Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Eden in the Alba Bible (15th c.)

Medieval Iberians of all three religions participated in a common culture of retellings of material from the Hebrew Bible that fused the doctrines of Islam, Judaism, and Christianity with the vernacular languages and cultures common to all three groups. This shared storyworlding is expressed in a body of texts that includes versifications, chronicles, translations, art, and exegesis. Here I will discuss how the use of a vernacular common to all three religious groups shapes the creation of a shared storyworld that brings together Jewish, Muslim, and Christian audiences, at times through Biblical traditions, languages, and vernacular culture.

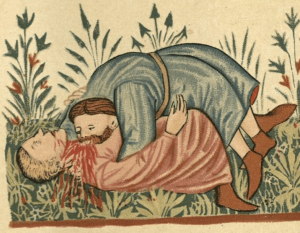

Cain bites Abel on neck, Alba Bible (15th c.)

It makes sense that vernacular retellings of the Hebrew Bible, as opposed to those written in classical languages of a given religious group (Hebrew, Classical Arabic, Latin) were the most accessible to members of all three groups who shared a common language. This is not true in every circumstance, however. Not all Granadan Muslims, for example, were speakers of Castilian in the year 1300 (when Andalusi Arabic was still dominant), and so would not comprehend retellings in Castilian. Most Jews were not likely to hear Castilian or Catalan Biblical tales in sermons by Christian priests except when they were mandated to attend sermons preached by Dominicans and Franciscans. However, there are many retellings that are linguistically, culturally, and situationally accessible across groups, and this access makes it possible for these groups to develop a shared understanding of the storyworld of the Hebrew Bible.

Storyworld Create a Story Kit (source: https://www.candlewick.com/)

What is a storyworld? The idea of storyworld grows from the reader reception theory of the 1970s and 80s in which the object of study is not only the text, but rather extends to the experience of the audience as part of the constitution of the literary work. That is, the text is only one part of the work. We can think of the storyworld as a collaboration between text and audience. This approach is useful for studying the interactions between different religious traditions, because the focus on audience experience helps us conceptualize the continuity of experience between texts and audiences representing distinct religious traditions but shared literary experiences.

One of the earlier theorists of the storyworld, Seymour Chatman, posited the binary of discourse and story, in which the discourse refers to the text, and the story is “the continuum of events presupposing the total set of all conceivable details actually inferred by a reader [audience]” (Chatman 28; Thatcher 28). For the narratologist David Herman, storyworlds are simply “the worlds evoked by narratives” (Herman 143). María Ángeles Martínez builds on these ideas, adding that “storyworlds are mental models of situations and states of affairs which are linguistically or multimodally prompted by narrative discourse” (Martínez 28).

What does a storyworld do? How is it a useful tool for reading retellings of the Hebrew Bible? Scholars of contemporary media use it as a construct to study audience interaction with coherent multi-platform or ‘transmedial’ narrative worlds (Ryan), such as Star Wars narratives that proliferate across film, novels, graphic novels, and videogames.

Lego Star Wars video game (source: https://starwars.fandom.com/)

The Bible already does this by lending coherence to its many books (‘Biblia’ is the Greek plural for ‘book’) and the multiple, sometimes contradictory traditions on which it draws. The canonical and apocryphal books of the Hebrew Bible texts are the base, and the various retellings in theater, legend, chronicle, and verse expand and innovate. Storyworlds provide us with a conceptual frame to organize and provide coherence for our readings of the individual texts, and a lens through which to view questions of how narrative works.

I’ll give a few examples to show three different ways in which this happens in the texts: (1) the expression of emotional states, (2) the description of shared material culture, and (3) the use of genres, tropes, and forms common to vernacular narrative genres across religious traditions.

The Binding of Isaac, in Les anciennes hystoires rommaines, MS Royal 16 G VII, f. 28, 14th c. British Library (source: thetorah.com)

One story very familiar to all three groups is the story of the aqedah or binding of Isaac (Ishmael in Islamic tradition) told in Genesis 22. We know the story: God commands Abraham to offer Isaac as a sacrifice. Abraham complies, and just as he is about to bring the knife down on Isaac’s throat, God sends an angel to stop him, telling him that he has passed God’s test.The 15th-century Valencian biblical play Sacrifiçi de Isaac (Sacrifice of Isaac) takes some dramatic liberties with this scene, taking it in a more burlesque direction, and adding more affective detail in the representation of both the Angel and Abraham, couched in familiar vernacular tropes of badgering and annoyance:

Angel [in the voice of an old lady]: Abraham! Abraham!

Abraham: What do you want, sir?

L’Àngel, a to de ‘Vexilla.’: “Habram! Abram!”

