[This post includes material later revised and expanded in Double Diaspora in Sephardic Literature: Jewish Cultural Production before and after 1492 (Indiana University Press, 2015)]

Summary

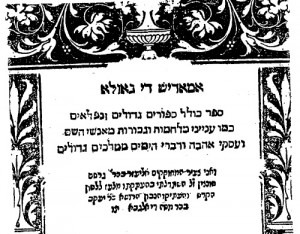

It was 1541 in Constantinople when Sephardic physician Jacob Algaba published his Hebrew translation of the first book of Spanish runaway bestseller Amadís de Gaula (1508). His translation of the endless adventures of the knight errant became the first novel written in the Hebrew language, and a literary example of Sephardic culture as the site of a symbolic struggle between the Spanish and Ottoman Empires.

In a way Algaba’s translation is exemplary of the complex relationship Sephardim had with the culture of the land from which they had been expelled in 1492. Part of the way in which the Sephardim expressed their ‘Spanishness’ was in mimicking the intellectual and cultural habits of Imperial Spain. They reenacted Spanish cultural imperialism by their imposition of Sephardic culture on the Jewish communities of the Ottoman Empire and by their adaptation of the Humanist rhetoric of Spanish historians and novelists. Just as the Spanish Amadís was imagined as a Christian hero of Spanish imperial designs, Algaba’s Sephardic Amadís was a sort of avatar of Sephardic supremacy within the Jewish world, and a response to the Sephardim’s alienation from Spain.

On the stage of the Mediterranean at the turn of the sixteenth century, the Sephardim are a sort of by-product of empire. Jettisoned from Spain, the Sephardim were free to rebrand ‘Spanishness’ to suit their own interests. They were hardly, after all, ambassadors of Spanish interests. But they were profoundly shaped by the cultural legacy of the land they had called home for over one thousand years by 1492. Though rejected by their home metropolis, they were still able to convert their Spanish identity into social currency in the host metropolis.

A Knight against the Turk

The chivalric novel Amadís de Gaula (1508) by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo was a smash hit and set the standard for popular fiction of the sixteenth century. Readers could not get enough of the (seemingly endless) exploits of the knight errant who protected the weak, battled dark knights, sorcerers, and dragons, all in the name of his beautiful damsel Oriana. Montalvo’s book, and its many, lucrative sequels, itself became a kind of popular literary monster that only Don Quijote could defeat, effectively parodying Amadís and his successors to death in 1605.

But Amadís was more than a fictional hero. Spanish readers imagined him (and in particular his son, Esplandían) as a kind of avatar of Spanish imperial desire, a knight in service to Spain first against the Muslim Kingdom of Granada, and then against the Turk (the Ottoman Empire). In casting these fictional knights errant as imperial heroes, Montalvo was simply participating in the Humanism of his times. Humanist writers working at the court of the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella actively promoted a program of imperial imagery that painted Spain as a new Rome, mixing language and imagery from the Latin writings of Imperial Rome with specifically Iberian and Catholic elements. The result was a narrative in which the Spanish crown was a renewal of the Holy Roman Empire, itself a renewal of Classical Rome (Tate, Ensayos 292). In the introduction to the first Amadís, Montalvo wonders aloud how the writers of Classical Rome would have been inspired to new heights had they witnessed the glorious campaigns of King Ferdinand in Granada:

¡what flowers, what roses might they have planted on its occasion, as concerns the bravery of the knights in the battles, skirmishes, and dangerous duels and all the other cases of confrontations and travails that were performed in the course of that war, as well as of the compelling speeches made by the great King to his nobles gathered in the royal campaign tents, the obedient replies made by them, and above all, the great praises, the lofty admirations that he deserves for having taken on and accomplished such a Catholic task!

(Rodríguez Montalvo, Amadís 219-220, translation mine).

Once the threat of Muslim Granada had been conquered by Ferdinand and Isabel in 1492, it was a logical next step to look toward Istanbul. The Ottoman Turks had, after all, conquered Constantinople in the not-so-distant past, and the loss of Christian Constantinople was, during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, still a fresh wound. Diego Enríquez del Castillo (ca. 1500), wrote that “the pain of the loss of Constantinople, that the Turk had conquered, was very recent in the hearts of all.” (Crónica 156). Ever since the Ottoman sack of Otranto, Italy in 1481, Spanish (and particularly Aragonese) writers were preoccupied by the possibility of a Turkish invasion of the Peninsula (Giráldez, Sergas 24). While an Ottoman invasion of Spain was probably not in the offing, such fears were similar to US fears of a Soviet invasion 1960s following the Cuban Revolution and famously parodied in the 1966 film The Russians are Coming, The Russians are Coming. The cult of Amadís and his successors and their iconic (if anachronistic) status as Christian heroes of imaginary conquests in the Mediterranean East were an understandable, if irrational, reaction.

