This is the text of a guest lecture I delivered 28 October 2013 at NYU in Prof. Zvi Ben-Dor Benite’s class MAP-UA 500: Cultures & Contexts: Islam and Judaism: Intertwined Histories

Class reading: Maria Rosa Menocal, The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance, chap. 1-2, and pp. 101-129, 174-188.

Good morning Violets. It is great to be back in New York. Like you I went to college in Manhattan. I now live on the West Coast in an idyllic hippie university town which is very groovy and pleasant and interesting, but as you know there is really nothing like New York. So I thank Professor Ben-Dor Benite and the NYU Abu Dhabi Institute for their hospitality and for the opportunity to speak to you today. I hope that you will join me for my talk this evening at the NYU Abu Dhabi Institute at at 19 Washington Square North at 6pm.

Good morning Violets. It is great to be back in New York. Like you I went to college in Manhattan. I now live on the West Coast in an idyllic hippie university town which is very groovy and pleasant and interesting, but as you know there is really nothing like New York. So I thank Professor Ben-Dor Benite and the NYU Abu Dhabi Institute for their hospitality and for the opportunity to speak to you today. I hope that you will join me for my talk this evening at the NYU Abu Dhabi Institute at at 19 Washington Square North at 6pm.

In the fall of 1991 I got a job as a middle school ESL teacher at the Marta Valle Junior High School here in New York, on Rivington and Suffolk Streets. I had just graduated from Columbia with a degree in English. I had studied abroad in Spain and had enough credits in Spanish to qualify for emergency certification in Spanish with the NY Board of Ed. They put me in an ESL classroom. It was November 7th and I was the third hire of the academic year in that position, which gives you some idea as to the nature of the job. Probably about 85 percent of the students were Spanish speakers, Catholics, from the Dominican Republic, 10 percent were Bengali-speaking Muslims from Bangladesh. The faculty was split evenly between US Jews and Latinos. I had found, completely inadvertently, my own laboratory of convivencia, of coexistence between Muslims, Jews, and Christians.

This experience was a catalyst for my thinking about medieval Iberia. During my time in Spain I had become fascinated with Spain’s conflicted relationship with its Semitic cultural legacy. Here was a country that was perhaps the most Catholic country in Europe, historically speaking, and at the same time the most Semitic country in Europe. There was Arabic, Islamic, and Judaic culture all over the place – they just didn’t realize it, or care to admit it, it seemed to me at the time. This cultural tension fascinated me. Obviously Spain would never have become what it is without the contributions of Spanish Muslims and Jews, but the modern impulse to homogenize, to regularize, to whitewash history had its effect, and the result was a modern Spain with a lively substrate of Semitic cultural features just below the surface, and more often than not hiding in plain sight. I was mightily intrigued, but like many undergraduates I was more concerned with socializing, traveling, and entertaining myself than with charting a path for future study or embarking on anything resembling a serious career.

In contrast to Spain, in New York in 1991 there was no whitewashing or hiding. The convivencia was messy and in your face. There were regular misunderstandings between the students. Sometimes it was language: one Bangladeshi student, Shumon, was regularly called “Simón” by his classmates. They had conflicting ideas about how the world should work, about religion, about family, about a lot of things. Despite these very real differences, they were all united by the enterprise of learning English and by a school system and larger society that officially regarded them all as equals. Ricardo and Said and Rosalia and one polish kid named Slavomir sat next to each other in class, and more or less managed to get along, or at least not be in constant conflict, which for Middle School is probably as much as you can expect.

This experience, of seeing what convivencia really meant when the rubber hit the road, of what the daily negotiation of linguistic, religious, and ethnic difference looked like on the ground, stayed with me. Eventually I ended up back in graduate school with a mission to study this curious time and place, this culture that produced Ibn Hazm, Ibn Gabirol, Yehudah Halevi, and the other writers and thinkers who populate Menocal’s book as well as the readings for this week’s recitations.