Habram: “Què vols, senyor?” (Huerta Viñas 128)

The voice of the Angel is cast in the misogynist trope of the meddling older lady, and Abraham’s response is not the obedient “here I am” of the bible, but rather què vols? the Valencian equivalent of “whattaya want, already” of the stereotyped man chafing at a female questioning his actions. I argue that it would be far more difficult to communicate these affective states in Biblical Hebrew or Latin, and that it is the vernacular medium that opens the traditional text to this affective texturing of the story, a vernacular experience that is shared by Jews, Christian, and Muslims in the street watching the drama.

antique hetchel for processing wool or flax (18th c.?) (source: pinterest.com)

Elsewhere authors of biblical retellings use material culture as a reference point in describing things that might be unfamiliar to audiences. The 13th-century Castilian General estoria, compiled under the direction of Alfonso X of Castile, in an excursus in the Joseph story on the Nile river adapted from Pliny, describes the crocodile (cocodriz): The compilers write that

on both jaws are many strong teeth, that are fashioned and positioned just like they are on the iron combs used to process wool.

en amoz los carrirellos á muchos dientes e muy Fuertes, e tiénenlos assí texidos e puestos eguales como están los dientes en los peines de fierro que lavran la lana. (Alfonso X I:8, xiv, 435-436)

Here the compilers draw on the vernacular material culture, one shared across religious groups, to help audiences perhaps not personally familiar with crocodiles to populate parts the Joseph storyworld.

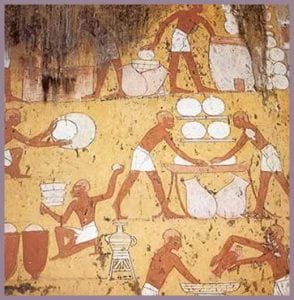

And Jacob saw there was grain in Egypt

Senet’s Tomb (TT60), Luxor, Egypt, 20th c BCE (source: https://stravaganzastravaganza.blogspot.com/)

Our sources also share folkoric tropes and motifs drawn from the vernacular culture shared by Muslims, Jews, and Christians. The retelling of the Joseph story in the fourteenth-century Coplas de Yosef, a Hebrew aljamiado versification in mester de clerecía tells of how Jacob learns about the stores of grain in Egypt during the famine in his homeland of Canaan:

Jacob, there in that land where he dwelled [Canaan],

Went to the river and looked at the water:

He saw a lot of straw floating along in the river,

The same straw that Joseph had spilled [upriver in Egypt].

Ya’aqob en esa tierra, allá donde estaba,

al río se fuera y las aguas miraba:

mucha paja viera que en el río andaba,

esta paja fuera que derramó Yosef.

(Girón-Negrón and Minervini 141, st. 76).

While Genesis 42:1 relates only that Jacob “saw there was grain in Egypt” (וַיַּ֣רְא יַעֲקֹ֔ב כִּ֥י יֶשׁ־שֶׁ֖בֶר בְּמִצְרָ֑יִם), Rabbinic sources provide various explanations: Jacob saw it in a vision (Bereshit Rabbah); Jacob lost his prophetic vision after Joseph was sold and only saw the ‘hope’ of bread in Egypt (Rashi); Jacob literally saw men with wheat and asked them, then understood that they had bought it in Egypt (David Qimhi). None of these account for the novel solution of the Coplas de Yosef, but the editors of the Coplas, Laura Minervini and Luis Girón-Negrón, locate the motif in a folktale collected in Burgos, Las señas de la batalla:

They threw the straw in the river for them to see the sign of what they were going to do. When the river water with the staw reached them, they knew that they had won the battle.

Les echaron al río [las pajas] para ver la señal de lo que iban a hacer. Cuando llegaba el agua del río con las pajas es que habían ganao la batalla. (Pedrosa 95; Girón-Negrón and Minervini 249 n 74–78)

This motif is adapted in the Coplas as a novel interpretation of Genesis under the influence of regional vernacular culture shared across religious communities, and its use in building out the storyworld of the Joseph narrative connects Jewish, Muslim, and Christian speakers of Castilian familiar with it from oral tradition [I have written about the transmission of narrative across religious groups via oral tradition here and here].

Hopefully these few examples begin to paint for you the picture of a community of Biblical interpretation at once divided by religious tradition and bound together by common vernacular language and culture, one that facilitated the practice of a shared Biblical storyworld. Stay tuned for more in future posts on this topic!

Works cited

- Chatman, Seymour Benjamin. Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film. Cornell University Press, 1978.

- Girón-Negrón, Luis M., and Laura Minervini. Las Coplas de Yosef: Entre La Biblia y El Midrash En La Poesía Judeoespañola. Gredos, 2006.

- Herman, David. Narrative Theory: Core Concepts and Critical Debates. Ohio State University Press, 2012.

- Huerta Viñas, Ferran. Teatre Bíblic: Antic Testament. Editorial Barcino, 1976.

- Martínez, María-Ángeles. Storyworld Possible Selves. De Gruyter, Inc., 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uoregon/detail.action?docID=5156565.

- Pedrosa, José Manuel. Héroes, santos, moros y brujas : Leyendas épicas, históricas y mágicas de la tradición oral de Burgos : Poética, comparatismo y etnotextos. Elías Rubio Marcos, 2001.

- Ryan, Marie-Laure. “Transmedial Storytelling and Transfictionality.” Poetics Today, vol. 34, no. 3, Sept. 2013, pp. 361–88.

- Thatcher, Tom. “Anatomies of the Fourth Gospel: Past, Present, and Future Probes.” Anatomies of Narrative Criticism: The Past, Present, and Futures of the Fourth Gospel as Literature, edited by Tom Thatcher and Stephen D. Moore, Brill, 2008, pp. 1–35.

- Ukas, Catherine Vool Rytell. The Biblia Rimada de Sevilla: A Critical Edition. University of Toronto, 1981.

This post is a version of a paper given at the 2022 MLA Convention, in the panel “New Currents in Medieval Iberian Studies” organized by the Medieval Iberian LLC Forum and presided by Robin Bower.