Don Quijote’s Dream Team: Knights Errant vs the Turk

Mehmet enters Constantinople (1454) by Fausto Zonaro (1854-1929)

Amadís finally met his match in Don Quijote, who parodied the knight errant protagonists of the Spanish chivalric novel beyond any hope of redemption. Interestingly, Cervantes also zeroed in on the tendency of fans of chivalric fiction to conflate the exploits of their heroes with current events. In this scene, Alonso Quijano (aka Don Quijote) suggests a simple solution for King Philip II’s ‘Ottoman Problem’: round up all the Spanish knights errant and send them to fight the Turk:

there might be one among them who could, by himself, destroy all the power of the Turk…. [if] the famous Don Belianís were alive today, or any one of the countless descendants of Amadís of Gaul! If any of them were here today and confronted the Turk, it would not be to his advantage!’ (trans. Grossman 461)

The effect is similar to a movie in which the sci-fi crazed protagonist suggests sending Luke Skywalker to battle Al-Qaeda. The English translator of Sergas de Esplandían (Montalvo’s sequel to Amadís) made a similar observation, calling Luke Skywalker “a kind of Esplandían redividus” (Little, “Introduction” 21).

What does a Sephardic Amadís look like? And what might a Hebrew Amadís champion, if not the Spanish conquest of Ottoman Istanbul where Jacob Algaba translated the exploits of the Ur-Knight Errant into Hebrew a generation after Montalvo described Amadís’ deeds as worthy to be celebrated by the pens of Imperial chroniclers? In order to answer this, we need to take a look at the ways in which Sephardic intellectuals retooled and adapted the intellectual habits of the Spain they had left behind.

‘Doing Spanish’: Sephardic Humanism and Cultural Imperialism

Upon their arrival in Ottoman lands, the Sephardim proceeded to dominate the Romaniote (Greek-speaking) and other Jewish communities. They were bearers of a prestigious European cultural legacy, and many of them were highly skilled in areas valued by the Ottoman Sultans: finance, administration, diplomacy, and the like. In addition the Sephardim had access to tremendous social capital in the form of international, even global trade and diplomatic networks. Contemporary sources bear out this characterization of the Sephardim as the socially and culturally dominant group within Ottoman Jewry, imposing their liturgy, rabbinic jurisprudence, cuisine, language, and social customs on the wider community. Writing in 1509, Rabbi Moses Aroquis of Salonika bears witness to this phenomenon:

It is well known that the Sephardim and their scholars in this empire, together with the other communities that have joined them, make up the majority, may the lord be praised. To them alone the land was given, and they are its glory and its splendor and its magnificence, enlightening the land and its inhabitants. Who deserves to order them about? All these places too should be considered as ours, and it is fitting that the small number of early inhabitants of the empire observe all our religious customs… (cited in Hacker, “Sephardim” 111)

This Sephardic cultural imperialism is one way in which the Sephardim expressed their ‘Spanishness,’ in carrying out a version of the Spanish cultural imperialism that characterized the late fifteenth century. Just as Spain colonized the Canary Islands, the New World, and bits of North Africa, the Sephardim did likewise in their new territories, the Jewish communities of the Ottoman Empire.

This imperialism, like the Spanish, also had its attendant historiography, its intellectual culture: a Sephardic Humanism. The historian Solomon ibn Verga, writing in Hebrew in the mid-sixteenth century, borrowed liberally from Spanish sources and like his Christian historian counterparts, legitimized the current political order by linking it to the regimes of Classical Antiquity. In his history of expulsions and persecutions he writes like a Humanist, substituting both authors of Hebrew antiquity (Bible, Rabbis) for Latin and Greek authors favored by Christian humanists, but he also draws on Classical and medieval Iberian authors, lending his prose of more sophisticated, cosmopolitan tone. (Gutwirth, “Expulsion” 149-150). He cites Josephus frequently, creating a Jewish humanist precedent in the Roman author who plays Virgil to his Dante.

Amadís in the Sephardic context

What is the role of a Hebrew Amadís in this context? As with the case of Ibn Verga’s history book (Shevet Yehudah), the project of the Sephardic intellectual is twofold: on the one hand, they sought to legitimize their work by drawing on the prestige of Spanish Humanism; on the other, they reshaped this humanism into one that reflected the values of the community in a diasporic, transimperial context.

