This is the slidecast from a Work in Progress talk I gave last week at the Oregon Humanities Center, where I was Ernest Moll Fellow in Literary Studies during Winter term 2011. You can also listen to the .mp3 here.

Tag Archives: medieval Spanish literature

“Great book, but is it really Spanish?”

[This post includes material later revised and expanded in Double Diaspora in Sephardic Literature: Jewish Cultural Production before and after 1492 (Indiana University Press, 2015)]

See also the related article published in Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies [Open Access postprint version]

Popular audiences in Jewish communities across the world are practically addicted to images of Spanish Jewry’s “Golden Age.” The idea of a Jewish community that was rich, powerful, and intellectually talented has been pretty compelling to the modern Jewish imagination. That whole expulsion/inquisition thing at the end kind of messes things up, but we’ll leave that aside for the time being. As far as most modern Jews are concerned, Spain was the best keg party ever, and like most great keg parties, it got ugly at the end.

The point here is that for the most part, world Jewry is happy to claim the Sephardim as a shining example of Jewish cultural achievement. This was not really ever in question as long as I have been paying attention. But working as a Hispanist and reading a lot of studies by Spanish scholars on Spanish Jewish (Sephardic) topics, I began to wonder if Spain was also eager to claim the Sephardim as Spanish. One way to find out is to read what literary historians have to say about Jewish authors who lived and wrote in Spain.

In two recent posts I wrote about the medieval Sephardic poet Todros Abulafia (late 1200s) and some of his modern critics’ opinions of Abulafia’s troubadour-flavored poetry. In this post I would like to discuss a related case, that of the Sephardic author Shem Tov (‘Santob’) ben Isaac Ardutiel of Carrión (mid 1300s). Like Todros Abulafia, most Jewish authors at this time wrote almost exclusively in Hebrew. Many Jewish intellectuals translated works from Arabic and occasionally Hebrew into Spanish, Catalan, or Portuguese, but when they did their own work it was almost exclusively in Hebrew. As far as we know, Shem Tov Ardutiel is the only Jew of his time to write an original book in the vernacular, the Proverbios Morales (‘Moral Proverbs’).

The book is a collection of wise sayings in verse, an original work of what scholars like to call ‘wisdom literature,’ which during the Middle Ages was a well-cultivated genre. Medieval writers had good models for their books of wisdom literature in the Biblical Proverbs and Ecclesiastes, as well as Greek and Latin collections of philosophical musings, proverbs, aphorisms, and exemplary tales. Shem Tov’s Proverbios was an original, innovative work that incorporated a variety of sources from the bible, rabbinical literature, and folklore. It was not, however, in any way a Jewish text. That is, it did not cite either the Hebrew Bible or the Rabbis, and did not present any specifically Jewish lessons. It was basically a secular book of wisdom or popular philosophy, written in Castilian, the dialect that would eventually come to be called Spanish.

Without going into the question of why medieval Jews didn’t write original work in Spanish (though I write about it a little bit in here on pages 183-185), I would rather like to look at what Shem Tov’s Spanish readers had to say about this rare bird of a book, and whether they considered it (and him) to be, like them, Spanish.

A little caveat: in the 1300s, there was, strictly speaking, no ‘Spain.’ The idea of Spain as a nation state comes later, some say with the reign of the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella, some say even later. So to refer to any author writing in Toledo or Barcelona or Seville in 1300 as ‘Spanish’ is a convenient anachronism. Shem Tov was a subject of the Crown of Castile and León, and he probably considered himself to be sefardí, or a Jew from the Iberian Peninsula, but he had no notion of Spain as a modern nation state and could not have considered himself Spanish in that sense. My question is, do his Spanish readers consider him Spanish?

A while back I wrote an article titled “Is Spanish Hebrew literature ‘Spanish?’” in which I looked at what Spanish scholars of Hebrew had to say about the Hebrew literature written in Spain during the Middle Ages. Did they consider it to be part of their national heritage? Did they view the Jewish authors who wrote in Spain as part of their nation’s medieval past or where they part of a foreign culture that happened to live in Spain?

