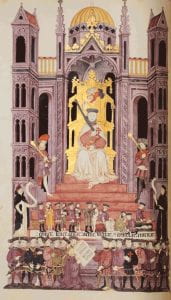

Rabbi Moses Arragel presents Arragel Bible to Don Luis de Guzmán, Biblia de Alba (f25v). Source: facsimile-editions.com

1420: Rabbi Moshe Arragel of Guadalajara was in a quandry. The powerful Luis de Guzmán, a high-ranking nobleman and Master of the influential Order of Calatrava invited him (and this was an invitation that the Rabbi could not refuse) to collaborate on a ground-breaking translation of the Hebrew Bible into Castilian, with an accompanying commentary interpreting both Jewish and Christian exegetic traditions. He was to work under the supervision of a Catholic priest, a Franciscan Friar who would represent the Christian interpretations, but Guzmán assured Arragel that he would have freedom to represent both traditions, provided that he gave no offense to Christianity.

This project was unique for its time (insofar as we know from the documentary record that has survived). Iberian Rabbis did not typically work in Castilian. When they did, such as the case of Rabbi Shem Tov ben Isaac Ardutiel of Carrión (known in Spanish as Shem Tov or Santób de Carrión), it was at the behest of a powerful Christian noble or king. Unlike Arragel’s translation and commentary, Ardutiel’s Proverbios morales (ca. 1330) were not meant to be a true representation of Jewish tradition, nor did he cite Jewish sources, or enter into the details of Rabbinic interpretations of Biblical texts that were by nature polemical in that they differed and at times contradicted Christian interpretations. Arragel was breaking new ground with this project.

The work is fascinating on a few levels. The glosses are a treasure trove of late medieval intellectual, rabbinical, and theological material. Arragel brings a considerable background in Rabbinics, science, and general knowledge to the project. Scholars have written excellent studies on its linguistic characteristics, its illuminations, and to a certain extent, its treatment of Jewish and Christian traditions. What I find most fascinating is Arragel’s engagement with the vernacular culture of his day: turns of phrase and colloquialisms, his use of popular verbal and literary genres such as proverbs and exempla, his tendency to explain Biblical society in terms familiar to his 15th-century audience, and his innovation in recasting rabbinic concepts and arguments in vernacular Castilian. Arragel’s Bible is the richest repository of the Iberian Jewish vernacular for the pre-expulsion period, hands down. Here I will give a few examples of his innovative use of colloquialisms, proverbs, exempla. I’ll explain how he translates the world of the Bible and the Rabbis for his 15th century Castilian readers, and make some suggestions to what is at stake, culturally and intellectually, in his doing so.

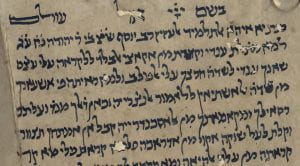

Page from manscript of Maimonides’ Guide for the Perplexed (Yemen, 13th-14th c.) Source: wikipedia.org

Hebrew was not in any sense a vernacular language for Iberian Jews and had not been a vernacular language since the days of King David (ca. 1000 BCE). It was a language of learning, and, like Latin for learned Christians, sometimes pressed into service as a lingua franca between Jews whose vernaculars were mutually unintelligible. When Jews wrote in Hebrew, they did not have access to the expressive repertory of the vernacular. We know, for example, that Iberian Rabbis gave sermons in the vernacular, but recorded them in Hebrew. We have a few examples of medieval Jewish verse in the vernacular, such as the versification of the Joseph story (Coplas de Yosef), or the Proverbios morales of Rabbi Shem Tov Ardutiel we mentioned above. As I have written elsewhere, these contain some very interesting examples of how Jewish writers blend vernacular Castilian and religiously Jewish textual sensibilities. But Arragel’s work shows us just how deep this particular rabbit hole goes. He is perfectly at home in the vernacular, and, like Ardutiel, free to mine the full range of vernacular rhetorical resources for his purposes as a Biblical commentator. This brings the stories and arguments alive for Castilian readers in ways that are simply impossible in Hebrew, which could not resonate in the same way for Castilian speakers.