After some experimentation, I landed in a Department of Spanish and Portuguese at Berkeley, where I finished the doctorate in 2003. I might well have completed the work in a department of Comparative Literature or Middle Eastern Studies, but what always seemed to unite the three religious cultures of al-Andalus, or of Christian Spain was the vernacular culture of the place. And this makes perfect sense. It is natural that people who live together, and work together have a common language. It’s logical. They might not pray together, they might not study together, and they may use different languages for those activities, but when they need to buy bread or rent a house or take care of business that has to happen in a common vernacular. This comes through very clearly in the study of the poetry of al-Andalus, especially in the muwashshahat and zajal genres of poetry that flourished in al-Andalus in the eleventh through thirteenth centuries.

Although I did not study with her, I was very much a student of María Rosa Menocal, whose book you have read for today’s assignment. Menocal, who just passed away last year, was a very important figure for those of us who study medieval Iberian culture, and in particular for those of us who specialize in the Hispano-Romance side of the equation but branch out as well into the Hebrew and Arabic materials. She was the one who made Hispanic Studies safe for Hebraists and Arabists.

There have been a number of popular trade books published on medieval Spanish topics in the last twenty years or so, but all of them were written by historians and focused on questions of historical interest, of the activities of kings, wars, and the like. Ornament was the first book written for a popular audience to focus on literature and music in its cultural context. It created quite a splash in the field when it was published. Many, especially historians, scoffed at the story she seemed to want to tell, decrying it as a squishy cumbaya, a rosy fanstasy of coexistence, despite the fact that she herself makes very clear in the introduction that this is not her intention; despite the fact that she deals very plainly with the problems of sectarian violence and discrimination in Ornament’s pages.

There have been a number of popular trade books published on medieval Spanish topics in the last twenty years or so, but all of them were written by historians and focused on questions of historical interest, of the activities of kings, wars, and the like. Ornament was the first book written for a popular audience to focus on literature and music in its cultural context. It created quite a splash in the field when it was published. Many, especially historians, scoffed at the story she seemed to want to tell, decrying it as a squishy cumbaya, a rosy fanstasy of coexistence, despite the fact that she herself makes very clear in the introduction that this is not her intention; despite the fact that she deals very plainly with the problems of sectarian violence and discrimination in Ornament’s pages.

This was not the first time Menocal raised the hackles of other experts in our field. Over almost thirty years ago she published a book called The Arabic Role in Medieval Literary History in which she challenged the prevailing theory of the origin of French troubadour poetry. Her theory, and really she was picking it up form earlier thinkers like Aloysius Nykl who had taught at Chicago in the 20s, was that troubadour lyric was inspired by Andalusi lyric.

On the face of things this is not outlandish –she basically just suggested that the poets of one country inspired poets in the next country to try composing in a new style. If I told you that American artists were composing Mexican-style corridos or were singing salsa in English this probably wouldn’t raise any eyebrows, but Menocal took on a kind of sacred cow in European literary history. Attributing Andalusi roots to the songs of the medieval troubadours was more like telling a Southern Aristocrat in the 1920s that their great-great-grandfather was from Africa. Menocal’s thesis struck at the roots of some very deeply held convictions about what “European” culture was and was not, and the idea that Andalusi, Arabic, perhaps African culture was somehow responsible for what had long been considered the first (and therefore the most authentic or most important) expression of poetry in the Romance languages was, well, unpopular. But like many ideas that go against received wisdom, Menocal’s thesis has gained wide acceptance. And not a moment too soon. Never have we been more in need of scholars and citizens eager to learn the lessons of the conviviencia laboratory. In the US as in Europe, violence against Arabs or quite often South Asians mistaken for Arabs, Jews, and Africans is on the rise. We need to start thinking about better ways to live with difference. Or, paraphrasing Menocal, if we want the world to become a “first-rate” place, we need to better learn how to live comfortably and productively with people of opposing viewpoints, who have different ways of doing things, of seeing the world.

