2013 participants on an excursion to Madrid

In 2013 I served as visiting faculty for a now-defunct study abroad program in Oviedo, Spain. My family and I spent six months living, working, and attending school in Asturias under the auspices of GEO (Global Engagement Oregon), then known as AHA. It was a great experience, so much so that when the program was discontinued, I decided to develop a new, faculty-led summer program at GEO’s Oviedo Center for students at the University of Oregon and GEO partner universities. I led a group of Spanish majors in August 2014, and again in 2015. I taught two 4-credit courses in the month of August, catering to Spanish majors looking to complete upper-level coursework. I redesigned the program in August 2019, this time with a group of (mostly) Spanish minors whose majors occupied most of their time during the academic year but who were excited at the prospect of satisfying their minor requirements and experiencing a linguistic and cultural immersion. The program was a success. It enrolled fully, and students reported a positive experience.

I’d planned to repeat the program in Summer 2020, and so spent Fall 2019 and Winter 2020 recruiting furiously. It paid off, and by March enrollment was full.

In anticipation, I’d prepared a new course reader that was focused on content related to the program site visits. This way, students would read about a site, visit it, and complete assignments meant to integrate the readings and their experiences on site. I’d had some success with this approach in past iterations of the program, but this time I really focused on making the readings directly relevant to the excursions and integrating medieval readings with modern readings on related cultural and historical issues.

The challenge in preparing these materials is that it is difficult to find texts on these topics that are linguistically appropriate to advanced intermediate learners of Spanish. Much of what is available relative to, for example, the region’s architecture, is written for specialists, or for adult native speakers of Spanish. As a result, the reader is a bricolage of sections of wikipedia pages, newspaper articles, books, and other sources heavily edited and glossed for non-native student readers.

Then COVID happened. The program was canceled, and the reader, which I’d spent so many hours preparing, was suddenly useless, at least for 2020. Hopefully I’ll use it in 2022.

Then COVID happened. The program was canceled, and the reader, which I’d spent so many hours preparing, was suddenly useless, at least for 2020. Hopefully I’ll use it in 2022.

I’d like to share it with you, in the hopes that it is useful to you, or perhaps it will inspire others to do likewise. The texts are all under an open license, Creative Commons BY-SA-NC, meaning that anyone is free to use, duplicate, modify, and publish for non-commercial purposes.

I also added a ‘union made’ badge to the materials, to let readers know that the author enjoyed union protections, and that union membership strengthens academic freedoms and provides the kind of stable employment conditions that create favorable conditions for the creation of Open Educational Resources.

What follows is a guided tour of the reader’s units, to give you an idea of how they support site-specific student learning. You can start with the table of contents, that also has a link to the course syllabus.

The first site visit is the Roman Baths in Gijón, so I prepared a selection of Strabo’s Geography describing Lusitania, to help students see that Asturias was part of the Roman Empire and what that meant for Asturians at the time, as well as for current-day Asturians’ understanding of their own regional history. I paired this with an article about a nearby excavation of a Roman-era site, to help then make the connections between past and present.

2019 participants visit Covadonga

The next excursion was to the Santa Cueva de Covadonga, (and to the Iglesia de Santa Cruz in nearby Cangas de Onís) where according to legend took place a battle between Umayyad troops and a band of fighters led by Pelayo, a local warlord (the Arabic account, interestingly, says that no such battle occurred). This battle has become part of Spain’s foundational narrative, much like the “Shot heard ’round the world” from the US Revolutionary War. The legend is included in the 10th-century chronicle of Asturian King Alfonso III. I paired this with a news article on how the president of Spain’s right-wing Partido Popular has used Pelayo as a symbol of modern nationalism.

The Chronicle of Alfonso III also contains a section on the construction of some of the area’s most well-known pre-romanesque monuments. We visited the interpretive center dedicated to Asturian pre-romanesque architecture (Centro de Recepción e Interpretación del Prerrománico Asturiano). In preparation for this visit we read the corresponding section of Alfonso III’s chronicle, together with a chapter I adapted from a book on Asturian pre-romanesque architecture. I included a section on architectural terminology to give them some vocabulary to discuss the monuments.