Public shaming in stockade (with eggs) Coutumes de Toulouse (1295) BNF Latin 9187 f.30v Source: gallica.bnf.fr

In his commentary on the Joseph story, he renders an argument by Rashi into colloquial Castilian. Rashi makes the point that “Esto asy Joseph fizo porque se non auergonçasen sus hermanos en plaça”” (Gen 45 :1) (Paz y Meliá, Biblia de Alba: Genesis 156) Rashi: “He could not bear that the Egyptians should stand by him witnessing how his brothers would be put to shame when he made himself known to them.” For Castilian speakers, the phrase “Avengonzarse en plaza” (‘being shamed in plaza,’ i.e., in public) is close to their lived experience; they have been ‘shamed in the plaza,’ and have heard people speak in exactly those terms. They have embodied experience linked to this language in ways that they do not with the Hebrew term Rashi uses, מִתְבַּיְּשִׁין (mitbayyeshín). And this is only considering Arragel’s Jewish audience. His Christian audience, save for a very few learned clerics or converts from Judaism, would have had very limited access to the commentaries of the Rabbis. While it is true that Christian clerics read Latin commentaries, such as the highly influential Postillae of Nicholas of Lyra, that drew on Rabbinical sources, Arragel’s commentary brought the Rabbis to life for readers of Castilian in ways that must have greatly expanded their notion of Rabbinical discourse, and of Jewish tradition in general.

A medieval depiction of a feast; Speculum humanae salvationis, London, 1485-1509; British Library, Harley MS 2838, f.45r. Source: www.bl.uk/

The story of Jacob’s vision of angels moving down and up a celestial staircase or ladder is well known. On his way from Beersheva to Haran, he beds down in the wilderness, using a stone for a pillow:

He came upon a certain place and stopped there for the night, for the sun had set. Taking one of the stones of that place, he put it under his head and lay down in that place. (Gen 28:11)

The rabbis have a lot to say about this pillow (as they do about most things). Arragel’s characterization of the Talmudic Rabbis’ tendency toward over-interpretation is clear in how Arragel summarizes Talmudic interpretations of Jacob using a stone for a pillow:

E tomo de las piedras del lugar e puso a su cabeçera: Deste dezir fazen los talmudistas grande fiesta, e non lo judgan al pie de la letra… (Paz y Meliá, Biblia de Alba: Genesis 140)

And he took a stone from the area and put it under his head: The Talmudists go wild with this passage, and do not interpret it literally….

Fazer grande fiesta is attested in medieval usage in a number of texts, always in the literal sense of ‘celebrated heartily’; this is the only example I have seen where it is used figuratively, even playfully.

When Rabbis give hypothetical examples to illustrate legal arguments involving two or more parties, they often use the convention of referring to them as Reuben and Simon (Fulano y Mengano in Spanish, maybe John and Jack in English). For example, “If Reuben owns an ox that gores a donkey belonging to Simon…” Arragel adapts this convention for his Castilian readers, replacing Reuben and Simon with Juan and Pedro (Shem Tov Ardutiel of Carrión also did this in his Proverbios morales). Genesis 42:01 tells how Jacob, suffering a famine in his homeland of Canaan, learns that there are stores of grain in Egypt: E vio Jacob que hauia çiuera en Egipto, etc. (and Jacob saw that there was grain in Egypt).

Obviously it is impossible to literally see all the way from Canaan to Egypt. Jewish commentators disagree as to how to best resolve this passage: some say that Jacob received a vision from God of the grain to be had in Egypt, so in a sense actually ‘saw’ it. Others say that Jacob literally saw people arriving from Egypt carrying sacks of grain. Arragel follows the interpretation of his countryman Abraham ibn Ezra (ca. 1080- ca. 1165), who says that in this case, ‘saw’ is metaphorical, in the same way that we say ‘I see’ for ‘I understand,’ framing this in terms of the perception science of his day:

por quanto syn dubda los çinco sentidos se juntan a vn lugar e ally se canbian el vno por el otro, que en veyendo la miel, la setençiamos dulçe, e en veyendo la fiel, la seteçiamos amarga, en caso que las non tastemos. En oyendo cantar a Pedro o a Juan, cognosçemoslos, avnque los non veamos estonçe, asy que con el sesto sentido que llaman el seso comun. (Paz y Meliá, Biblia de Alba: Genesis 154)

therefore, it is without doubt that the five senses come together in one place and there change places, so that in seeing honey, we think it sweet, and in seeing bile, we think it bitter, in the event that we do not actually taste it. When we hear Pedro or Juan singing, we know them, although we do not see them, and so it is with the sixth sense which we call common sense.