Without dwelling too long on Menocal’s rich bibliography and interesting academic career, and before we go into the ideas she presents in the reading you’ve completed for today —you have completed it, right, I’d like to tell you something she said in a conference I attended in London about seven years ago, in her keynote speech to the assembled group of Hispanists, she implored us to spend our time on this globe and in this profession strategically. Paraphrasing Andy Warhol, she said: “when you finally get your fifteen minutes of fame, you better spend it saying something that matters.” This was an appeal for us to always keep in mind that our academic activities should be placed in the service of some higher purpose, of the social good, of trying to make the world a better place. While I had always suspected that under the layers of arcana, of dense footnotes, tweed jackets, and chunky jewelry, most academics’ intentions were good, I had never heard a professor say anything so forthright. These words stayed with me, and I would urge you all as well to think about them when you are studying Islamic history or Amazonian anthropology or Biochemistry — how can you take these skills and use them to make things better.

And now back to our regularly scheduled program. In Ornament of the World Menocal writes about a new kind of poetry, the muwashshah, invented by Andalusi poets. The innovation of the muwashshah was to take a popular tune, the type of tune you might sing while working around the house or while folding laundry – remember these are days before radio and mass media, so people had to entertain themselves instead of constantly tuning in. The poet would then take the melody of this popular tune, say Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines,” and build a literary, learned, classical poem on top of the tune and theme of the popular song. He would then set the poem to music, to a classical Andalusi orchestral setting, and the poem would be sung for the entertainment not of the ‘common people’ whose song provided the melody, but for the King, the élite, the upper crust of Andalusi society. This in itself was quite an innovation, the idea that popular music sung in the colloquial language might serve as the basis for a learned poetic composition worthy of performance before the king and the courtiers. These poems or muwashshahat were evidence of a very special kind of literary multiculturalism. No only did they combine the languages of the court and the street, they also were evidence of Arabic/Romance language bilingualism that was common in most of al-Andalus at the time.

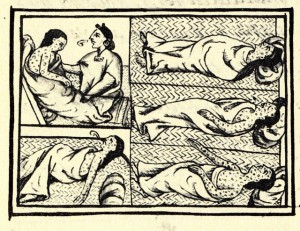

When the Muslim conquerors came in 711 and took hold of the Iberian Peninsula, the natives were a kind of mixture of Iberian, Celtic, Roman, and Gothic peoples who were speakers of Iberian vulgar Latin, the descendent of the spoken Latin of the Roman Empire. All of the Romance languages, Portuguese, French, Italian, and so forth, came from this language. The invasion was carried out by an army comprised mostly of newly Islamicized Berbers and an élite officer corps of Arabs from Syria and Yemen. It was not a highly Arabicized population —meaning that most of the troops did not speak let alone read Arabic— and we must remember that general literacy hovered somewhere between one and two percent in those days, compared with some 90 percent today in the US.

At the end of each muwashshah the poet included a snippet of the popular tune that gave the composition its melody. These snippets, or “exits” —kharjat in Arabic, were in colloquial language, either Andalusi Romance or Andalusi Arabic, further clear evidence of a bilingual society. We have other witnesses to this bilingualism. The very important Andalusi Jewish scholar Moses ben Maimon, better known as Maimonides, who was born in Cordoba, once wrote in a discussion of language that it was not uncommon for Jewish poets in Cordoba in the twelfth century to compose poems in Hebrew, or in Arabic, or in Andalusi Romance. The Hebrew poet Solomon ibn Gabirol once complained, in a long poem about Hebrew grammar, that half of the Jews of Zaragoza spoke “the language of the Christians” and the other half “Arabic” but that neither half had a proper command of Hebrew. Moshe ibn Ezra, who lived also in the eleventh century, wrote that when he was a young man he was in a discussion with a Muslim scholar who asked him to recite the Ten Commandments from the Hebrew Bible in Classical Arabic. Sensing that his interlocutor wanted to make his cherished biblical text sound silly in the “wrong” language, Ibn Ezra replied in kind, asking the young imam to recite the fatiha —the first chapter of the Qur’an, in Andalusi Romance, a language that, according to Ibn Ezra, the imam understood very well. Linguists writing in Arabic in the tenth and eleventh century likewise document several varieties of Romance spoken in different areas of the Peninsula. Romance speakers did not simply dry up and blow away with the Islamization and Arabization of the Peninsula, but rather adapted to the new circumstances, as people tend to do.