2019 participants on the Camino Primitivo

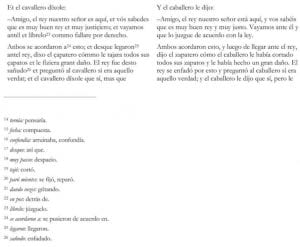

Next we were to hike a section of the Camino Primitivo (the older route of the Camino de Santiago connecting Oviedo to Santiago via Lugo) ending up in the town of Grado, so we read Berceo’s Milagro of the Pilgrim to give them some sense of the very important culture of pilgrimage in the region and its role in the development of literature in the vernacular (here medieval Castilian). I added a short piece from ABC news featuring a US soldier en route to Afghanistan showing a tattoo of the Virgin of Guadalupe he’d gotten for protection (just as Berceo’s pilgrim called on the Virgin for protection).

After that we were scheduled to see the relics in the Cámara Santa of the Cathedral of Oviedo, so we read the Leyenda de San Toribio that explains their putative origin and how they ended up in Asturias.

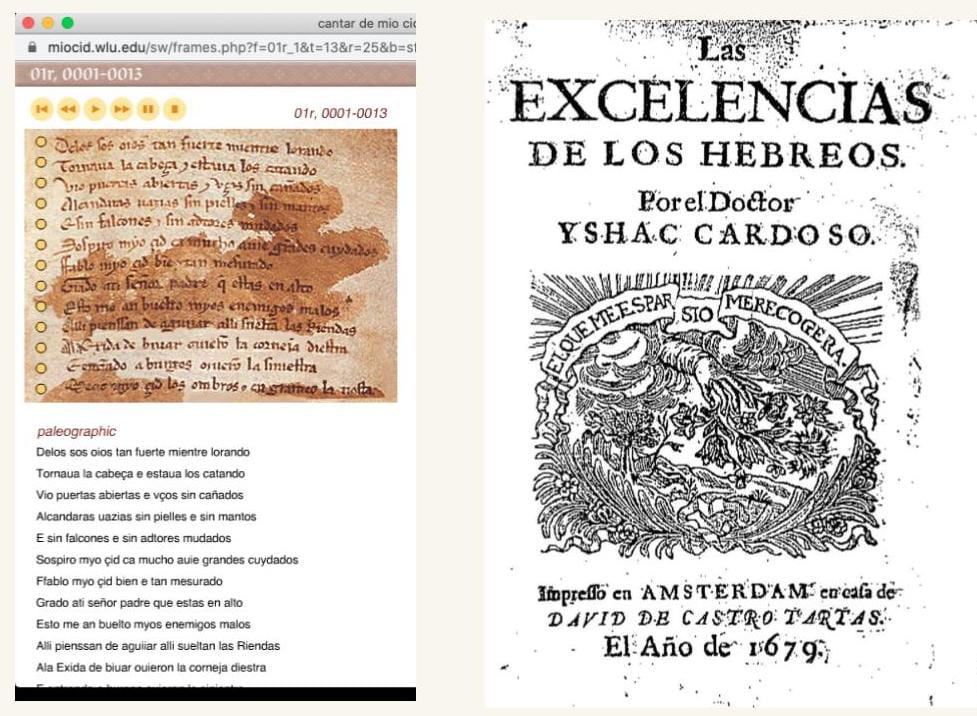

2019 participants at the synagogue

Then we were to visit the local synagogue and do a unit on Jewish history, so we read an article on a genealogical study of Asturias (according to the study the region with the highest Sephardic genetic profile), and a poem by medieval Hispano-Hebrew poet Judah Halevi translated into modern Spanish.In honor of our planned visit to the Asturian collection of the Biblioteca de Asturias we read about officiality and the 17th c. debate between Oviedo and Mérida (written in Asturian). We also planned for Ethnographer and author Alberto Álvarez Peña to give a presentation on the Asturian language (as he had in past iterations of the program).

The visit to the local mosque was paired with a news article on Spain’s first online Arabic-language newspaper, a unit on al-Andalus and selections from Andalusi poets Wallada and Ibn Zaydun translated into modern Spanish.

Finally, Aljamiado expert Pablo Rozas Candás was to give a talk on Moriscos and aljamiado literature so here’s the unit on Moriscos and Doncella Arcayona, accompanied by a news article on a 2002 petition to the Spanish government by a Moroccan historian advocating for a right of return for descendants of Muslims expelled from Spain in the 17th century.

This post began life as a twitter thread that you can read here.

Many thanks to GEO Program Coordinator Liz Abbasi, GEO Oviedo Site Director Silvia Pérez, and the students who participated in the 2019 program.

Anyone who has taught panoramic survey courses of literature knows the frustration of working with published textbooks. I’ve argued both sides of the question in my blog:

Anyone who has taught panoramic survey courses of literature knows the frustration of working with published textbooks. I’ve argued both sides of the question in my blog: