There is very little manuscript evidence of the popular (non-courtly) literature of al-Andalus (Muslim Spain). For this reason it is difficult to assess its importance for the development of Castilian literature, and more broadly, for our understanding of medieval Iberian literary practice as an interlocking set of systems that includes a number of linguistic, religious, and political groups. Ziyad ibn ‘Amir al-Kinani (Granada, 1234) is a work of Andalusi popular fiction that sheds new light on the reception of Arthurian material in the Iberian Peninsula. Ziyad in particular is a fascinating hybrid of Arabic epic, popular Arabic tale, and Chivalric romance. It is the first example of an original work of prose fiction written in Iberia to make use of Arthurian material, one that predates the Castilian translations of Arthurian texts by nearly a century.

Ziyad ibn ‘Amir al-Kinani

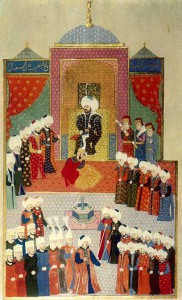

Ziyad is the tale of the adventures of the eponymous hero Ziyad ibn ‘Amir al-Kinani and is set in a flashback at the court of the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid, where the hero is being held captive. Ziyad has been summoned by the Caliph to regale him with stories of his own adventures, in a narrative frame derived from the 1001 Nights and familiar to readers of medieval Castilian literature from the thirteenth-century work Calila e Digna, and later from Don Juan Manuel’s Conde Lucanor. The character Ziyad ibn ‘Amir al-Kinani is not historical. However, as we will see, the author took pains to situate the fictional world of Ziyad within the historical and literary traditions of the the Arab Islamic world.

Sirat Antar: Antarah and Abla depicted on a 19th-century Egyptian tattooing pattern (Source: Wikipedia)

Ziyad and Arabic literary tradition

Much as the chivalric Romances in Western Latin tradition are linked to earlier chansons de gestes and classical epic material (Brownlee Scordilis 254; Fuchs 39) Ziyyad ibn ‘Amir is likewise in some ways an evolution of the popular Arab epic (sira), beginning with the ‘Ayam al-Arab, the account of the first battles of Muslim expansion protagonized by Muhammad and his companions. By the thirteenth century a second generation of sira develops, one that recounts tales of later heroes of Islamic expansion and their struggles with enemies in the Islamic world, Byzantium, and against the Franks (Latin Crusaders). These include the Sirat Dhat al-Himma, and Sirat al-Zahir Baybars, that flourished in Arabic during the time when Ziyad appeared (Heath, “Other Sīras” 327–328).

The sirat were popular oral epic traditions that produced little in the way of literary manuscripts until modernity. This is an important fact in understanding the relationship of Ziyad vis-a-vis the medieval novel in French and Spanish. While the chivalric romance has its roots in oral epic traditions, it evolves into a courtly literary tradition relatively early, while the Arab epic does not. This may be because vernacular literature does not develop significantly in Arabic until much later than in the romance languages.

2014 production of 1001 Nights by Center for Puppetry Arts, Atlanta (Source: Flying Carpet Theatre Co.)

The other Andalusi popular literary texts of the time, such as the 1001 Nights, and its Western variant the 101 Nights, were set at court, but were in no way a courtly product. Rather, they reflected the values of mercantile society, and populated the court of Harun al-Rashid with merchants, artisans, and other members of the middle class (Sallis 1; Ott 260). Ziyad shares the popular linguistic features with the 101 Nights (Ott 266–267), but shows us a world populated with knights and ladies and the occasional slave, a world that more resembles that of the French chivalric romance than the 1001 Nights, with the key exception of its being set in the Muslim East. In this way, Ziyad is a sort of hybrid of the Arab epic, the chivalric novel, and the popular Arabic narrative Nights tradition.