We should also remember that the Arabization of the peninsula was, like the Hispanicization of the New World, slow and incomplete. Many of the Berber troops who accompanied the Arabic officers in the first invasion partnered with local women who were Romance speakers, whose children would have been bi- or tri-lingual in Romance and Arabic and/or Berber. By the middle of the eleventh century it is thought that over 80% of Andalusi Muslims were descended from Iberians who had converted to Islam from Christianity and we must imagine that even by the third or fourth generation since the invasion the Arabization of the local populations would have been far from total, particularly in rural areas where people were not in close contact with Arabic-speaking government officials and functionaries. So we can conclude that when an eleventh-century Andalusi poet includes a bit of colloquial Romance in a poem, it is not some exploitation of the language of a Christian minority, but rather a representation of a more generalized bilingualism among all religious groups in the Peninsula.

Regardless of the language one spoke at home in al-Andalus, Andalusi Romance, Andalusi Arabic, Berber, or some combination of the three, the official language of prestige, of the court, of the high culture of the day was classical Arabic. As you have learned, this was not a language exclusive to Andalusi Muslims. The docrtrine of dhimma meant that Christians and Jews were well able to participate in public life, and in rare cases like that of Hasdai ibn Shaprut at the court of Abd ar-Rahman in the tenth century and Samuel Hanagid Naghrela at the court of Badis in Granada in the eleventh, could rise to very high positions. Part of the success of these courtiers was their mastery of the classical Arabic language and its poetic and literary tradition. In the same way that nowadays one can go higher in business or public administration, or education with an advanced degree, mastery of formal Arabic and of the scholarship, poetry, and courtly literature in Arabic was the key to advancement. The ability to write an eloquent letter in rhyming prose or to be able to extemporize in verse on any subject was the mark of an adib, a literato, and one of the core competencies of high level government officials.

It should hardly come as a surprise, then, that such men would think to imitate this style of Arabic poetry in their own liturgical language in Hebrew. After all, if they were important enough to help run the government and the army, their literary tradition should reflect this level of prestige, and the way to do so was to write in Hebrew as if it were Arabic. What did this mean? Was there no poetic tradition in Hebrew? Why this wholesale adoption of Arabic poetics?

There was a tradition of liturgical poetry in Hebrew, but it was increasingly irrelevant to the poetic tastes of the day. Arabic poetry, with its long legacy that predated Islam, had a vast repertoire of desert-based imagery and rhetorical figures, of clichés that poets recast and reinvented constantly, always making references, whether reverent or ironic, or downright parodical, of poets of past generations. It was a long, very complex, and very serious game, if you will. Translating this game into Hebrew was a natural extension of the literary culture in which they moved.

What they did not have at their disposal was a tradition of profane, or non-religious poetry. The topics, the imagery, the clichés, the poetic vocabulary of love, war, praise of great deeds and ridicule of the rival, all of these poetic conceits they borrowed from the Arabic tradition. The language they used to do this was the Hebrew of the Bible. The result was a kind of mosaic by which they used words and whole phrases lifted directly out of the Hebrew Bible to give voice to images and metaphors drawn from Arabic tradition. One way to look at this is that it became a kind of contest between Hebrew and Arabic to see which was the most vibrant, most authoritative language. If Arabic poetry drew some of its cultural authority for being written in the language of the Qur’an, then Hebrew poetry drew its authority from the Tanakh or Hebrew Bible. Eventually Hebrew poets began to give voice to this rivalry in debate poems and essays that touted Hebrew’s superiority over Arabic, much as Arab poets had once written on Arabic’s superiority over other languages spoken by non-Arab Muslims such as Persians. This discourse has its beginning in the eleventh century, when Moses ibn Ezra explains that Hebrew takes Arabic as its model:

And the poetry of Moses was true and kingly,

Like an Arabic poem, in words of sweetness.