Like most questions, the answer depends on whom you ask. Shem Tov himself seems to have anticipated this problem, and in the introduction to his work he asked his readers not to judge his work by the religion of its author. He says that even if his book was written by a Jew, it’s still worthwhile. Can you imagine an American Jewish author writing these lines today?

Non val el açor menos por nasçer de mal nido,

nin los enxemplos buenos por los dezir judíoThe falcon is not worth less for having been born in a poor nest

nor the good proverbs for having been told by a Jew

So it seems Shem Tov imagined that Christian readers might think poorly of his work because of his religion. His fears were not always realized. Early on, Spanish literati praised the Proverbios. One of the most influential figures in the Spanish literary scene in the 1400s, the Marquis of Santillana, called Shem Tov a ‘very great troubadour poet’ (“muy grant trobador”).

In modern times, Shem Tov’s readers are divided on the question of the “Jewishness” or “Spanishness” of both the man and his book. As in the case of Todros Abulafia’s Israeli critics, a lot of this division is tied to contemporary politics and professional formation.

José Rodríguez de Castro, wrote during the late 1700s, when the Spanish Inquistion was still officially on the books (it was abolished in 1834). Like Santillana, he praises Shem Tov’s poetry, calling him ‘one of the most famous troubadour poets of his time’ (“uno de los Trobadores más célebres de su tiempo”). However, he also thought that Shem Tov was a converso, or a Jew converted to Christianity. It may not have been a good idea in Rodríguez de Castro’s day to celebrate a Jew as a great national poet.

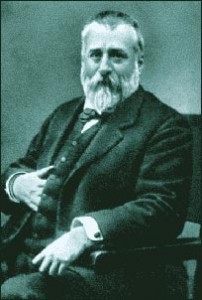

José Amador de los Ríos was a liberal 19th-century scholar who wrote the first major Spanish-language treatise on Spanish Jewry. He makes it clear that Shem Tov is a national poet, in fact ‘the most accurate interpreter of the general feeling of the Castilians’ of his time’ (“el más fiel intérprete del sentimiento general de los castellanos”)

On the other side of the aisle, the rather more conservative Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo, perhaps the most influential intellectual of his time, exoticizes Shem Tov and places him outside of the national culture. Far outside:

[His work] has an oriental flavor so distinct, both in its language and its imagery, that at times it seems to have been written originally in Hebrew and later translated by its author into Castilian. . . . it is difficult to believe that this book, so profoundly Semitic, so denuded of all classical and Christian influences, might have been created in the Campos region of Castile.

tiene un color oriental tan marcado, así en la lengua como en las imágenes, que á ratos parece escrita originalmente en hebreo y traducida luego por su autor al castellano….cuesta trabajo creer que este libro, tan profundamente semítico, tan desnudo de toda influencia clásica y cristiana, haya nacido en tierra de Campos.

Under Franco, this orientalizing of Shem Tov becomes the norm. In 1943 Juan Hurtado y Jiménez de la Serna writes of Shem Tov’s ‘oriental-flavored exotic character’ (“carácter exótico de sabor oriental”), and Juan Luis Alborg (writing in 1970 in the US but publishing in Spain) says that Shem Tov’s style is ‘unique to Hebrew literature’ (“peculiar de la literatura hebrea”), and, it follows, out of place in Spanish literature.

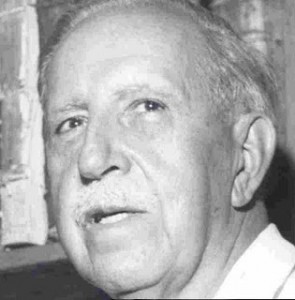

In exile from Franco’s Spain, Américo Castro, whose controversial theory of convivencia (Spain’s essential Semitic and Christian hybridity) continues to divide scholars of Spanish culture, combines both approaches. For him, Shem Tov is a Semitic and therefore authentically Spanish author. On the one hand, the folksy tone of his Proverbios is ‘Sancho Panza-like’ (“sancho-pancezco”) (1948); On the other, he writes that Shem Tov is a writer who ‘gazes steadily toward the East, and not toward Christian Europe’ (“sigue sigue mirando hacia el Oriente, y no a la Europa cristiana”) (1952).