Algaba’s translation does not appear ex nihilo. Ottoman Sephardim were avid readers of Spanish editions of Amadís and other chivalric novels. In the early sixteenth century, Jerusalemite Rabbi Menahem di Lunzano chastised his community (in verse) for reading Amadís and Palmerín [de Olivia, 1511] on Shabbat (the Sabbath), when they should have been reading religious books (Di Lunzano, Shete Yadot f. 135v). There was also a robust tradition of ballads sung in Sephardic communities about heroes named Don Amadí (or sometimes Amalví or other variants). Many of these songs had nothing to do whatsoever with the stories found in Montalvo’s book; Amadís had simply come to mean ‘hero’ in the popular Sephardic imagination. (Armistead and Silverman, “Amadís” 29-30)

Montalvo’s original Amadís had to pass muster with the Catholic censors and with the chivalric imaginary of the Spain of the Catholic Monarchs. Algaba, while giving voice to the Sephardic love for their vernacular culture, is free of these limits. He based his translation not from Montalvo’s 1508 edition, but from an earlier manuscript version whose Amadís was earthier, wilier, less courtly and less likely to make it into print in Spain in 1508. Algaba’s Amadís plays dirty when nessary, and the characters in Algaba’s version tell it like it is. In one example, Algaba includes an episode omitted by Montalvo where Amadís tricks his opponent into looking away in order to hit him: He asks the knight ‘to whom does that beautiful maiden behind you belong?’ When the knight looks away, Amadís sticks him in the groin with his lance, spilling his guts (Piccus, “Corrections” 187-88). In another example, Montalvo omits a reference to a character farting that is included by Algaba (Piccus, “Corrections” 201). These are scenes that do not pass muster with the chivalric imaginary of the Spain of the Catholic Monarchs.

The Hebrew Amadís, therefore, is at once celebratory of and resistant to Montalvo’s Amadís. The culture of Montalvo’s Amadís, with its exaggerated religious rhetoric and rarefied standards of courtliness, has rejected Algaba (who was born in Spain), and Algaba is happy to return the favor, refashioning Amadís as a Sephardic hero, one who springs from Iberian tradition but who is free of the restraints of official Spanish culture as propagated by the courts and controlled by the censors of the Catholic Monarchs.

Works cited

- Armistead, S. G. “Amadís de Gaula en la literatura oral de los sefardíes.” La pluma es lengua del alma: Ensayos en honor del E. Michael Gerli. Ed. José Manuel Hidalgo. Newark, DE: Juan de la Cuesta Hispanic Monographs, 2011. 27-32.

- Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel. Don Quixote. Trans. Edith Grossman. New York: Ecco, 2003.

- Enríquez del Castillo, Diego. Crónica de Enrique IV de Diego Enríquez del Castillo. Ed. Aureliano Sánchez Martín. Valladolid: Secretariado de Publicaciones Universidad de Valldolid, 1994.

- Giráldez, Susan. Las sergas de Esplandián y la España de los Reyes Católicos. New York: Peter Lang, 2003.

- Gutwirth, Eleazar. “The Expulsion from Spain and Jewish Historiography.” Jewish History: Essays in Honour of Chimen Abramsky. London: Peter Halban, 1988. 141-161.

- Hacker, Joseph. “The Sephardim in the Ottoman Empire in the Sixteenth Century.” The Sephardi Legacy. Vol. 2. 2 vols. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1992. 108-133.

- Little, William. “Introduction.” The Labors of the Very Brave Knight Esplandían. Trans. William Little. Binghamton, N.Y.: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1992. 1-61.

- Lunzano, Menahem di. Shete yadot. Jerusalem: [s.n], 1969.

- Piccus, Jules. “Corrections, Suppressions, and Changes in Montalvo’s Amadís, Book I.” Textures and Meaning: Thirty Years of Judaic Studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Ed. Leonard Ehrlich et al. Amherst: Department of Judaic and Near Eastern Studies, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2004. 179-211.

- Rodríguez de Montalvo, Garci. Amadís de Gaula. Madrid: Cátedra, 1987.

- —. Sergas de Esplandían. Ed. Carlos Sainz de la Maza. Madrid: Castalia, 2003.

- Tate, Robert Brian. Ensayos sobre la historiografía peninsular del siglo XV. Madrid: Gredos, 1970.

This post was adapted from “Reading Amadís in Constantinople: the Sephardic as imperial abject,” a paper I gave at the 2011 UC Mediterranean Research Project Fall Workshop: “Mediterranean Empires” on 29 October 2011 at UCLA. [Workshop program] Thanks to the Seminar organizers for their hospitality and support.