And one speaking in the language of the Jews,

Spoken in perfect symmetry,

And the power of the speech of Araby

With its turns of phrase and eloquence.

Delightful sayings, in the Arabic tongue or the Hebrew,

And wisdom to grasp on every side, from each direction.

(Allony 35)

Over time Hebrew poets became more militant, almost nationalist in their arguments, so that by the beginning of the twelfth century, when Arabic was on the decline as a literary language in the parts of al-Andalus, such as Toledo, that had since been conquered by Christians, poets now championed Hebrew as superior to Arabic. Judah al-Harizi, a writer from Toledo who lived in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, wrote the following:

They have enslaved the tongue of the Israelites to the tongue of Kedar [i.e., Arabic] and they said: ‘come let us sell her to the Ishmaelites.’ And they said to her: ‘Bow down, that we may go over.’ And they took her and cast her into the pit until she perished among them. And the tongue of Kedar blackened her, and like a lion, tore her. An evil beast devoured her. All of them spurned the Hebrew tongue and made love to the tongue of Hagar. (al-Harizi 32)

The irony is that these proclamations of the superiority of Hebrew, which were probably more like literary exercises than serious manifestos of linguistic policy, were couched in a register of Hebrew that owed everything except for the words themselves to Arabic. As I said earlier, these compositions were like mosaics in which the poets constructed the images and poetric conceits of Arabic using tiles cut from the Hebrew Bible. Later writers used the metaphor shibbutz to describe this style, meaning inlay, just as a precious gem set in a gold setting is made from a different material but forms a part of the overall composition of the piece.

I’ll give you an example from a muwashshah by Abraham ibn Ezra (no relation, as far as we know, to Moses ibn Ezra) who wrote in the twelfth century. The bold text shows the direct quote from the Biblical Hebrew. The final couplet in italics is a kharja in colloquial Andalusi Arabic, which contrasts sharply with the Biblical Hebrew of the rest of the composition:

The choice honey from your lips is sweet;

It is God’s work, unblemished.

Your breath smells like apples.

My beloved, where have you eaten the apple?

Come and say to me: ‘Ahhhh’

(Ibn Ezra 90)

This is a direct quote from the Biblical Shir ha-Shirim, or Song of Songs, also known as the Song of Solomon, where the lover describes his beloved. In the literal sense of the Biblical text, the poetic voice describes the body of the beloved in a series of agricultural metaphors that suggest fertility and echo the idyllic setting of the love encounter.

I said: ‘I will climb up into the palm-tree,

I will take hold of the branches;

And your breasts are as clusters of grapes,

Your breath smells like apples (Song of Songs 7:9)

The effect is a kind of layering, an ironic juxtaposition of the original Biblical context and the Andalusi Hebrew poetry and adaptation of Arabic poetics. The poets deployed the ancient biblical language in a poetic setting that was purely Andalusi and contemporary and, it should be stressed, not always devotional or pious. Of course one might argue that the Song of Songs itself is not a particularly pious text as far as the Biblical canon goes. Later interpreters of the song read it as an allegory for the relationship between the Jewish people and God, but it was originally probably just a very successful love poem at the court of Solomon or David, not unlike an Andalusi qasida or ode, with an amorous theme, that for its popularity came to be included in the biblical canon and pressed into service as a devotional allegory.

In Menocal’s controversial thesis about the origins of troubadour poetry she proposes that this style of Andalusi lyric poetry made its way north across the Pyrenees and served as the inspiration for the first courtly lyric poetry in the Romance languages, and by extension the first “literature” in the Romance languages.