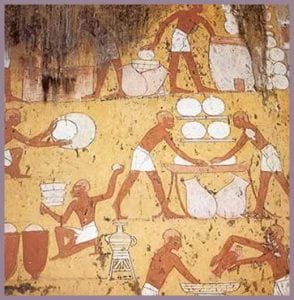

Using cows to trample wheat, from the Tomb of Menna, New Kingdom (wall painting) Egyptian 18th Dynasty (c.1567-1320 BC); Valley of the Nobles, Thebes, Egypt Source: wikipedia.org

Arragel’s use of vernacular language to interpret this passage doesn’t end there. To illustrate the argument of Rashi that Jacob literally saw grain in Egypt in a divinely-inspired (but not prophetic) vision, he gives the following aggadah (narrative explanation for a Biblical passage, meant to illustrate the sense of a passage but not authoritative in rabbinical argument):

otros dizen que vn rrio de Egipto a Chanaan yua, e Joseph, sintiendo que sus hermanos e padre en persecucion de pan serian, que echara por el rio pajas con espigas e que llegaron a Chanaan. (Paz y Meliá, Biblia de Alba: Genesis 129)

Others say that there was a river flowing from Egypt to Canaan, and that Joseph, knowing that his brothers and father would be looking for bread, threw straw with spikes into the river and that they arrived in Canaan.

It’s hard to know who the ‘others’ are to whom Arragel refers. Usually when he says this what follows is an interpretation not found in the commentaries of the Rabbis. This explanation is not found in any Biblical commentary; it is, however, found in the Coplas de Yosef, a 14th-century Castilian Jewish versification of the Joseph story:

Ya’aqob en esa tierra, allá donde estaba,

al río se fuera y las aguas miraba:

mucha paja viera que en el río andaba,

esta paja fuera que derramó Yosef

(Girón-Negrón and Minervini 141, st. 76)Jacob in that land [Canaan], where he dwelled,

went to the river and looked at the water:

he saw a lot of straw floating in the river,

it was straw that Joseph had scattered

Apparently, both the author of the Coplas de Yosef and Arragel were drawing on a local midrash (interpretation of a Biblical verse) that, while unattested in any prior Jewish commentary, has its source in a Castilian folk legend (later collected from a 20th century informant), explaining the origin of the name of the town, Tedeja (Girón-Negrón and Minervini 249 n 74–78). Here, the straw floating down the river announces the victory of Christian forces over their Muslim opponents that took place upriver from Tedeja:

Les echaron al río [las pajas] para ver la señal de lo que iban a hacer. Cuando llegaba el agua del río con las pajas es que habían ganao la batalla. Que ha habido una batalla ahí, sí, porque han salido muchos restos ahí en eso. La batalla fue en Tedeja. Y dijo el rey moro: ‘¡Ahí te dejo!’ y por eso se llama Tedeja (Pedrosa 94–95, no. 72)

They threw [the straw] in the river to see the sign of what they were about to do. When the river water with the straw arrived, they had won the battle. [Informant: Yes, there was a battle there, they found the remains of it. The battle was in Tedeja]. The Muslim king said: “I leave you [te dejo] there!” And that is why it’s named Tedeja.