The debate over Shem Tov’s “Spanishness” or “Jewishness” is just one small piece of the much larger discussion of the role of Spain’s Semitic cultural history. For those outside of Spain, it is a simple matter to celebrate the accomplishments of Spain’s Jews (maybe too simple at times). But for Spaniards themselves, it’s complicated. There is a lot of history, much of it unpleasant, surrounding Spain’s Jews.

For hundreds of years, Spanish identity was not simply about being Catholic, but about not being Jewish or Muslim (think about pork everywhere all the time). From 1478 to 1834 there was a government agency (the Spanish Inquisition) whose only job was to enforce this identity. And despite various experiments in religious freedom during the late 1800s and early 1900s, Spain did not disestablish official Catholicism until 1978. Given this history, it is logical that there would be some ambivalence in embracing Sephardic culture as part of the national heritage.

Nowadays, some thirty years after Franco, things have changed a great deal. In 1992, King Juan Carlos officially welcomed the Sephardic Jews to apply for fast-track citizenship along with Latin Americans, Filipinos, and other ex-colonials (but not Muslims descended from those expelled from Spain). There has been a bit of a Renaissance of Jewish life in Spain, and the numbers of Jewish immigrants to Spain from North Africa and elsewhere have been bolstered by a slow stream of Catholic Spaniards who have converted to Judaism.

The Jewish ‘question’ in Spain continues to be lived and debated, and part of this process is an ongoing rethinking of the role of Spain’s Jews in the story of Spain’s history. Shem Tov’s Proverbios is not widely read by Spaniards today. He does not generally show up in high school literature classes, and there are no popular editions of the Proverbios for sale in bus-stop kiosks. His book may never gain wide appeal, but it will be interesting to see if and how Spanish readers return to him and to other Iberian Jewish and Muslim authors as they continue to rethink their nation’s cultural heritage.

Bibliography:

- Alborg, Juan Luis. Historia de la literatura española. Madrid: Editorial Gredos, 1970.

- Amador de los Rios, José. Historia crítica de la literatura española. Madrid: J. Rodríguez, 1861.

- Ardutiel, Shem Tov ben Isaac. Provberbios morales. Ed. Paloma Díaz Mas and Carlos Mota. Madrid: Cátedra, 1998.

- —. The moral proverbs of Santob de Carrión: Jewish wisdom in Christian Spain. Trans. T. Anthony Perry. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1987.

- Castro, Américo. España en su historia cristianos, moros y judíos. Buenos Aires: Editorial Losada, 1948.

- —. “Un aspecto del pensar Hispano-judío.” Hispania 35.2 (1952): 161-172.

- Hurtado y Jiménez de la Serna, Juan. Historia de la literatura española. Madrid: Tip. de la “Revista e arch., bibl. y museos”, 1921.

- López de Mendoza, Iñigo (Marqués de Santillana). Obras completas. Ed. Ángel Gómez Moreno & Maximiliaan Paul Adrian Maria Kerkhof. Madrid: Fundación José Antonio de Castro, 2002.

- Menéndez y Pelayo, Marcelino. Estudios de crítica literaria. Madrid: Sucesores de Rivadeneyra, 1893.

- Rodríguez de Castro, José. Biblioteca española. Madrid: Imprenta Real de la Gazeta, 1781.

This post was made possible with the support of the Oregon Humanities Center, where I am currently Ernest G. Moll Faculty Fellow in Literary Studies. It grows out of my current book project, Double Diaspora in Sephardic Literature 1200-1600.