The story is pretty straightforward. In 1064 Sancho Ramírez of Aragon enlisted the help of a number of foreign noblemen from north of the Pyrenees in the siege of Barbastro, which then belonged to al-Muzaffar, the King of Lleida, now part of Catalonia. The campaign was preached by Pope Alexander II as a kind of proto-crusade, for the First Crusade to the East was not launched until 1096. Since the 1060s the Vatican had run a series of test campaigns in Spain. Popes issued bulls, or official documents that guaranteed remission of sins to all those who participated in sanctioned military actions against non-Christian enemies. So in a way, Spain was a kind of a test ground for the Crusades, and Barbastro was an important one of these trial runs.

The story is pretty straightforward. In 1064 Sancho Ramírez of Aragon enlisted the help of a number of foreign noblemen from north of the Pyrenees in the siege of Barbastro, which then belonged to al-Muzaffar, the King of Lleida, now part of Catalonia. The campaign was preached by Pope Alexander II as a kind of proto-crusade, for the First Crusade to the East was not launched until 1096. Since the 1060s the Vatican had run a series of test campaigns in Spain. Popes issued bulls, or official documents that guaranteed remission of sins to all those who participated in sanctioned military actions against non-Christian enemies. So in a way, Spain was a kind of a test ground for the Crusades, and Barbastro was an important one of these trial runs.

With the aid of the Popes, Christian Iberian rulers could count on reinforcement troops who came to their aid not only for the promise of booty or future reciprocation, but also for spiritual gain and for expedited access to heaven. However, there was nothing wrong with learning some new songs along the way, apparently, for William the eighth of Acquitaine, who provided the largest contingent of foreign troops in the campaign, received as part of the spoils a troop Andalusi qiyan, women educated in the poetic and musical styles of the court. These qiyan were more like music professors than slaves forced to sing in a choir. They brought with them to Acquitaine the instruments, music theory, techniques, and reptertoire of the Andalusi musical and poetic traditions. Each of them had memorized thousands of compositions of Andalusi poets. This amounted to an “Andalusi” invasion in the music scene of Southern France. As Menocal points out, the young William the Ninth of Acquitaine grew up with these Andalusi qiyan as the house band, or the court musicians of his father William the Eighth of Acquitaine. Young William IX was the man who would become known as the first troubadour, the first artist to compose and perform courtly lyric verse in the vernacular as opposed to Latin. This was a big deal – just as big a deal as when the first Andalusi poets started singing songs in vernacular Arabic and Romance at court in the tenth century.

So why was this thesis so controversial? Some literary critics had since the nineteenth century suggested that Troubadour poetry has its origins at least partly in the courtly traditions of al-Andalus, which was offensive to those who held the idea of a “pure” French literary tradition close to their hearts. And we must remember, the nineteenth century was the time when most of our ideas about nationhood and nationalism were formed. This was time time of great linguistic homogenization, when public schools began to teach a national language, a national culture, a national ethos. This is the time of various pseudo-scientific approaches to ethnic identity, of phrenology, of theories of biological ethnic identity the type of which eventually gave us Nazi Aryanism. One’s national language was an essential part of one’s sense of national identity, an identity that was said to be carried in the blood, an identity that was biological fact. In this environment, to suggest that the foundational forms of French poetic tradition were an import from Spain, and ultimately from Africa, was nothing less than an affront to national honor.

But it gets worse. In 1948 a researcher named Samuel Stern made a remarkable discovery. He was examining some manuscripts of Andalusi Hebrew muwashshahat such as those we have seen and came across some very cryptic verses of which he could not get a clean reading either in Hebrew or in Arabic, meaning that the letters did not appear to add up to words that made sense either in Hebrew or in Arabic.

Stern was trained in both Semitic and Romance languages and he eventually put it together that these verses were written in Hebrew characters but that the language they represented was not Hebrew, not Classical Arabic or colloquial Andalusi Arabic, but another language entirely —Andalusi Romance, the dialect of Romance spoken in al-Andalus:

Des kand meu Cidello benid

ton bona al-bishaara

com ray de shol yeshed

fi waad al-hijaaraWhen my Cidello arrives,

What glad tidings!