Ziyad is more like the heroes of the chivalric novel in that his excellence is a reflection of his aristocratic background, and as such reinforces the current social order, which is typical of medieval romances (Auerbach 139; Segre 139; Brownlee Scordilis 253). This is perfectly logical when one considers the authorship and audencies of the texts: the popular sirat were composed and transmitted orally, and have very few medieval manuscript witnesses. The same can be said for the Castilian epic Cantar de Mio Cid, which is thought by many critics to be of popular origin. Popular audiences are more likely to promote the transmission of underdog heroes than are courtly audiences.

Ziyad and the Arthurian tradition in Iberia

In order to understand how Ziyad relates to the chivalric romance in Iberia we need to know a bit about the reception of Arthurian romance on the Peninsula. When do Iberian authors begin to adapt literary representations of courtly behaviors such as are novelized in the Arthurian romances and the songs of the Troubadours? Our best-known examples are of course the Spanish chivalric novels of the sixteenth century, beginning with Montalvo’s Amadís de Gaula (1508), but there is significant evidence of Iberian reception Arthurian-style courtly discourse beginning in the twelfth century, when Iberian troubadours, writing in a variety of Peninsular literary languages, begin to make reference to Lancelot and Tristan in their verses (Entwistle 12; Thomas 22–23). By the first third of the fourteenth century, Peninsular readers have access to Castilian translations of the French narratives of the search for the Holy Grail. However, Ziyad is the first full-fledged work of narrative fiction in the Peninsula to present a chivalric world of such clear Arthurian influence, predating the Castilian translations of Arthurian texts nearly a century.

According to the fourteenth-century political theorist Ibn Khaldun, it is natural for nations who are dominated politically by their neighbor to imitate the cultural practices (including the literature) of the dominant kingdom:

a nation dominated by another, neighbouring nation will show a great deal of assimilation and imitation. At this time, this is the case in Spain [al-Andalus]. The Spaniards [Andalusis] are found to assimilate themselves to the Galician nations [Galicia, Asturias, Castile, Navarra) in their dress, their emblems, and most of their customs and conditions. (Ibn Khaldun 116)

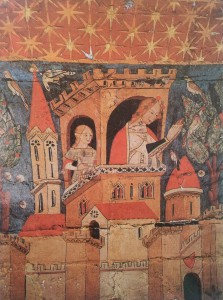

This idea is born out by other evidence in the plastic arts and to a lesser extent in literary sources. A brief overview of all other forms of commerce and exchange, including commerce, coinage, architectural styles, and eyewitness reports to the chivalric culture of Nasrid Granada demonstrate that the borders between Granada and Castile were culturally porous. Cynthia Robinson has described the thirteenth-century Granadan romance Hadith Bayad wa-Riyad as a kind of Andalusi roman idyllique (Robinson, Medieval Andalusian 172–182). Arthurian chivalric motifs even penetrated the Alhambra itself, as Cynthia Robinson demonstrates in her study of the ceilings of the Hall of Justice (Robinson, “Arthur”). This movement of Arthurian themes and chivalric sensibilities supports Ibn Khaldun’s assertion that the Granadans of his day were assimilated, to some extent, to the culture of the Christian North.

In Ziyad ibn ‘Amir al-Kinani we see a number of traits typical of the chivalric romance but less common in popular Arabic literary tradition. For example, there abound detailed descriptions of architecture and especially interiors, such as the castle of the princess Beautiful Archer where Sadé is being held captive:

I saw a castle whiter than a dove, whose high walls provided more shade than the clouds, built, for the most part, of carved plaster [like the Alhambra], stone, and carved wood. It was also built from rare bricks, crystals, and marble; it was surrounded by gardens planted with a variety of trees and at its highest point had three towers of fine sandalwood, where damsels, granted by God with beauty, grace, and happiness, played ouds and zithers. The wall of the palace was one hundred times the height of a man, and its diameter would have been eighty thousand arms’ length. (Fernández y González 13)

Medieval caricature of the Alexander-Porus battle (“Alexander defeats King Porus in single combat”(West Flanders; c. 1325-1335) (Source: 2nd Look)

