. pag. Accessed 20 July 2010.

This post was made possible with support from the UC Mediterranean Studies Research Project/Mediterranean Seminar and forms the basis of a roundtable presentation given at the The Mediterranean Seminar (UC Multi Campus Research Project), Spring Workshop Roundtable: ‘Reconstructing the Past.’ UC San Diego, 3 Feb 2012.

Your feedback and comments appreciated. Use comment field below or email me.