Like a ray of sun he comes out

in Guadalajara

This meant that the first courtly poetry written in a Romance language was not the French troubadour poetry, but the, well what was it exactly? The popular Andalusi ditties remixed by classical Arabic and Hebrew poets? The sound bites of popular tunes preserved in longer, learned compositions?

Whatever you chose to call it, it meant that Spain, in 1948, could now (if they chose to, which is another matter entirely) boast the first written lyric of Romance tradition! Spain, which had been invaded by Napolean, Spain which had always, in the European context, been the African red-headed stepchild south of the Pyrenees. Spain, which even had its own term for someone who regarded French culture as more prestigious than one’s own: “afrancesado,” roughly “frenchified.” Yes, Spain was now the bearer of the first, the original, the most authentic, the oldest something in Europe.

But there was still that annoying detail of the Hebrew and Arabic poetry that allowed Romance poetry to enter the literary arena. Hmm. In an age of pure literary histories this was problematic. But luckily there was a simple solution. The kharjat could simply be studied as a case of Romance resistance to Semitic hegemony, the Romance flower pushing up through the Semitic pavement, evidence of the creative spirit not of the innovative Arabic and Hebrew poets who incorporated the popular Romance ditties, but of the indomitable spirit of the Latin people whose poetic ingenuity shone through and entranced even their swarthy, foreign oppressors.

For the Spanish critic concerned with maintaining the integrity of Spanish as a national language, the Romance kharjat of the Andalusi muwashshahat were evidence both of the enduring Hispanic spirit, as well as the primacy of Hispano-Romance over Franco-Romance in written lyric tradition. Eventually, editors of textbooks sidestepped the issue entirely, rendering cleaned up, de-Arabicized versions of the kharjat (rendered jarchas in Spanish), in total isolation from the Arabic and Hebrew muwashshahat of which they formed an integral part. Nearly every textbook of Spanish literature includes the Romance kharjat as the first example of Spanish literature, but not a single one includes the Hebrew and Arbabic poems from which the kharjat are mined. It is as if the Hebrew and Arabic compositions were a seed case providing nutrition to the kernel of the kharjat, keeping it alive until the day that it might sprout in the fertile black earth of modern European nationalism.

For the Spanish critic concerned with maintaining the integrity of Spanish as a national language, the Romance kharjat of the Andalusi muwashshahat were evidence both of the enduring Hispanic spirit, as well as the primacy of Hispano-Romance over Franco-Romance in written lyric tradition. Eventually, editors of textbooks sidestepped the issue entirely, rendering cleaned up, de-Arabicized versions of the kharjat (rendered jarchas in Spanish), in total isolation from the Arabic and Hebrew muwashshahat of which they formed an integral part. Nearly every textbook of Spanish literature includes the Romance kharjat as the first example of Spanish literature, but not a single one includes the Hebrew and Arbabic poems from which the kharjat are mined. It is as if the Hebrew and Arabic compositions were a seed case providing nutrition to the kernel of the kharjat, keeping it alive until the day that it might sprout in the fertile black earth of modern European nationalism.

This tension between Spain’s Christian European identity and historic Muslim, Arab, and Jewish legacies has a very long history. Menocal writes at length on the journey of the Cluniac Abbot Peter the Venerable to Spain in order to produce a reliable Latin translation of the Qur’an. This trip, which Peter undertook in the middle of the twelfth century, at the height of the crusading movement both in the Peninsula and in the Eastern Mediterranean, had another purpose. The Cluniacs, a French-based religious order, were carving out new territory south of the Pyrenees. The establishment of Cluniac monasteries, and in particular the appointment of Cluniac and other non-Hispanic churchmen to highly placed positions in the Spanish church was part of a program to minimize the influence of Mozarabic Christians in the Spanish church.