Descriptions of knightly combat, such as the battle between the lord of al-Laualib castle and Sinan ben Malic, are also strikingly similar to those found in chivalric novels:

They attacked each other with lances until these broke, and then took to wounding each other with swords until these were dulled, then wrestled. They looked each other in the eyes, rubbed stirrups, and although their arms tired and their brows sweated, they continued to struggle for quite a long time. (Fernández y González 20)

In addition to these we can see in Ziyad something else characteristic of the Western chivalric romance: a consciousness and discourse of the chivalric code itself. The characters do not simply act according to the chivalric code, they discuss and reflect upon it. When Ziyad sneaks into the camp of Alchamuh and his daughter princess Beautiful Archer he reprimands Alchamuh to his daughter’s face: “I behaved correctly with him, freeing him from being struck by the lance in the presence of the Arab tribes [ie saving him face], and he repays me, in turn, robbing me of my wife in my absence, and capturing and killing my subjects and relations” (Fernández y González 12).

Conclusions

Ziyad and 101 Nights both attest to a corpus of Andalusi written popular literature giving voice to a specifically Iberian (or at least Maghrebi) experience vis-a-vis the Muslim East. This corpus is largely latent and we await quality Arabic editions and translations into other languages of Ziyad, the other 11 texts in Escorial Árabe MS 1876, the 101 Nights, and other texts as they come to light. Our findings are necessarily tentative, based as they are on translations, until such editions come to light. What we can state, however, is the following: Ziyad provides us with new, earlier examples of the penetration of Arthurian themes and motifs in the Iberian Peninsula that predate both the Castilian translations of the Arthurian romances.

Bibliography

- Auerbach, Erich. Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. Princeton: Princeton University, 1953. Print.

- Brownlee Scordilis, Marina. “Romance at the Crossroads: Medieval Spanish Paradigms and Cervantine Revisions.” The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Romance. Ed. Marina Scordilis Brownlee and Kevin Brownlee. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. 253–266. Print.

- Entwistle, William. The Arthurian Legend in the Literatures of the Spanish Peninsula. New York: Phaeton Press, 1975. Print.

- Fernández y González, Francisco, trans. Zeyyad ben Amir el de Quinena. Madrid: Museo Español de Antigüedades, 1882. Print.

- Fuchs, Barbara. Romance. New York: Routledge, 2004. Print.

- Heath, Peter. “Other Sīras and Popular Narratives.” Arabic Literature in the Post-Classical Period. Ed. Roger Allen and D.S. Richards. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008. 319–329. Print.

- Ibn Khaldun. The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History. Trans. Franz Rosenthal. London,: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1978. Print.

- Ott, Claudia. “Nachwort.” 101 Nacht. Zurich: Manesse Verlag, 2012. 241–263. Print.

- Robinson, Cynthia. “Arthur in the Alhambra? Narrative and Nasrid Courtly Self-Fashioning in The Hall Of Justice Ceiling Paintings.” Medieval Encounters 14.2 (2008): 164–198. Print.

- —. Medieval Andalusian Courtly Culture in the Mediterranean: Hadith Bayad Wa-Riyad. London: Routledge, 2007. Print.

- Sallis, Eva. Sheherazade through the Looking Glass: The Metamorphosis of the Thousand and One Nights. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon, 1999. Print.

- Segre, Cesare. “What Bakhtin Left Unsaid: The Case of the Medieval Romance.” Romance: Generic Transformation from Chrétien de Troyes to Cervantes. Ed. Kevin Brownlee and Marina Scordilis Brownlee. Hanover: University Press of New England, 1985. 23–46. Print.

- Thomas, Henry. Spanish and Portuguese Romances of Chivalry; the Revival of the Romance of Chivalry in the Spanish Peninsula, and Its Extension and Influence Abroad,. Cambridge: University Press, 1920. Print.

This post is based on talks at Yale University on April 23rd and 24th, 2015. Thanks very much to the Program in Medieval Studies and the Department of Spanish and Portuguese for their invitations.