In addition to material drawn from folktales, Arragel also makes good use of refranes (popular sayings; proverbs) in his explanations of Biblical passages. In Genesis 39, Potiphar’s wife unsuccessfully attempts to seduce Joseph, then tells Potifar that it was Joseph who tried to rape her. The rabbis distinguish between what she said and what she did, making the point that there is a big difference between saying something and actually doing it:

Fazer e dezir dos cosas son: asy que ella non auia de dezir saluo: esto e esto me dixo tu sieruo; pero dixo fizo, por lo qual raby Salamon [Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac of Troyes, aka Rashi] pone quel su marido estando con ella a lo que ya sabedes, e era tanto como que le dizia que se auia echado con ella. (Paz y Meliá, Biblia de Alba: Genesis 151)

Doing and saying are two different things: so, she should have said ‘your servant told me such-and-such; but instead she said ‘did,’ to which Rabbi Solomon [ben Isaac of Troyes, aka Rashi, ca. 1050-ca.1120] posits that as her husband was with her, which you already know, and it was as if she had told him that he had slept with her [by force].

Here Arragel deploys a refrán that is attested in Castilian works both Christian (the anonymous El Cavallero Zifar, ca. 1300) and Jewish (Shem Tov Ardutiel’s Proverbios morales, ca. 1330), as well as in the proverb collection by the Iñigo López de Mendoza, the Marquis of Santillana, Refranes que dizen las viejas tras el fuego (‘Refranes that old ladies tell around the fire’), which I mention just because the title is so cool.

Lost chicken poster, Photo: Mark Krynsky 2013. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/krynsky/10768955643/

My favorite of Arragel’s refranes rabínicos (‘Rabbinical proverbs’) is in his discussion of the rape of Dina by Prince Hamor of Shechem (Gen 34). The tale inspired not only a medieval Castilian ballad that continued to be sung by Sephardic Jews into the 20th century, but also a 17th-century play by the famous Lope de Vega. Jacob’s only daughter Dina sneaks out of the house to hear the singing of the local women in the street. Prince Hamor, son of the King of Shehem, sees her and sexually assaults her. The King offers to marry Dina to his son (ostensibly to legitimate the assault, to which Jacob agrees). However, her older brothers Reuben and Simon (the actual ones, not the legal fiction placeholders in the example above) aren’t having it. Having agreed to join the Israelite religion prior to marrying Dina, Prince Hamor and all his men were circumcised. The day after the circumcision, while they were still quite sore and indisposed, Reuben and Shimon take the opportunity to attack them, and avenge the attack on their sister by putting them all to the sword. You can see why this episode inspired so many narrative interpretations.

But we are here to talk about Arragel’s clever use of refranes. Rabbis tend to frame the tale as an admonition for women and girls to stay at home due to the danger that awaits them in the street. Arragel sums up his discussion of the passage saying:

Nota que la muger e la gallina por sallyr de casa se pierden, e ençerradas onestamente estar deuen. (Paz y Meliá, Biblia de Alba: Genesis 159)

Note that women and hens often get lost when they leave the house, and should rather remain chastely locked away [at home]

We find this refrán again in Santillana’s collection:

La muger [y] la gallina por andar se pierde[n] ayna. (Santillana 94, no. 374)

The woman and the hen, roaming about, often become lost.

Arragel’s work is greatly enriched by his use of vernacular language, turns of phrase, and popular sayings. He deftly uses the expressive resources of vernacular Castilian to enrich and enliven his unique work of Biblical commentary, making it more relevant to his medieval Castilian audiences. For modern readers, it is a unique window into how medieval Iberian Jews read Biblical and Rabbinical texts through the lens of contemporary language and culture.

Works cited

- Girón-Negrón, Luis M., and Laura Minervini. Las coplas de Yosef: entre la Biblia y el Midrash en la poesía judeoespañola. Gredos, 2006.

- Paz y Meliá, Antonio, editor. Biblia de Alba: Éxodo. 1899, http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000171563.

- —, editor. Biblia de Alba: Genesis. 1899.

- Pedrosa, José Manuel. Héroes, Santos, Moros y Brujas : Leyendas épicas, históricas y mágicas de la tradición oral de Burgos : Poética, comparatismo y etnotextos. Elías Rubio Marcos, 2001.

- Santillana, Iñigo López de Mendoza. Refranes que dizen las viejas tras el fuego. Edited by Hugo O. Bizzarri, Edition Reichenberger, 1995.