As you have read, Christianity thrived in al-Andalus during the centuries of Muslim political dominance, and Hispanic Christians over time had developed their own rite and liturgy, which came to known as the Mozarabic rite. “Mozarab” is a word derived from the Arabic musta’rib, or one-who-has-become-arabized. It was used to refer to the Hispanic Christians who has become acculturated to the dominant culture of al-Andalus, adopting Andalusi Arabic as their spoken and Classical Arabic as their written languages. These Andalusi Christians were viewed as somewhat problematic by the Church hierarchy, once the north of the Iberian peninsula was reincorporated into Western Christendom. They were too, different, too Arabic, and the Vatican encouraged efforts to minimize their influence in the Church in Christian Iberia. This was a difficult proposal. In Toledo, a city of great commercial, spiritual, and political importance, and the former capital of Visigothic Christian Spain, the Mozarabic elites dominated the Church.

In the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, Western Christendom was on the move. With the enthusiastic approval of the Popes, Western knights had run several campaigns of crusade in Jerusalem, Syria, and even came to topple Christian Constantinople and install their own French Byzantine Emperor in place of the Greek, Christian Emperor there. By this time the tentative project of Crusade in Iberia had become a full blown holy war, and by the middle of the twelfth century Christian kings such as Jaume the First of Aragon spoke of their military struggle against al-Andalus in terms of Holy War, and making no bones about it.

In this context, the Mozarabic church and the Andalusi culture it represented looked a little bit too much like the enemy, and the same Popes who declared Byzantine Greek Christians to be heretics —and therefore totally legitimate military targets— turned their sights on the Mozarabic church elite in Spain. We should remember that two of the most important Christian kings in Spain during the thirteenth century were made saints for their military exploits against Islam. Louis IX, who nearly bankrupted his royal treasury financing a failed crusade and buying relics stolen from the Byzantine church by the crusaders, was sainted only two years after his death. Fernando III of Castile-Leon, who conquered Seville and Cordoba, at the time the two most populous and sophisticated cities in the Iberian peninsula, had to wait until the seventeenth century for sainthood but was revered as a holy warrior during his own lifetime.

By the mid-fourteenth century the Mozarab elites of Toledo were effectively acculturated, and their use of Arabic was limited to the most formulaic of legal documents. The population had probably been fully hispanized by the close of the thirteenth century in any event. Though large number of Muslims remained in Christian kingdoms until well into the sixteenth century, outside of the tributary kingdom of Granada Arabic as a literary language has more or less breathed its last by the close of the fourteenth century. As you well know, after sending Columbus westward Isabel and Ferdinand expelled the Jews from their kingdoms, and over a century later Philip the second would do the same with the descendants of the Andalusi Muslims who had been forcibly converted in the beginning of the sixteenth century.

Yet try as they might, Christian Iberians were never able to reconcile itself to its Semitic heritage. Some, like the Spanish novelist Juan Goytisolo, argue that this cultural closing would be the most significant factor in Spain’s economic and intellectual backwardness in the European context, and that only now in the age of official multiculturalism ushered in by the policies of the European Union can Spain come forward to claim its rightful role as the historical multicultural example for neighbor countries such as France and Italy who are struggling to articulate national cultures that are open to European Islam, to European Africanness and other forms of cultural difference. Scholars like Menocal have striven to interpret the past in ways that can be productive for the future, to find even in conflictive moments the pearls of cultural exchange and collaboration, of shared enterprise and shared values. These are the examples that can inspire policy and practice, that actually can affect the way we govern and are governed, and the way we live our lives every day.

Works cited

- al-Harizi, Judah. The Takhkemoni. Trans. Victor Reichert. Jerusalem: Raphael Haim Cohen, 1965. Print.

- Ibn Ezra, Abraham ben Meïr. Twilight of a Golden Age: Selected Poems of Abraham Ibn Ezra. Trans. Leon Weinberger. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1997. Print.

- Menocal, María Rosa. The Ornament of the World. Boston: Little Brown, 2002. Print.